Whisky Diaries: reconsidering the word ‘terroir’

barley, language and climate change, Agnès Varda and some tasting notes; a discovery journey

The first time I had whisky, I was in Dublin. I had come to spend the Easter weekend at a friend of a friend’s flat, a few years before the pandemic. I remember drinking a lager from the bottle while listening to live music along the canal and that we ate tacos at a food market in a parking lot. We visited the reconstruction of Francis Bacon’s studio at the Hugh Lane Gallery, and we headed to the pub. I was with two girlfriends. We mumbled until we felt brave enough to ask the bartender for a glass of whisky. ‘Which whiskey would you like?’ they must have asked. I have no idea what we drank; I don’t remember liking it either.

Or it could have been before that, on my way to a nightclub in Paris, when I had mixed some Jack Daniel’s and Coke inside a recycled water bottle.

Truth be told, I don’t know much about whisky. But I know that I like it when my lips tingle and to feel the back of my throat warm and tight. I like it mellow, not peated. A touch of vanilla but not as sweet as honey, testing before it hugs me.

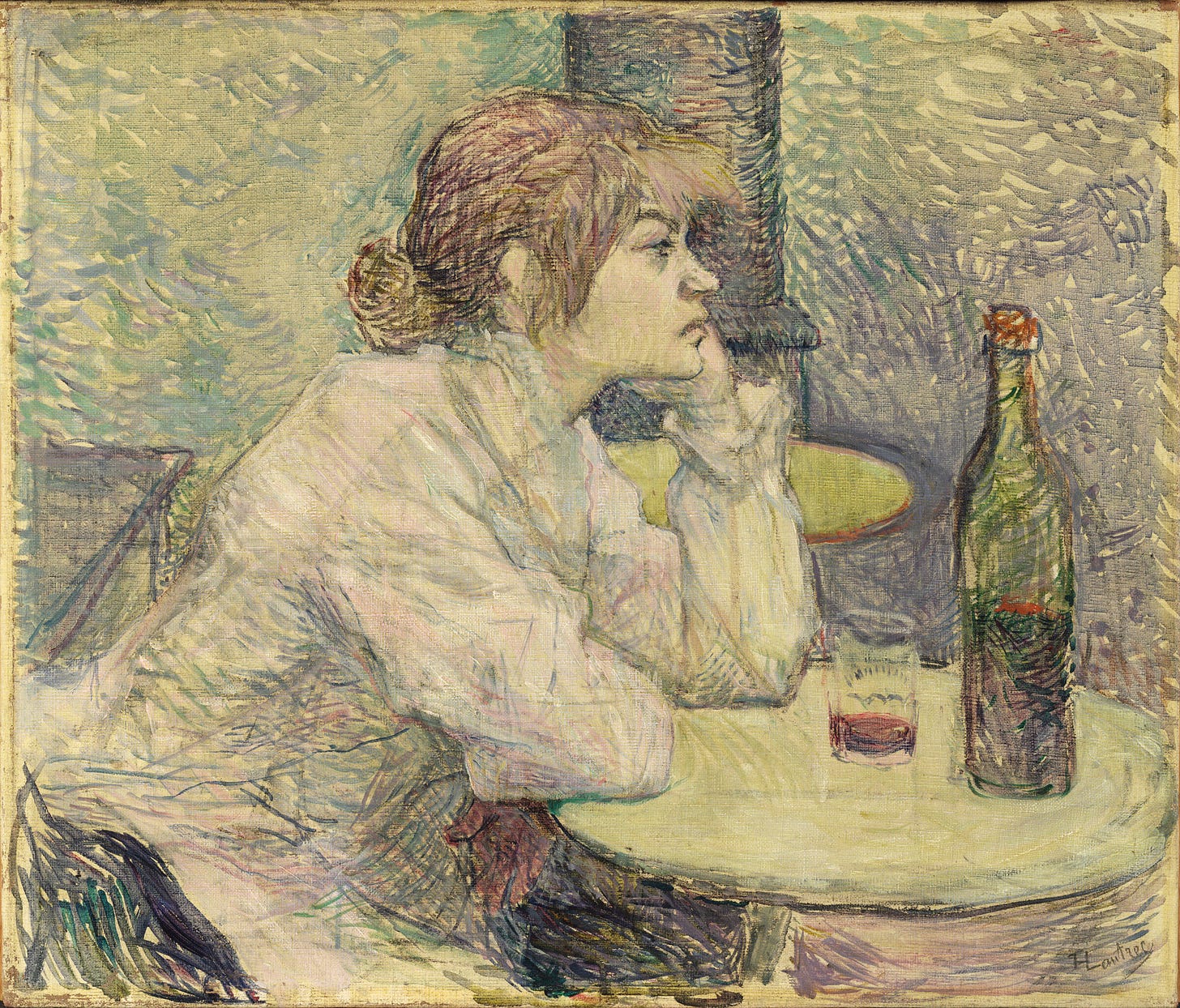

I enjoy a drink and I’m interested in the history behind spirits. Whether they are personal or corporate stories, accounts about abstention or addiction, they always say something about the socio-cultural and political contexts, the geography and the environment of a place and/or a person. The long history about how alcohol has been policed and taxed by institutions also shows that, to research drinks, is to collect stories and to expose facts about past connections and disconnections between people and governments.

Since moving to Scotland, I have had the opportunity to visit numerous distilleries and to meet generous and knowledgeable people who work in the industry. Whisky is made of three ingredients: barley, water and yeast. Then, there are few rules to obey to prepare and sell single malt Scotch whisky specifically, which are useful to keep in mind before I dive in: it must be made from malted barley; it must be distilled in pot stills and at a single distillery; it must be matured for at least three years. In addition to that, there are the variations each distillery and their master distillers will bring to those ground rules, such as where the water comes from, to use a wood or a steel washback, the size and shape of the stills and the types of casks used for the maturation of the whisky. Each decision will impact the individual product’s identity as part of the single malt Scotch whiskies offering; from three ingredients, the combinations of taste are almost infinite.

Then, over Easter this year, I travelled to Islay.

