Woody breakfast table, butter melts on toast; creamy yolk spreads over a slice of malted sourdough; the heel of the baguette, munching and walking home; crunchy, crusty; fluffy as a cushion or crumbly as a nut. Unsalted, seeded; flat, crescent-shaped, round; sesame, white, wholemeal flours. I say ‘bread’ – close your eyes – open, and please describe to me the loaf of your choice and how it tasted.

‘I like reality. It tastes like bread.’ — Jean Anouilh

Breadmaking is one of the most diverse and enduring baking traditions of humankind. It’s contradictory and malleable; there isn’t an essential goodness to how one bakes bread. ‘Bread is the most everyday and familiar of foods, the sturdy staff of life on which hundreds of generations have leaned for sustenance.’ As per Harold McGee’s reference encyclopaedia on food and cooking.

(A disclaimer: this isn’t a research paper about bread or a guide about how to make bread at home as I’m just a bread enthusiast, but I’ll include a list of resources at the end of this newsletter.)

Like most of my peers, I’ve been thinking about what it means to be a writer in a world that breaks apart in more ways than we mean for words to describe them. The images we share when we can’t speak, and the metaphors we run through our heads when we shelter into silence; the banners we paint and the slogans we shout when we run out of time to formulate sentences; the stories that will write themselves later, and that will be rewritten again, over and over again. We write because we live and we read because we write. In that pattern emerges a shared language that connects our solitudes and our fears; the stories we tell to link our experiences.

‘Peace goes into the making of a poem as flour goes into the making of bread.’ — Pablo Neruda

