At Various Ends of Our World

entries from the Kintyre peninsula, Scotland; recipe for a fish pie/tarte

I.

The light alerted me. Brighter than anywhere else I had been, regardless of how windy, rainy or sunny the weather was; I squinted my eyes, searching for the seals the woman behind the bar in town had mentioned, but I kept confusing rocks for the animal’s head. However hard I craved a sight of wildlife, I was blinded by the luminosity. The sun streams steamed above the choppy sea and the shoreline was interrupted by white-sand beaches, the water the colour of duck feathers, and the geological evolution had scarred the cliff above it. Rocks cracked open for the bones of this land on which I was walking for the first time. Birds hovered before they took a plunge between two waves; at this end of the world, my intuitions were unleashed and corrupted, sensual and desperate, unreliable, they tasted delicious.

A falcon was perched on a fence. The bird of prey posed for long enough so I could take a picture. I was humbled: I had joined its end of the world. I had come here to hike around the Kintyre peninsula, and I hadn’t anticipated to feel so small. Not diminishingly small – not tiny with my portions and my opinions the way I was taught to be good when I was a girl – but there I felt small enough to recognise great forces before me.

‘Walking thus, hour after hour, the senses keyed, one walks the flesh transparent. But no metaphor, transparent, or light as air, is adequate. The body is not made negligible, but paramount. Flesh is not annihilated but fulfilled. One is not bodiless, but essential body.’

— The Living Mountain by Nan Shepherd

II.

With the low tide, a shingle causeway to Island Davaar emerged. The high tide was due at 23:02, so I set forth, mussel shells crackling under the sole of my feet, my legs helpless against wind gusts. Puddles of water smelt stronger than the sea on each side of the pathway; pebbles had a sickish tone, as green as the promise of grass at the end of the sandy road. So I kept walking, placing one foot after the other, because I was told that waving at sheep brings good fortune and I could use a hug, here on the edge of a tidal island. There was no other land or human at sight, yet I collected enough old plastic bottles to fill a bin.

I ventured around the island anti-clockwise.

Until a signpost.

Inside the cave above it, I was faced with a life size painting of the crucifixion. There were rocks, engraved with names at its feet, as well as candles, some consumed and others waxy. Later, back on the land, I would read online that the painting was made in 1887 by local artist Archibald MacKinnon, after he had a vision that suggested him to do so. The painting was interpreted as a sign of God and, it was reported, that when people discovered MacKinnon was in fact the author, he was exiled. I was reminded of ‘In Jerusalem’, a poem by Palestinian author Mahmoud Darwish. I wondered what God would be governing at the end of my own world – and I wondered if I would be judged for the doings of the said God and government.

‘In Jerusalem, and I mean within the ancient walls,

I walk from one epoch to another without a memory

to guide me. The prophets over there are sharing

the history of the holy . . . ascending to heaven

and returning less discouraged and melancholy, because love

and peace are holy and are coming to town.’

— ‘In Jerusalem’ by Mahmoud Darwish

For as long as tides will oscillate, there can’t be a set ending for the world.

III.

At the south tip of the peninsula, there is a cemetery. It’s small and well-kept. At the front, on the side of the road, someone has placed some stones with flowers painted on them. ‘Please take one :)’ is written on a piece of cardboard, so I tidied a pretty stone inside one of my backpack’s pockets. I keep it there, still, together with the chestnut I had picked months ago, in a woodland, to protect me from winter colds.

‘In the middle of the journey of our life I came to myself within a dark wood where the straight way was lost. Ah, how hard a thing it is to tell what a wild, and rough, and stubborn wood this was, which in my thought renews the fear!’

— The Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri

Southerner than where I had thought to be the edge of the coastline, a lighthouse. I don’t walk down the hill towards the building. I’m scared of the brutality of the wind and that I might never come back if I go; the gale lifts my body, I still can’t spot a seal, and only then I dare think of a castle.

‘If you have built castles in the air, your work need not be lost; that is where they should be. Now put the foundations under them.’

— Walden by Henry David Thoreau

IV.

At the pub, two teenagers and an elderly man control the jukebox. They chuckle as they share stories about past night-outs in Glasgow. I listen even if they don’t speak to me. L. smiles at the music in disbelief.

Before that end of the world, there was another world. Campbeltown used to be the whisky capital of the world with more than thirty distilleries in town, until the economy and repercussions from the Prohibition in the United States drew a line over profits and most distilleries, which were usually owned by farmers then, had to cease business. Today there are three distilleries remaining and their activity and quality still account for one of Scotland’s official whisky regions (alongside Islay, Speyside, Highlands and the Lowlands). I visited Glengyle’s Kilkerran, which first operated from 1872 to 1925, and was established as the outcome of a brother’s quarrel. As it happened with family stories, there is more than one side to it, so I invite you to read more about it at the distillery website. After numerous failed attempts, the Mitchell’s Glengyle Distillery reopened in 2004, having been bought by its bigger sister (located across the road): the Springbank Distillery. The Kilkerran distillery is far more than a revenge-seeking enterprise nowadays; the production is independent and, while the distillery only manufactures during four months per year, the entire whisky-making process, from growing the barley to numbering the bottles for sale, happens on site.