Islay is the southernmost of the Inner Hebrides islands and is renowned for its production of whisky, which goes back to the 1300s when Irish monks are said to have brought distillation to the island. (I wrote about Islay here.) It was at the local Bruichladdich distillery that I heard someone use the term ‘terroir’ to speak about whisky production for the first time. The word ‘terroir’ is, according to the Cambridge dictionary, ‘the particular environment in which the grapes for the wine were grown, which gives the wine a special character.’ However, the original meaning of the French word has narrowed through the translation process.

Terroir encapsulates the influence of a region – from its environment and soil composition to its farming methods – over the growth and culture of the local crops and the food it produces. I wouldn’t use the word without mentioning the character of a land: it has more to say about the source and the journey of the tradition than it does about how the end-product taste.

Returning to Bruichladdich, the word terroir was used in relation to an on-going project they initiated in 2005, jointly with the University of the Highlands and the Island’s Agonomy Institute, to reintroduce Bere barley to produce whisky. From that came out their ‘Bere Barley 2013’. Bere is a six-row barley and Britain’s oldest and continuously cultivated cereal, since the neolithic times, yet it had almost disappeared. It used to be a staple of Scotland’s distillers, until modern varieties of barley were favoured for their consistent flavour and overall yield. Today, Bere is mainly grown on Orkney and while Bruichladdich have a 100% Islay whisky, made with local Bere barley, most of the production is outsourced up in Orkney. When we asked why not prioritising Islay-based farms, we were told that the island’s weather is so wet and changeable that the barley they had tested, from different growers across the island, grew unpredictably and made the final spirit too unstable in taste for commercial use.

On the one hand, there is a clash with the history of the word terroir, in that the barley isn’t grown on Islay, where the whisky is produced. It’s worth noting here that I’m not judging Bruichladdich’s decision as I don’t have enough data and expertise to do that. Most distilleries I have visited also outsource the production of barley for commercial standards and quality control’s sake. As such, while the making of the drink (incl. distilling and maturation methods) is local to the distillery, a whisky isn’t wholly dependent on the regional land where it matures. On the other hand, thinking about what could any terroirs look like tomorrow, when weather patterns thus soil types are changing radically, how meaningful can a rigid definition of the concept of terroir be?

‘If we opened people up, we’d find landscapes. If we opened me, we’d find beaches.’