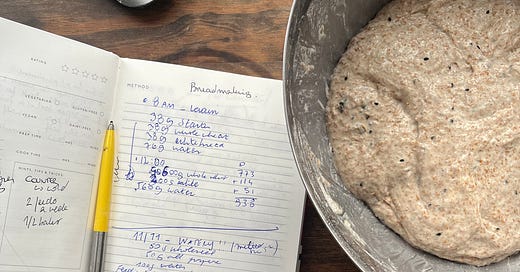

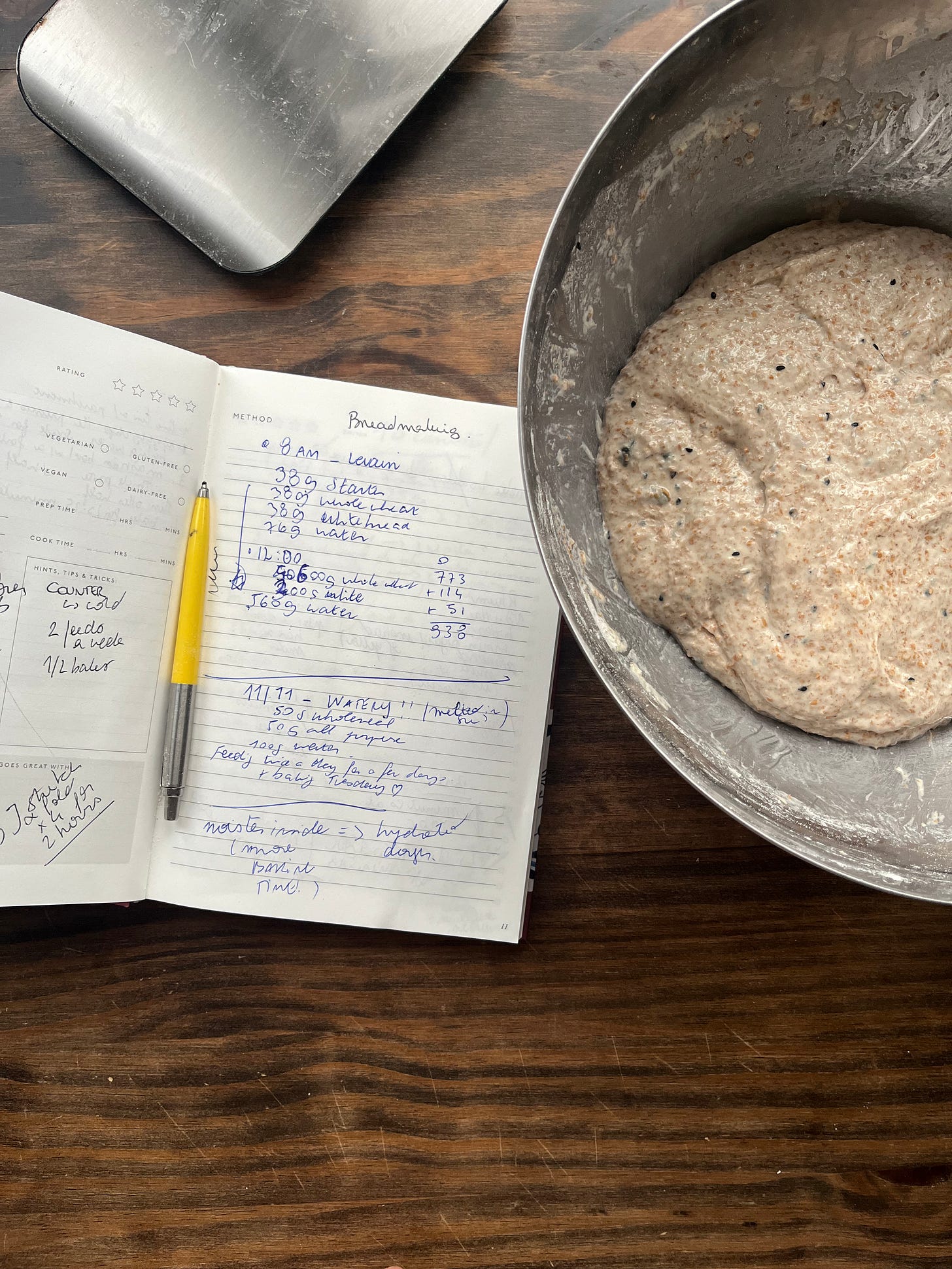

On the last day of October this year, I mixed 100g of wholewheat flour and 125g of lukewarm water in a clean jar. I fed the mixture every day, carefully measuring flour and water, discarding some of it, then I fed it twice a day, until it grew and fell back predictably – into a wholemeal sourdough starter. For the first time in almost a year, a sourdough starter bubbles on my kitchen counter. This small beast that feasts on flour and water is exigent and tolerant. I keep mine outside and I bake once or twice a week: there isn’t any heating in my Glaswegian kitchen, so the environment is chilly enough. Each starter has its individuality and there is no formula: you must get to know yours for it to nurse a good loaf of bread.

As I re-learn to care for a starter and to bake bread again, I'm interested in investigating how breadmaking and empathy interplay in the kitchen. Whether you knead or buy the bread you eat, whether you’ve a sourdough starter at home, make levain, soda or flat breads.

Try to make bread a quick fix and the loaf will taste of yeast instead of wheat. I often feel daunted at the idea of making bread. The recipe length, stretching overnight, the chemistry and monitored temperatures add up as too many parameters that could go wrong. Until I get going – physically making bread – and break down each step into sizeable tasks, so it feels feasible again. Exciting and energising, like the youthful joy of learning something new first-hand, slowly teaching myself and learning from other bakers.

Breadmaking is a wise teacher.

As I bake more often, I have let go of the appearance factor. I’ll always smile at the sight of a golden loaf, but when I’m making my own bread, I rely on odour and touch the most. Honeylike when I work with rye flour, like a meadow on the edge of a summer storm when I knead a wholemeal dough. I’ve come to accept that I can’t trust myself if I’m making a baguette – I’ll smell butter, however plain the flour may be. The dough will strengthen with stretch and fold, but there isn’t a set count; you must feel it becoming robust, raising your awareness of the dough’s behaviour to make it rise.

Breadmaking will call upon your senses and you must awake to them.

Fermentation needs time to generate organic acids and alcohols. I’ll start making bread the day before baking, from preparing a levain with a piece of my sourdough starter, all the way to bulk fermentation and an overnight proof. The full process will require approx. nine steps, with short or longer breaks between each one of them. In “Bread Baking Without Agony”, Laurie Colwin quotes Elizabeth David, who wrote in English Bread and Yeast Cookery: ‘It’s really a question of arranging matters so that the dough suits your time table rather than the other way around.’ I loved this sentence when I read Home Cooking a few years ago, feeling liberated by the idea of bread as self-care; my self craving to be released from the commitment. When I read it again between two kneads last week, it made me pause; I remember my bread from a few years ago as bland. A good bread can’t suit the baker solely – bread is tuned to the emotions more than the clock, turned toward the communal.

