Drafting in Kitchens

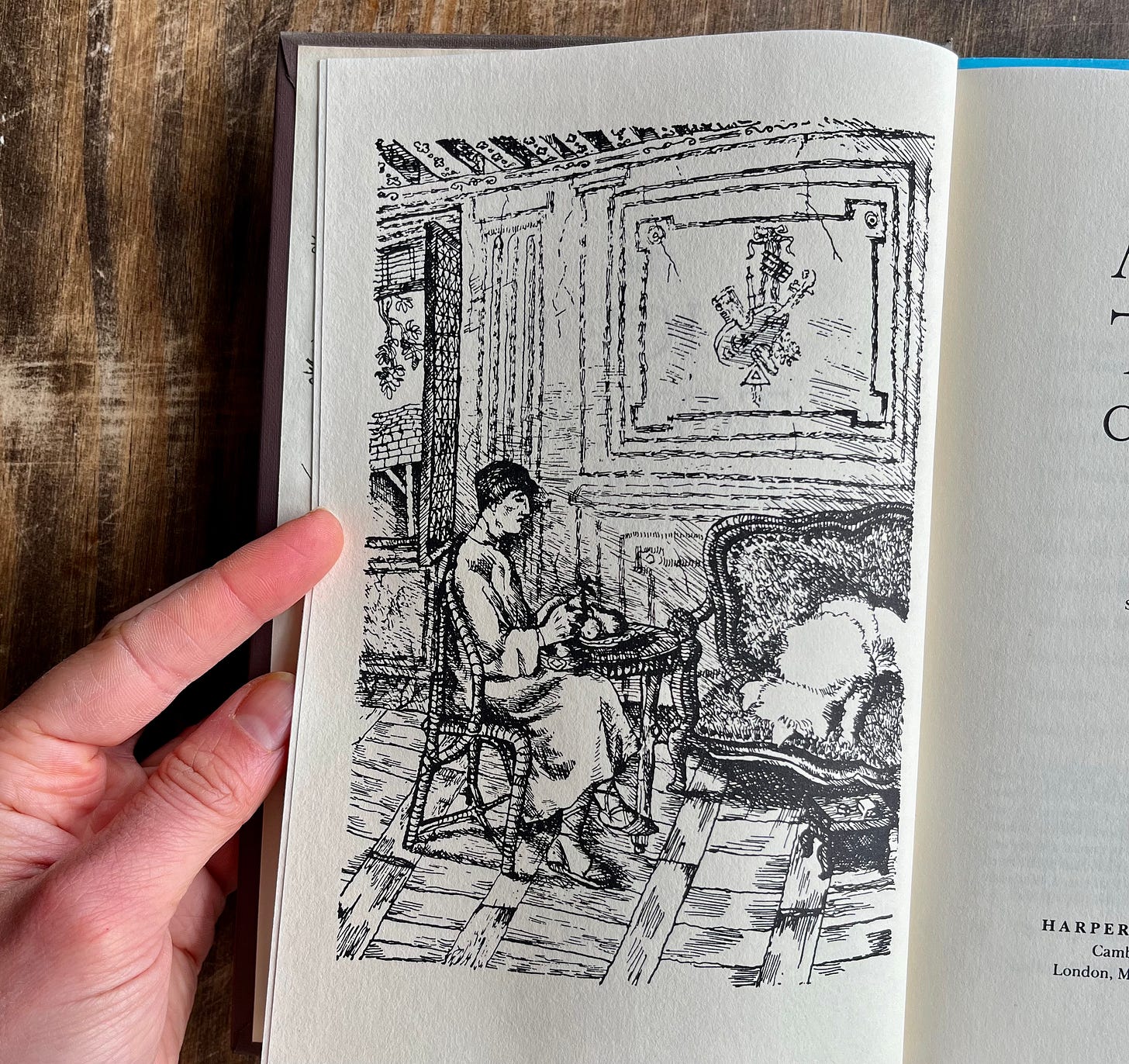

rue de Fleurus with Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas; a friend's recipe for brothy beans

Years after Gertrude Stein’s death, a ‘young publisher from New York’ asked Alice B. Toklas to write a book about her life with Stein. Toklas refused. To the publisher’s disappointment, she explained that, with the publication of The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, Gertrude, who was an American writer and art collector, had done Alice’s autobiography already. Then Toklas suggested, ‘as tentatively as she was able, which was not very,’ that she could write a cookbook instead. And ‘it would, of course, be full of memories.’ To cook is to tell a story.

