Play Dough: touch as a collective consciousness

Francis Alÿs: Ricochets at the Barbican and a recipe for a beetroot, dill and goat cheese galette

The Barbican Estate is eerily quiet on a Saturday morning. I arrived before 10am, when the light was harsh on the eye; as if the brutalist architecture and the overcast sky had made an alliance in grey, apart from the touches of vegetation that are embedded between balconies and benches. The estate is located above ground level and reserved to pedestrians, cutting off the cacophony from the London traffic abruptly and, behind its walls, ‘No ball games’ signs are displayed on the concrete buildings.

If you aren’t familiar with London, the Barbican was built between 1965 and 1976, on a site that had been bombed during World War II. The estate was designed for City professionals and the flats were let out at commercial rents by the Corporation of London, targeting high-profile politicians, lawyers, bankers and businesspeople. In 2001, The Minister for the Arts, Tessa Blackstone, announced the Barbican complex was to be Grade II listed as an example of concrete brutalist architecture. Today, almost all flats (approx. two thousand) are privately owned, and the Barbican has become a landmark of London’s urban landscape and a show of its long-standing history with wealth disparities.

It is still free to walk through the Barbican Estate.

I visited it often when I was living in London. From the cinema to the art gallery, the plants conservatory and the picnic tables near the pond, on which I liked to study as I went to university in the area. I was researching the depiction of gender stereotypes in children’s books then, specifically the figure of the single parent, conducting field work with pupils in both France and the UK. There are plenty of schools in the neighbourhood, with a wide-ranging cultural, religious and economical diversity. Still, wandering through the Barbican Centre is like swimming underwater – walking up the concrete, high walls and plunging into the white noise of the preserved estate, cut from the reality outside.

Last week, I was in London for a fellowship with the Franco-British council. We ended three days of seminars at the Barbican Centre, where we were welcomed by curator Florence Ostende. ‘It’s as loud as a playground inside’, Ostende explained when she asked us to step outside the gallery, guiding us towards the terrace at the back, so she could introduce Francis Alÿs’s work.

Francis Alÿs: Ricochets is a multi-screen installation and the result of the two decades Alÿs spent travelling over fifteen countries around the world, where he filmed children’s games. From children playing musical chairs in Mexico City, to a group of pupils racing snails in a Belgium schoolyard, or children playing leapfrog in Iraq, the show is deeply immersive as all films are staged in conversation with one another.

Stepping inside the gallery waves through the body as a sensual overload. Laughter, shouting, skimming rocks and jumping feet noises escape from each one of the screens, bouncing back against one another – here, there children have reclaimed the ground. I walked and I smiled at the girl who knocked her knee against her friend’s forehead as she jumped over her back. I froze as I watched three boys playing roles as checkpoint officers, guns in hands and looking proud, at the entrance of a village in Ukraine – and I was moved to silence when I found one of the boys again, on another screen, imitating the sound of the alarm sirens, this time with frightened eyes and staring at us through Alÿs’s camera. Alÿs’s filming style is discreet and respectful – the lens of his camera doesn’t intrude or interfere with the children’s games as they interact with the world around them. He – Alÿs, the artist, the adult – fades away and all we are left with is the ingenuity of play. Regardless of the game being staged, of the landscape – a warzone, droughts and floods, a parking or a fenced and modern playground – the focus is on the connections being forged between children and their surroundings, thus how they negotiate their co-existence as a collective through the creation and duplication of microcosms.

On the second floor of the gallery, there is an iconographic history of children’s games, dating back to the Middle Ages and spanning continents. Whether you’ve played ‘leapfrog’ or jumped above sheep, hares, dogs or deer in your mother tongue, it is likely that you’ve shared common games with the children of another country. And while I’d recommend seeing the show anywhere in the world, there was something about it being staged at the Barbican that made me think harder. I couldn’t unsee the dichotomy between the ‘outside’ and the ‘inside’ divisions of the world. It became apparent, once again, that to reach safety in western, individualistic and liberal communities has become affiliated with sheltering – between high walls, behind a locked door, within a group of likeminded people.

to a world where unborn babies and human lives are slaughtered on camera,

while we scroll through meals and holidays;

to this woodless world,

i ask: who is safe?

— journal entry from 2024

If children aren’t allowed to play inside the Barbican, anyone who can afford a museum ticket can watch children from around the world play on the screens displayed inside the Barbican Centre. The one sentence encapsulates more than one of the nonsensical inequalities and absurdities of socio-economic organisations – and more than I can articulate well in the one newsletter – so, today, I’m interested to look at how touch can help us reconnect with others and the lands around us in an era of mass communication and of disparities.

More than interacting together, the children of Ricochets were skimming rocks in Tangier, stepping on cracks through Hong Kong to wrest a busy public space, or chalking the streets of London. They were establishing connections. They were playing Haram Football on the East Bank of Mosul, which is a re-enacting game of football without a ball, until they’d be interrupted by a burst of gunfire. They were re-establishing lost connections too. And they continue to adapt as the exhibition shows an evolution in the games that are played. In 2021, Alÿs filmed children playing Contagio in Mexico City, which is a post-Covid version of tag, where instead of the touched person being ‘frozen’, they are contaminated by a virus and become viral transmitters. The players wear colourful face masks, apart from the transmitter who is distinguished by a red mask – ‘Contagio!’ they shout as they touch someone, and the victim echoes ‘Contagiado!’, infected, as they put on the red mask. The last one standing says: ‘Survivor!’