(I’ve nothing against Laurie Colwin and Elizabeth David!)

Sustainability matters to the bread maker too. Stale bread will perk a soup like this zuppa di farro e pane from last year.

I’ll never forget how my mother groaned at the price of the baguette after we switched currency, from the franc to the euro. ‘But 1 franc isn’t worth as much as 1 euro,’ she used to say as she placed one baguette instead of two inside our trolley at the supermarket. The price of the baguette has been used as a reference point to measure how expensive general goods are for years.

At a time of climate emergency, the cultivation of wheat and grains has become an urgent topic. Changes in weather patterns will affect our respective breads, regardless of our privileges and ability to look away; the only difference will be when.

Breadmaking unites and must be reassessed with its time.

This is my experience though, and there can’t be one way of making bread. A bread’s beauty isn’t about the density of the crumbs or the thickness of the crust, but the agencies that go into making and eating the bread. The thing is, I could be following my usual recipe or listen to an expert’s advice, I could be doing everything so right, and my bread wouldn’t rise. Preconceptions don’t bake well.

The word ‘dough’, I read in McGee’s encyclopaedia, comes from an Indo-European root that meant ‘to form, to build’, and that also gave us the words ‘figure’, ‘fiction’ and ‘paradise’ (a walled garden). McGee goes on to explain that this ‘derivation’ suggests the importance of ‘dough malleability, its clay-like capacity to be shaped by the human hand.’

So I raise a humble dough. I make bread to learn and relearn with each new loaf; kneading a dough at my kitchen counter to widen the lens through which I experience and see the world around me – watching, smelling, tasting, and asking why I see and smell and taste this way. This is a learning curve, and the learning deepens with reading about the traditions and methods of the bakers who worked before me. I often get it all wrong too; humble, humble dough.

I’m not saying that you’ve to make or to eat bread – that’d be bossy – but I wanted to share some food for thoughts about a tradition I enjoy for its ability to feed and to connect us to one another and to the land. A loaf of bread as yet another reminder that our freedoms are interlinked, baking bread to care and slicing a loaf for community and unity when words feel abstract and unreal.

Just like the books I read, I don’t like bread to go unshared. A non-exhaustive list of things I like to eat on toast, in no particular order:

butter and anchovy paste, dill and white pepper on top;

tinned sardines, mashed into a paste with miso, sesame seeds and soy sauce;

sliced tomatoes, oregano, rock sea salt;

chard (boiled), poached egg;

grated garlic, cavolo nero, mozzarella (recipe);

peanut butter (crunchy).

Knead, a dough rise; raise to rage and love.

Margaux

further readings and resources:

On making bread:

Andrew Janjigian’s ‘breaducational’ substack

is my reference.Breadsong by Kitty Tait and Al Tait is a brilliant cookbook for the baker inside you. Or for the baker-to-be in your life.

Thinking about bread, wheat production and land justice:

I can’t recommend enough listening to

’s Lecker podcast series — The Making of Good Bread — a three-part series in collaboration with Farmerama Radio. From the show notes: ‘It considers standardised grain testing and the possibility of reimagining measurement within the system that surrounds bread production.’ The wheat tasting workshop during the 3rd episode brought me pure joy on a rainy run.Also recommended to me by Lucy, Farmerama Radio’s Cereal series with Katie Revell.

Resources at UK Grain Lab.

Decolonize the Garden on Instagram and

on Substack.Environmental Justice in Palestine toolkit from Intersectional Environmentalist.

Feel free to share more resources in the comment, fellow friends of the pain.

Thank you for reading. If you enjoy the work that I do here and if you can afford it, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription. Recipes and notes on craft are sent on Mondays via TOP Kneading Club; long-form essays are dispatched every other Thursday.

You can read more about my novels here.

So honored, Margaux! ❤️