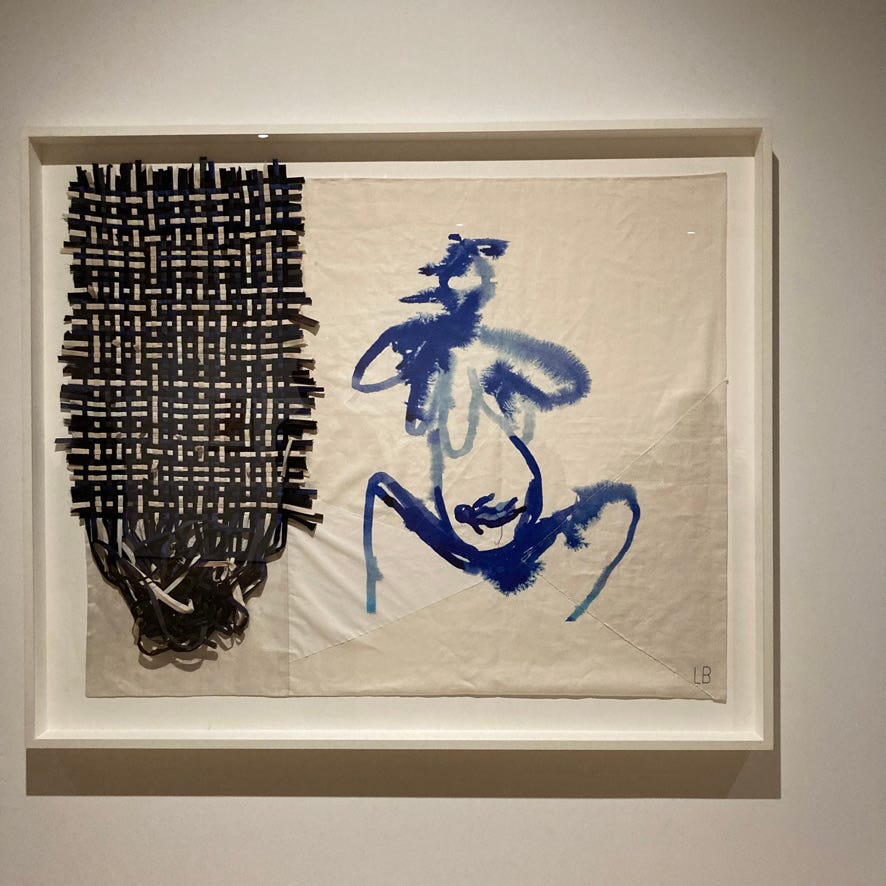

French-born, naturalised American artist Louise Bourgeois said: ‘Expose a contradiction, that is all you need.’ Yesterday was Mother’s Day in the UK and when I think about mothering, I’m likely to use the word contradiction, or contradictory words indeed. The work of Louise Bourgeois, who was best known for her sculptures, (monumental) installations and paintings also haunts my emotions about ‘Mother’. As a writer, archivist and linguist, I’m indebted to Louise Bourgeois—the artist who mended psychoanalysis with art-making—so this week’s newsletter is for LB (as she signed off).

Louise Bourgeois played with the concepts of memory and psychic. The art she created and exhibited is powered by a bundle of desires – repressed, explosive and satisfied desires all at once. Bourgeois tore the rigid, gendered definitions of family, identity and domesticity apart, intertwining her fears and traumas with art-making. To me, Louise Bourgeois’s work embodies a word that is often used as a weapon against women’s recognition and welfare, and to prevent them from accessing equal opportunities : emotional. I’m grateful to her for showing me this.

Louise Joséphine Bourgeois was born in Paris on 25 December 1911 to Joséphine Valerie Bourgeois and Louis Isadore Bourgeois; she had two siblings. The family owned a gallery on the Boulevard Saint-Germain where they repaired Medieval and Renaissance tapestries. When Louise Bourgeois was 12 years old, she was tasked to help in the tapestry workshop. She became an expert at drawing legs and feet, a skill which will later transpire in her work with both sculptures and fabrics. Bourgeois also studied at the École du Louvre and the Beaux-Arts in Paris, and she travelled to Russia and Scandinavia, where she received further education.

In 1938, Louise Bourgeois moved to New York City with her husband, Robert Goldwater, who taught Art History, and she enrolled at the Art Students League. In 1939, Bourgeois and Goldwater returned to France briefly to adopt Michel; they gave birth to Jean-Louis Thomas the following year, and to their third child, Alain Mathieu Clément, in 1941.