Touch helps us to assess our emotions indeed. Neuroscience has linked touch and pain: sensations begin as signals, which are generated by touch receptors in our skin and travel along sensory nerves that connect neurons in the spinal cord, before they relay information to the rest of the brain. Think of a fever that turns the skin into porcelain: touch rationalises what we think first-hand and is part of our thinking process. ‘Do not touch’ signs hung on the walls of museums; I remember the spicy paste my mother would spread on my thumb, so I would stop suckling it, my teeth already misaligned. Touch helps us to understand our environment as much as it sets boundaries about where the land of our personal remit – the body – begins and ends.

If you’ve been cooking and thinking with me at The Onion Papers before, you’ll be familiar with how much I use dough kneading as a vector between what is physical and intellectual in my creative practice. It is also relatively new. The first dough I worked was during the first official lockdown in England, in March 2020, when we made gnocchi with my flatmates. I vaguely remember a disastrous brioche-pastry for a strawberry tart around that time too, but the point is that I began kneading dough when social distancing was enforced on us. That is, when we were touch starved, I returned to my old tubes of colourful Play-doh, except that I also traded them for an edible, doughy mixture.

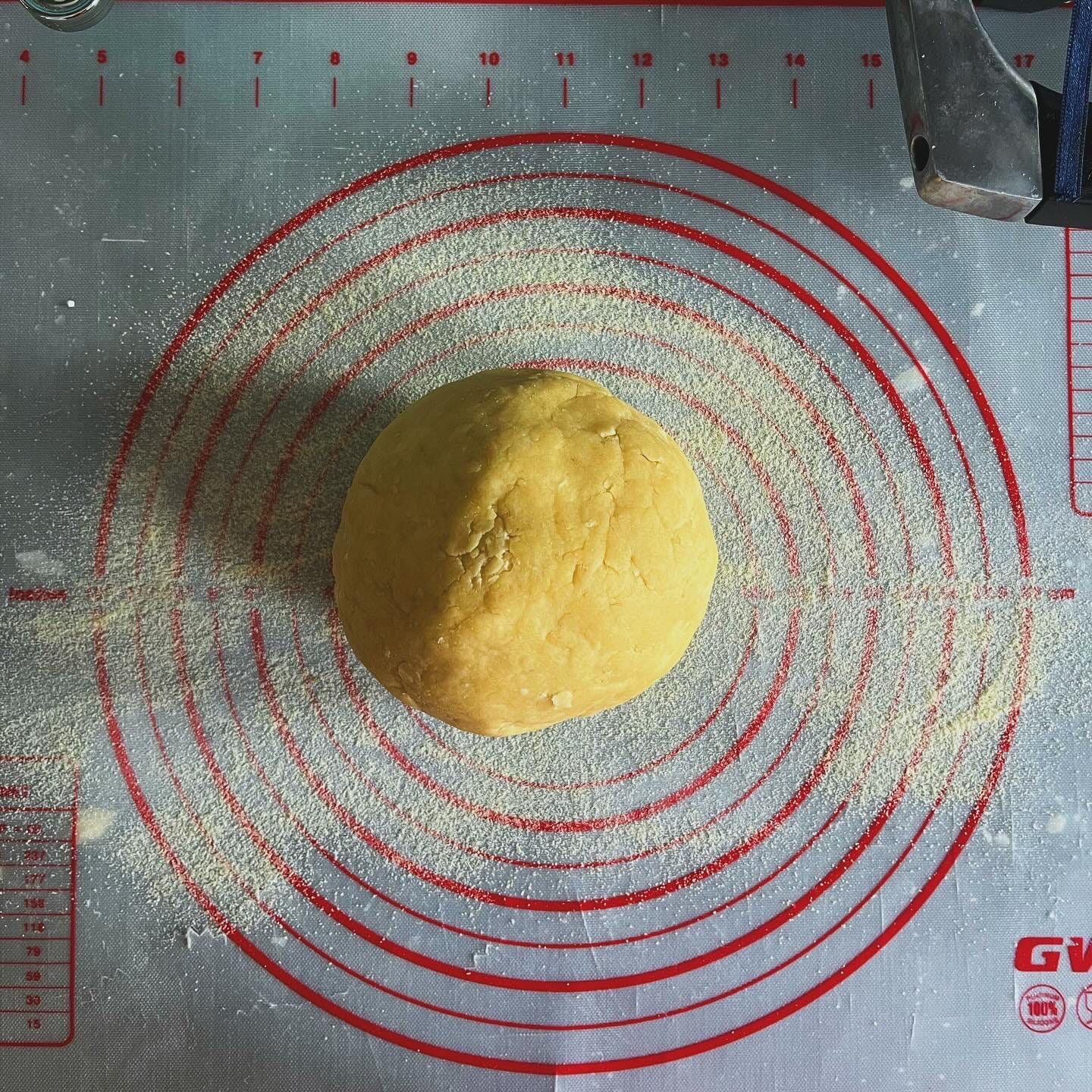

In a large bowl, mix 200g of butter, 50g of semolina, 350g of white flour and a gulp of cold water with your hands. Add a pinch of salt and keep working the mixture until a dough forms. Make a ball.