(On Monday, I shared a recipe for madeleines that pair well with a dram of Kilkerran 12yo.)

V.

I find a sea urchin skeleton, the empty shell frail like porcelain. A woman walks her cat on a leash. I’m thirsty here; chapped lip, arms open towards the west coast, facing Atlantic outbreaks. Two men, dressed in wetsuits, cross the road.

The blue hour lands a hopeful blanket over town. Then, a fish pie for dinner.

A recipe influenced by my dietary requirements and the tartes of where I come from, so recipe for a fish pie/tarte:

fish pie mix, or a fish mixture of your choice

Prawns

peas

chard, chopped (stems and leaves separated)

oat cream

1 puff pastry

nigella and sesame seeds

In a pot, poach the fish in the oat cream over a gentle heat. In the meantime, in a pan, fry up the chard stems with a little olive oil. When the stems have softened, add the leaves and the peas and cook for approx. five minutes. In the meantime, preheat the oven to 180C (fan). Add the prawns, cook for another 3 minutes or so. Reduce the heat and pour in the poached fish and oat cream into the pan, mixing everything well with a wooden spoon. Add salt and pepper to taste. In an oven dish, layer the pie filling, then cover with the puff pastry. Tuck the edges well, prick the pastry with a fork, and spread some nigella and sesame seeds on top. Bake in the oven for approx. 20 minutes or until golden.

‘We tend to think of landscapes as affecting us most strongly when we are in them or on them, when they offer us the primary sensations of touch and sight. But there are also the landscapes we bear with us in absentia, those places that live on in memory long after they have withdrawn in actuality, and such places — retreated to most often when we are most remote from them — are among the most important landscapes we possess.’

— The Old Ways: A Journey on Foot by Robert Macfarlane

VI.

It’s Sunday morning and L. is driving us back inland. Waves flatten and the water desalts until we reach Loch Fyne, where there are a dozen people flying kites. There is a dog so tall it could be a pony, I spy white hair and the wobbly legs of young children, smiles and focused stares, while colourful fabrics dot the overcast sky; I see people navigating their ends of the world.

Margaux

PS. If you enjoy this newsletter, feel free to forward it to a friend, or two. Merci!

further reading:

The Divine Comedy by Dante; The Old Ways by Robert Macfarlane; The Living Mountain by Nan Shepherd; Walden by Henry David Thoreau;

An easy recommendation by name parallel, but: The End of the F***ing World series to watch.

Thank you for reading. The Onion Papers is a reader-supported publication. If you enjoy my work, you can support what I do by upgrading to a paid subscription. You’ll get access to the full archive and weekly entries. It costs £4 per month, or £40 a year, and you can unsubscribe at any time. No pressure: I’m happy you’re here either way.

*If you’d like a subscription, but now isn’t a good time, drop me a line and I’ll comp one for you. I only need your email address; no questions asked.

#17: Madeleines

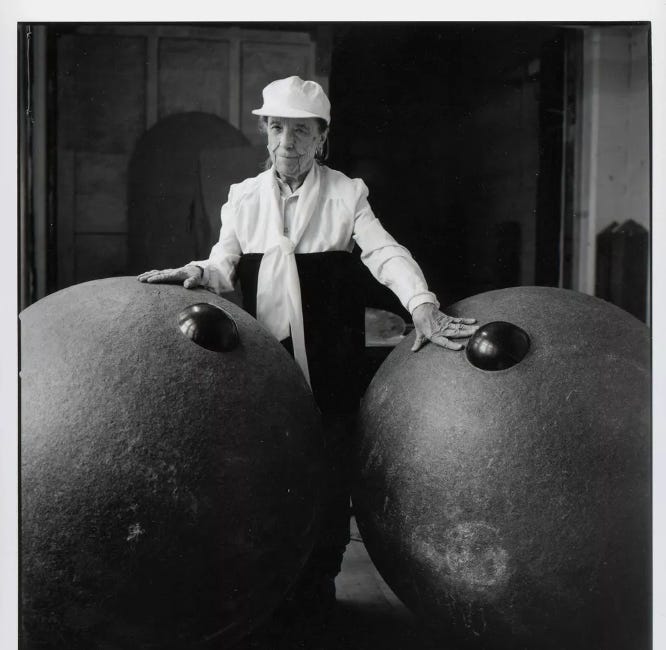

French-born, naturalised American artist Louise Bourgeois said: ‘Expose a contradiction, that is all you need.’ Yesterday was Mother’s Day in the UK and when I think about mothering, I’m likely to use the word contradiction, or contradictory words indeed. The work of Louise Bourgeois, who was best known for her sculptures, (monumental) installations and…