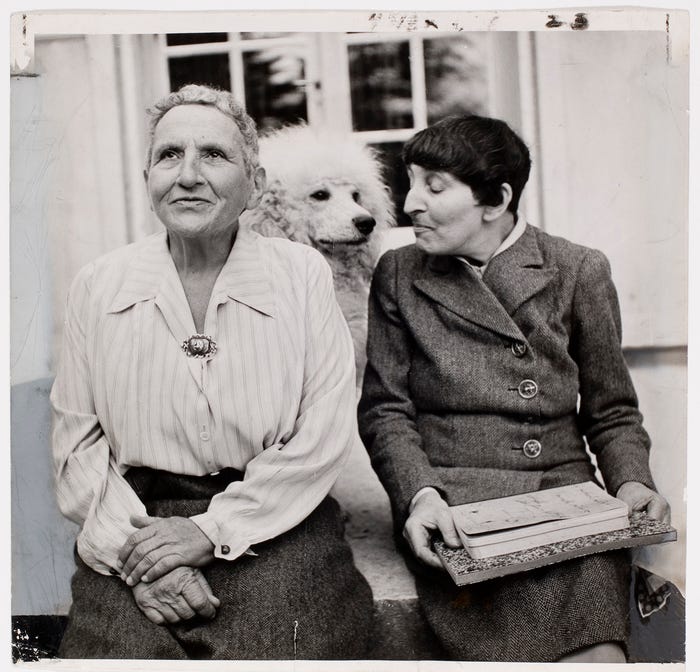

Gertrude Stein was born in Pennsylvania in 1874 but spent her earliest years in Austria and Paris. When the Stein family returned to America, they moved to California. After the death of her parents, at the age of eighteen, Gertrude Stein moved to Baltimore and graduated from the Harvard Annex in 1898. She continued her studies at the Johns Hopkins Medical School – leaving without a degree because she was ‘bored, frankly and openly bored’. From 1903, Gertrude Stein and her brother settled in Paris and began to collect paintings collectively, and she to write. During the years before the First World War, she grew to know an influential group of painters and writers, including Hemingway, Matisse and Picabia, who also became her friends. Alice Babette Toklas, who was born in San Francisco in 1877, joined them in 1907. She then moved into Stein’s apartment rue de Fleurus, in Paris’ 6th arrondissement, and the two women went on to be life-partners. During both wars, Toklas and Stein remained in France and Gertrude continued to write. She died in 1946. By then, she had become one of the century’s most publicised but least read authors, and she had influenced three generations of writers. Toklas died in 1967; the two women rest at the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris’ 20th arrondissement.

A few years ago, I hit a wall with my health. I felt lonely and useless in the kitchen as the effort to cook for one drained my appetite, until I started reading The Alice B. Toklas’ Cook Book (1954) in parallel with Stein’s Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (1933). There, while I was physically unmoving, a new world opened before me. The two books burst with the recognisable names of intellectual figures, and unknown names I’ve become fond of along the years, like Aunt Pauline. Toklas’ cookbook interlinks recipes with short but generous accounts about the social bubble that rounds a meal, in that they are careful and honestly rooted in the domestic life of the Stein-Toklas pair. They are, in a certain manner, genuinely biassed, while Stein’s Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas is a playful show through which the reader’s eye is subjected to the voyeur’s passions. On a few occasions, the same event is repeated in the two books, which I assume to be subconscious (perhaps wrongfully, and Alice was having her revenge for that autobiography of hers!), and disparities appear like needles through details, slowly picking holes in the couple’s appearances. Or, to stay grounded like a cook set forth to prepare a dish, new-born subtleties expose their intimacy; a shared life – a mirror of Stein looking at Gertrude through Alice and of Toklas looking at Alice and Stein and friends through her cooking, which is obviously influenced by Gertrude Stein’s taste and their friends’ dietary requirements. Without a fuss, Alice B. Toklas comes across as a good host. The painter Pablo Picasso, for example, visited the Stein-Toklas household often:

‘She is passionately addicted to what the French call métier and she contends that one can only have one métier as one can only have one language.’

— The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas by Gertrude Stein

Stein goes on to detail that Stein’s advice and criticism had become invaluable to her friends along the years. When Pablo Picasso came to visit, specifically, and Stein commented on the illustrations he had shown her, they would entertain each other with long conversations.