— Agnès Varda, from her autoportrait film The Beaches of Agnès (2008)

I also like to think that if you opened me, you’d find a pebbly beach. That if I were a whisky, the liquid would be peated with a salty undertone – but that is an autofiction of my own. I quote Agnès Varda, and a part of me is frustrated at myself for writing about alcohol, as a woman when the industry is still predominantly male, from the angle of personal experience. Until I realised that I had forced this expectation on myself not to write about the topic; I was afraid. But here is something else I believe: the land, like our bodies, grows old through the irrevocable passage of time. We break and we adapt, and we rot or thrive.

In that, through the bones that bear witness for our natures, the word terroir appears as a variable – something to be searching for, time and again. A framework for both preserving, where ecosystems need protection, and an activist arc to bow when human and wildlife welfares are being extinct by profits-driven oil and soil exploitations as well as mass-consumption politics that only serve few people. In November 2023, Oxfam reported that ‘the richest 1 percent of the world’s population produced as much carbon pollution in 2019 than the five billion people who made up the poorest two-thirds of humanity.’

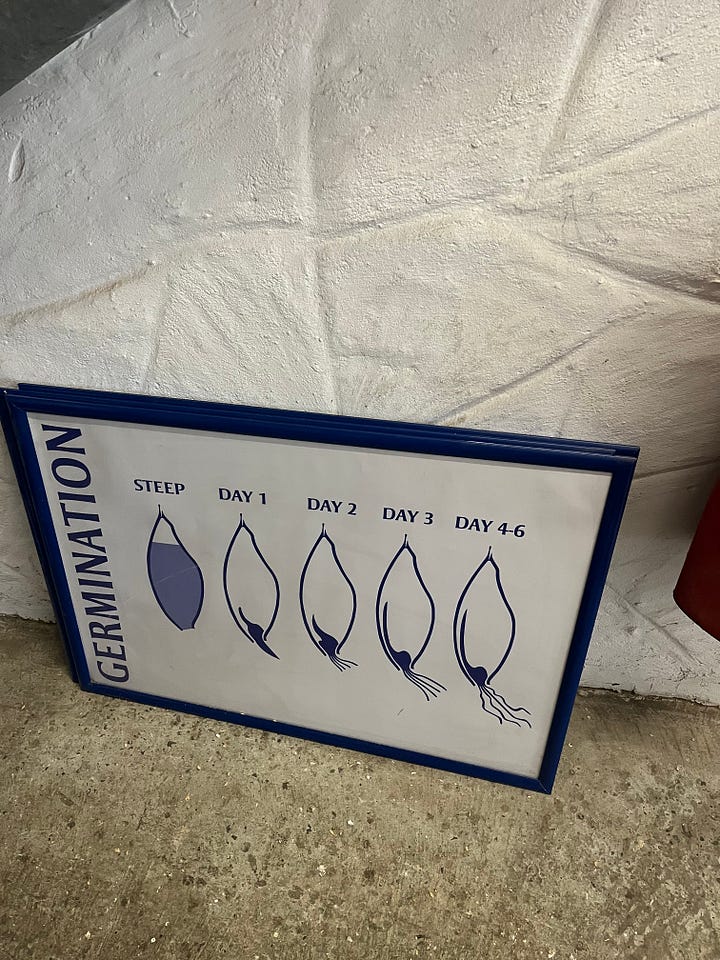

Circling back to the whisky production and the barley, I also visited Islay’s farm and distillery Kilchoman. While they outsource most of the barley they use to make whisky, Kilchoman owns one of seven traditional malting floors still operating in Scotland (see picture above). For approximately five days, the barley is spread over the ground in that room, where it’s monitored by the staff every two hours. Human touch and scent as well as the climate and daylight, regulated by the simple opening of windows, are used to mature the barley. When it’s too cold, the barley is piled to nest the cereal and to keep it warm or, if the grains are too moist, the barley is spread thinly over the ground. As a result, Kilchoman can sell a bottle that is marketed as 100% Islay whisky.

I’m interested in the effect that bottle had on us consumers. As a tourist who had come to visit this island off the west coast of Scotland, I wanted to buy that bottle – to bring a piece of Islay home to Glasgow with me – and I stood in the shop holding it up my nose to read the label. A man walked past me and said, with an American accent: ‘I bought that one too, it’s good.’ I’m not saying this is wrong. If you show me a bottle of Château Margaux, you’ll see me smile because even if it’s not a wine I drink, I was named after it and I think that it tastes like my mother’s garden. Of course the heritage of a place matters – as it should – but my point is that this identity, like the movements and bodies of people, can’t be controlled or limited by set expectations. Energies must flow.