Artist Barbara Hepworth said about the sculptor that they ‘must search with passionate intensity for the underlying principle of the organisation of mass and tension – the meaning of gesture and the structure of rhythm.’ So do the dough kneaders.

Cover the dough with a kitchen towel and leave it to rest on the kitchen counter for approx. 30 minutes. If the weather is warm, you might consider putting the dough away in the fridge.

Doughs and skins have similar complexions. It isn’t rare to read adjectives such as homogeneous in both recipe books and advertisements for beauty products, setting the societal standards for either a good dough or a beautiful skin. Both hold chemical properties that make them part of a whole – a skin nature or a kind of dough – and specific factors that make each dough and skin unique. I could give you a piece of my sourdough starter, along with a note detailing my bread routine, and you would go home and set to bake a loaf of bread, and yours would taste different from mine. We could put a group of children in the same room, give them clay, and they would mould different figures and find a way to make them play together – to be individual within a group.

It is a coping mechanism to think that what doesn’t look familiar is either irrelevant or unachievable. That it can’t touch us, either physically or emotionally, yet walking amongst children playing, on their own or with a group, echoing one another in their search to carve a space for themselves in this world, it became obvious that anything we think and do, either escaping or confronting, is adding towards our collective subconscious. Or, in Hepworth’s words, ‘the underlying principle of the organisation of mass and tension’.

On a working surface, with the help of a rolling pin, roll out the dough into a galette pastry. Sprinkle some semolina on a baking tray and line the pastry over it.

There is one, single door to enter and to exit the gallery at the Barbican Centre. Next to it, a painting of eyes is displayed, which is presented as a prelude to Alÿs’s Children’s Games film installation. The eyes form a tapestry of coloured irises painted in shades of brown, blue and green, with a golden background that works as a mirror-like surface and reflects the viewer amongst the eyes.

I read in the exhibition’s leaflet that the work is inspired by a 2016 photograph of Yazidi children, taken by the artist in a Sharya refugee camp in Iraq, in which children’s eyes face the camera straight-on to return the watcher’s gaze. Alÿs spent time in Iraq with Kurdish Peshmerga forces near Mosul and, as the Islamic State advanced, local population had to leave their homes and to flee to the refugee camps near the frontline. In a 2016 diary entry, Alÿs wrote: ‘How can one make sense of terror to a child? How can one integrate the un-acceptable? Can a human tragedy be testified by the way of a fictional work?’

More than a prelude to the exhibition, the children’s eyes have become an interlude, hovering over my shoulders ever since I walked out of the Barbican Centre. There is someone looking, always, and however much we want to say that we didn’t know, our history doesn’t end where our knowledge stops. And, in the face of this wild world, I’m privileged enough to call the home kitchen my safe space, where I can break down topics that worry me and scale ideas into concepts that are palpable.

Recipe for a galette with beetroot, dill and feta:

1 pastry dough (as prepared above)

2 eggs

1 generous handful of dill, roughly chopped

150g of feta cheese, cubed

400g cooked beetroot, sliced

1 tbsp nigella seeds

Salt and pepper

Preheat the oven to 180C. In a bowl, beat the eggs. Add the dill (preserved some for the topping), 100g of the cheese, the nigella seeds, salt and pepper. Mix well. Leaving a 2cm edge, spread the mixture over the pastry, then the beetroot slices on top. Roll the edges towards the inside roughly to close the galette. Scatter the remaining dill and feta cheese on top. Bake the galette for approx. 30 minutes, or until golden.

This one always tastes better the next day, cold, sliced and shared.

Margaux

PS. If you enjoy this newsletter, feel free to forward it to a friend, or two.

further reading

Francis Alÿs is a Belgium-born, Mexico-based artist, whose practice ranges from painting and drawing to film and animation. He was trained as an architect and urbanist in Belgium and Italy and became interested in the civic role of the urban environment. He moved to Mexico City in 1986, where he became a visual artist. You can find more about Alÿs’s work at his website.

Ricochets is live at the Barbican Centre until 1st September 2024.

The Children’s Games films are in the public domain and can be watched here.

The Unicef reports that ‘in Gaza, tens of thousands of people have been killed, 70% of whom are women and children. Children have had to leave their homes, often separated from their caregivers.’ If you can, please consider donating to help children in Gaza via the Unicef appeal.

looking ahead

On Monday, I will be sharing some notes about my bread routine for the next edition of the annotated recipes series, or ‘Kneading Club’, which goes out to paid subscribers. If now isn’t a good time to be paying for a subscription but you could use a friend to cook with, drop me a line (margaux@margauxvialleron.com) and I’ll comp one for you. No questions asked.