And Toklas writes:

‘They sit in two little low chairs up in her apartment studio, knee to knee and Picasso says, expliquez moi cela. And they explain to each other. They talk about everything, about pictures, about dogs, about death, about unhappiness. Because Pablo is a Spaniard and life is tragic and bitter and unhappy. Gertrude Stein often comes down to me and says, Pablo has been persuading me that I am as unhappy as he is. He insists that I am and with as much cause. But are you, I ask. Well I don’t think I look it, do I, and she laughs.’

— The Alice B. Toklas Cook Book by Alice B. Toklas

In her cookbook, written years after Stein’s death, Alice B. Toklas brings context to Picasso’s visits to the apartment rue de Fleurus. Toklas writes in the first person, in her name, whereas Stein had distanced the author via the third person. When Stein had conceptualised a life, drafting a manuscript based on the interpretation(s) of a past scenario, Toklas adds layers as events unfold. Toklas tells us:

‘One day when Picasso was to lunch with us I decorated a fish in a way that I thought would amuse him. I close a fine striped bass and cooked it according to a theory of my grandmother who had no experience in cooking and who rarely saw her kitchen but who had endless theories about cooking as well as about many other things. She commended that a fish having lived its life in water, once caught, should have no further contact with the element in which it had been born and raised. She recommended that it be roasted or poached in wine or cream or butter.’

Alice B. Toklas moves on from one anecdote to the other swiftly, gifting the reader with a recipe for a court-bouillon in this case. She slows down to specify how she served the fish – because she was ‘proud of her chef d’oeuvre’, and Picasso ‘exclaimed at its beauty.’ Then Toklas wraps up the story with an insight only the reality of life as it happens in a flash, as the narrator (miss-)remembers, rather than the intellectualisation of an event, can indulge. We learn that Picasso was on a strict diet, an information which Toklas weaves in with reasoning for her cooking for Picasso; how she amended recipes and favoured certain ingredients, even during the World War and the Occupation of France. If Stein had described Picasso’s diet as thoroughly in her ‘autobiography of Alice B. Toklas’, it’s likely the critique would have pointed out her digressive nature.

If I care about Picasso’s diet it isn’t (solely) because I’m being nosy, but because the information contextualises the painter’s conversations with Stein. Not the topics they discussed as such – (I don’t need to know what the philosopher snacks before I engage with their ideas, rest reassured.) – but that they had that relationship. They didn’t just sit in Stein’s studio, they shared a table and meals in between as well, and regularly enough for Toklas to adapt her cooking to Picasso’s dietary requirements at a time of food rationing and war. They deeply influenced each other. That is, more than with ideas, but with what nourished them primarily and secondly, physically and intellectually.

I’ve never cooked from The Alice B. Toklas Cook Book, but I have gulped its pages like a novel. I’ve forwarded a photo of the recipe for a ‘tender tart’ to friends like I’d send back a heart without any words on days when talking doesn’t fit. I hold it close like a companion.

To share a table with someone is an intimate experience. There isn’t anywhere to hide around the table – olfactory whims, muscle movements from the chewing of the food, the texture of a certain ingredient inside the mouth, the facial reaction of tasting something unexpected. Anyone who asks a person about what they ate growing up, if they do so with attention, is asking about the socio-economic and political climate, as well as the landscape, in which the person became who they are today. Talking about food is being seen – reading is looking to be seen – writing is showing.

‘It was fried but so light’; ‘It wasn’t even that sweet’ I often hear people add swiftly after they tell me about a snack they loved recently. I’m not that self-indulgent!, hear hear; I didn’t think you were indulging. But the quoted sentences are two shows of how expectations influence our taste – the taste we actually taste and respond to, chemically, neurologically, affectively, and the taste we want to be experiencing. I also wish I could say that I read X and understood it and loved it. I didn’t. It left me cold. To dip the slice of an apple in my coffee warms my heart though. It’s a tough act to be, or to feel like we’re at least, the first one to fall in love, and to be caught for it.

This is why drafting in kitchens matters to me, metaphorically at least. As much as the cook should query the origins of the ingredients they use, as an author, I believe that the one responsibility of the writer is to stay truthful to their language. ‘Her métier is writing and her language is English,’ wrote Gertrude Stein. It took me years to build that confidence but, today, I’d rephrase and say: ‘Her métier is writing and her language is Margaux’. In the same manner as there is only the one dish we could ever eat at that person’s home, there are the books only that writer could have written, the hug only that friend could have given. To draft in kitchens is to infuse either the cooking or the writing with a person’s identity in all its contradictions, glories, disappointments and dullness – not the idea of what a life should be, but how a life was lived.