Keeping up with the wine for comparison sake, as much as the idea that a Château Margaux could be made with the original grapes being grown elsewhere than the Médoc region and still be called Château Margaux puzzle me, the thought brings another, urgent question to mind: how long until the grapes down south will be sunburnt? As ecosystems collapse, we must review how we define authenticity. According to the UNHCR, there were nearly 32 million human displacements caused by weather-related hazards in 2022, which is more than the entire population of Australia and represents a 41% increase compared to 2008 levels. Health and safety measures for those who work the land under unprecedented heatwaves must be addressed urgently. The list of how unprepared we are for the future goes on, and we can’t have any conversations about climate change and land justice without rethinking our personal and societal relationships with the land – they are two interlinked bodies.

This is the story behind today’s newsletter: how I started to rethink what the idea of ‘the terroir’ implies, after I had grown out of love with the word terroir. I found it archaic and that it entertained an unreal and privileged view about the soil. A power play to crown one way or one region as superior from another, and a term used to justify colonial politics when it came to agrarian laws and land ownership. It’s the whisky industry that has made me consider using the word again. At distilleries, I have had challenging and energising conversations about adapting to survive. The current demand for Scottish whisky may be at one of the highest points in history and new distilleries are opening at a fast rate, but it wasn’t always the case. Many had to close – I mentioned stories about Arran and Campbeltown before – and the production is having to adapt to new economical and natural climates. For one, whisky making requires a huge amount of water and water accessibility is about to be one of our biggest issues as a civilisation. There are a lot of conversations about sustainability happening in and around distilleries nowadays and I don’t want to rush that point for the sake of ticking the box, but I would like to follow-up on this at a later stage. Inter-industries cooperation is key too, and to discuss whisky is to talk about the farms that operate around the distillery and where the casks come from. However young or old a distillery is, its maintenance is a juggling act between carrying on and renewing the traditional craft of whisky making – as the word terroir should be to be inclusive of our planet’s landscapes diversity.

We didn’t buy a bottle of 100% Islay Kilchoman whisky but the Loch Gorm edition. It has a sherry cask finish and, this season, the small terroir of my body likes that best – thicker on the tongue, slower to open up at the back of my mouth.

Margaux

PS. If you enjoy this newsletter, feel free to forward it to a friend, or two.

further reading:

More about Bruichladdich distillery here. They produce some of my favourite whiskies, including the Bere Barley line referenced in this newsletter. Their Port Charlotte is about how much I can do with peated whiskies.

Read more about Kilchoman farm and distillery at their website.

Arran 10yo is the whisky that helped me to build confidence around the spirit. It’s smooth and fresh – and it has the prettiest label, if you ask me.

Where to begin with Agnès Varda and BFI Player links: https://www.bfi.org.uk/features/where-begin-with-agnes-varda

My second novel, Breaststrokes, is publishing in a few weeks, on 9th May, and you can pre-order a copy at your favourite bookshop or at one of the links listed here. Pre-orders mean the world to authors with small platforms like me, so thank you.

#19: from Islay

I travelled to Islay by sea, and I arrived wet. Everything I had brought with me was still damp from the storm that had hit the mainland the day before, when I thought I could hike the Cobbler, but Mother Nature said: ‘No, no Margaux, you can’t see a thing.’ Ludo was standing next to me, then he vanished in the fog. The air was denser than velvet, and I…

Thank you for reading. The Onion Papers is a reader-supported publication. If you enjoy my work, you can support what I do by upgrading to a paid subscription. You’ll get access to the full archive and Monday annotated recipes. It costs £4 per month, or £40 a year, and you can unsubscribe at any time. No pressure: I’m happy you’re here either way.

*If you’d like a subscription, but now isn’t a good time, drop me a line and I’ll comp one for you. I only need your email address; no questions asked.

I loved reading this!

Is the water used not a basic part of the terroir? The peaty, smoky taste comes from the peat the water runs through. Only Islay whisky has that real peaty tang. Having said that, I hate to say this, I love the smell - I am happy just sniffing the cork - but I really don't like the taste of any whisky although I absolutely love Islay itself.