Back to The Alice B. Toklas Cook Book, in the chapter ‘Dishes for Artists’, we learn that before coming to Paris, Alice B. Toklas wasn’t interested in doing any cooking. When Toklas moved in with Stein rue de Fleurus, Stein insisted they’d have ‘American food for Sunday-evening supper.’ The servants would be out of the kitchen on that day (and Stein ‘had had enough of French and Italian cooking’), so Toklas would have the kitchen for herself. This is when, she explains in the book, that she started to cook the simple dishes she had eaten before in California – fricasseed chicken, corn bread, apple and lemon pie. Then came Thanksgiving and the long-ingrained traditions such a celebration would re-enact, forasmuch Stein ‘was not being able to decide whether she preferred mushrooms, chestnuts or oysters in the dressing.’ So Toklas included all three ingredients in her version of the turkey. ‘The experiment was successful,’ Alice B. Toklas writes before she adds: ‘and frequently repeated; it gradually entered into my repertoire, which expanded as I grew experimental and adventurous.’

When I speak with other writers, we often seem to be refrained by the same enthusiasm for the craft. We spend more time talking about what we’ll be writing, or researching topics around what we’d like to write, than to write. I also often talk about what I’d like to cook for dinner, before I scrap that and make the same dish on repeat. To break that pattern is what Toklas calls ‘experimental and adventurous’ – or to find a balance between being respectful in knowing where we have come from in terms of influence and where we are heading as an individual who bears moods and terrors of their own. When I come to yours for dinner, I want to taste your cooking, and when I talk to you, I want to hear your version of the story about yourself. I don’t want you to try to be authentic with me, I simply want you to be with me now, so I will glimpse at you then. You may respond that I’m exigent, but that’s how I can truthfully say that I would like to eat your food.

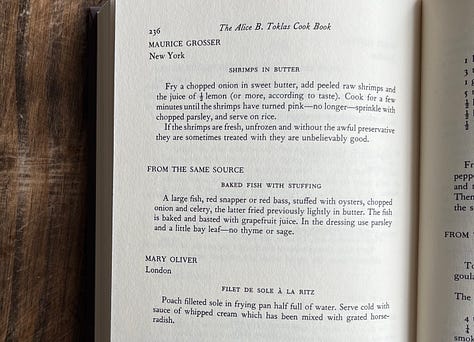

Towards the end of The Alice B. Toklas’ Cook Book, there is a chapter called ‘Recipes from Friends’. It’s a simple list of recipes, each preceded by the name and location of the friend who passed it onto the household. This contextless list is the chapter that moves me the most – like a will, or a raw archive that somehow encapsulates the entanglements of life as a shared experiment, the names who live long with us and the names who have left us, the names whom we have failed and the ones we remember always.

Margaux Vialleron

Glasgow

Brothy butter and broad beans, topped with grilled asparagus

In a large casserole, gently fry 1 tsp of aniseed, 2 tsps of basil seeds, the zest of one lemon and one sliced leek with some olive oil. Add the harder bit from the asparagus stems, swirl in for a minute or two, and grate one garlic clove. Open a can of butter beans, set the beans aside and pour the preserving water inside the casserole. Bring to the boil (you may top the water if you prefer it on the brothier side). Add one vegetable stock and make sure it dissolves. Add the fresh or frozen broad beans and lower the heat to a gentle simmer. In the meantime, grill the asparagus tips using your preferred method, either in a pan or in the oven. When they’re about to be ready, maybe three minutes or so before, add the butter beans to the casserole with the juice of half a lemon. Simmer, add the grilled asparagus and mix well. It’s ready as soon as the consistency appeals to you. A squeeze of lemon juice and a grind of white pepper on top is recommended.

This one is for Alice and Gertrude. And Picasso, and friends. And me and you,

Margaux

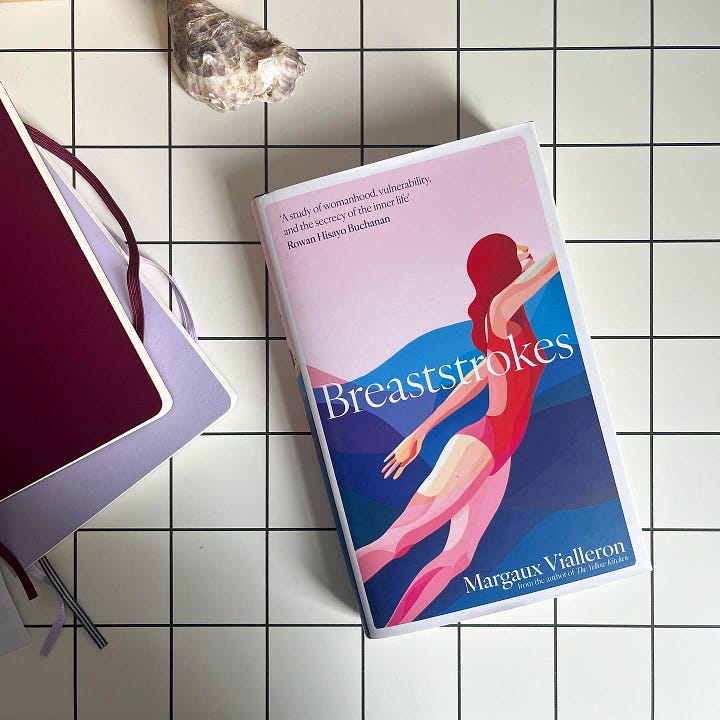

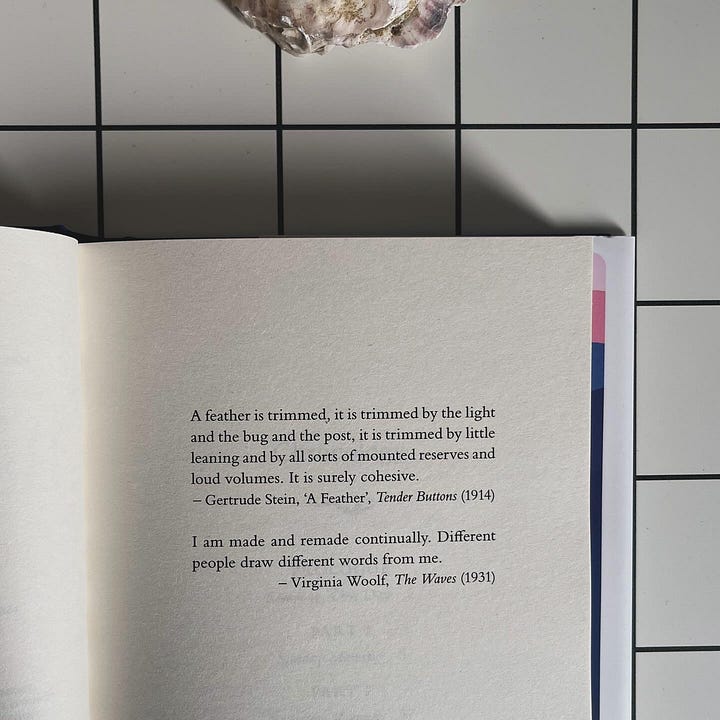

PS. today, Thursday 2nd May, marks one week to the publication of my second novel, Breaststrokes. If you enjoy this newsletter, I hope you’ll consider buying a copy at your favourite bookshop; it means the world to me, so thank you.

further reading:

The extracts in the first paragraph of this newsletter were taken from the introduction to the 1986 US edition of The Alice B. Toklas Cook Book, which includes a foreword by M.F.K. Fisher.

On my bookshelf: Tender Buttons by Gertrude Stein; Picasso by Gertrude Stein; The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas by Gertrude Stein; The Gastronomical Me by M.F.K. Fisher

On Mondays, for paid subscribers, I write a series of annotated recipes – a writer who cooks’ notebook – and last week was for a love letter to April and three pesto variations. I often write about artists and authors and their kitchens, like Marguerite Duras and Louise Bourgeois. You can join us by upgrading your subscription to a paid one, or drop me a line if now isn’t the right time and I’ll comp one for you (no questions asked).

Reading your recipe for the brothy beans reminded me of my mother. She would always use the conserving liquid in canned veggies in her recipes calling it "Gemüse Wasser" aka vegetable water. To her--a child of World War II -- it was a valuable commodity. Growing up, I always thought it tasted gross. 🤣 I usually cook my beans in beer or chicken broth or both. But I want to thank you for poking me with a Mama reminder. She died last August at 94 years. I will make your recipe today --but will use chicken broth & beer 🤣. I never got over the canning taste of the Gemüse Wasser. On second thought...to be adventurous...I could use a white wine maybe? 🤔