Her first solo show –‘ Paintings by Louise Bourgeois’ – consisted of 12 paintings and was held at the Bertha Schaefer Gallery in New York in 1945. She exhibited alongside Abstract Expressionist artists, including Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, and she met European artists, who were exiled by World War II, such as Le Corbusier and Joan Miró. The same year, Bourgeois was included in the group show ‘The Women’ at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century Gallery in New York. Her first solo show for her sculptures took place at the Peridot Gallery in New York in 1949; she started to work with materials such as plastic and latex in the 1960s. The late 60s were marked by Bourgeois' activism with feminist waves and her creations became more explicitly sexual and sensual, with Femme Couteau (1969-70), for example. She continued to create and to exhibit prolifically through her life – and Louise Bourgeois was the first woman to be given a retrospective at the MoMA in New York in 1982.

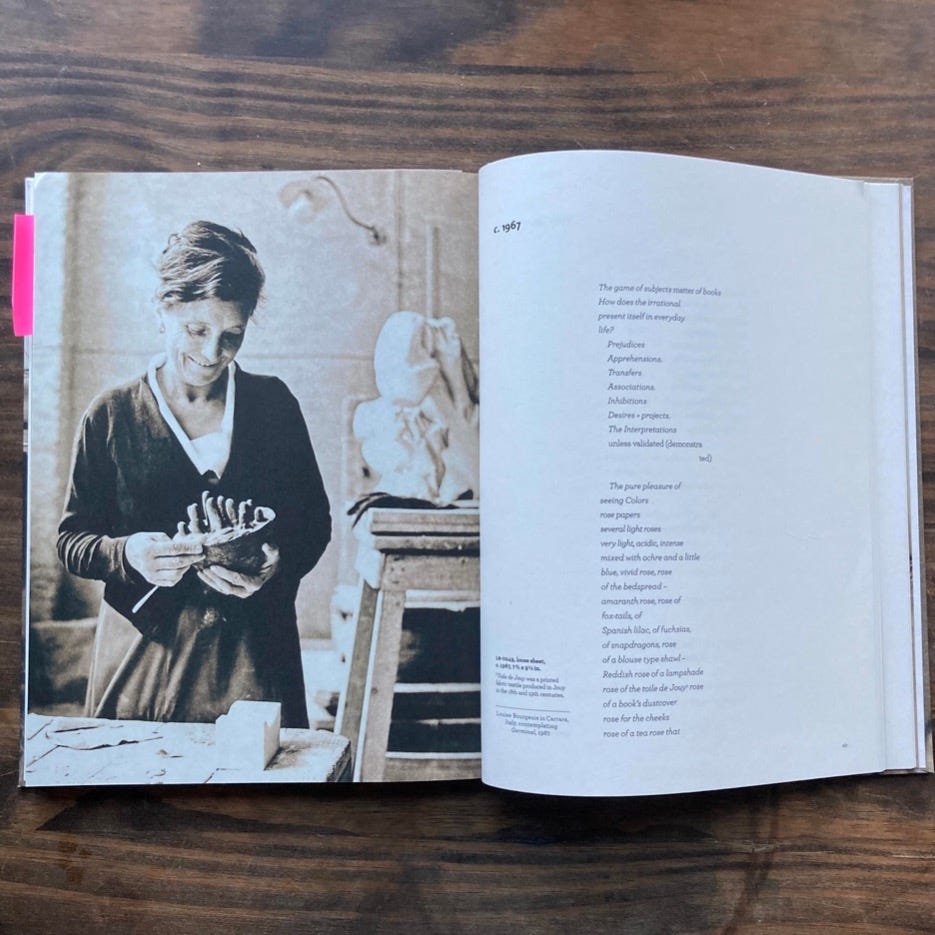

‘Art is a guarantee for sanity’, Bourgeois said. The artist suffered from insomnia and when LB couldn’t sleep, she drew. I’ve written about my struggles with sleep before, and I’ve nurtured a kinship while reading Louise Bourgeois’ diary entries. Bourgeois, I read in Louise Bourgeois: The Return of the Repressed (edited by Philip Larratt-Smith, 2012), ‘was compelled to remember everything in order to hold on to her past, and at the same time wants to forget the past in order to live in the present.’

‘I am hip, jip, jip = depression coming

the orange eggs versus the ergot

relation of appetite to depression.

saucisson at 6 in the morning.

the stealing of the 2 slices of bread.’

— Louise Bourgeois, diary entry dated 7th January 1957

Louise Bourgeois was an intellectual artist who had studied mathematics and geometry before turning to the arts, after the death of her mother in 1932. She was well read and opened an independent bookshop, called Erasmus, in NYC later in life. From her collected diaries, it transpires that she loved dictionaries and preferred poets to prose writers – and she wrote most of her diaries in verses. Bourgeois switched freely between English and French, sometimes making up words at the midpoint between the two languages.

<3

‘For me, l’enfer d’être sans toi, the absence of the other.’

— Louise Bourgeois, undated diary entry

As I mentioned earlier, Louise Bourgeois was fascinated by psychoanalysis. She also underwent personal psychoanalysis, and she read Melanie Klein’s books. She documented her life faithfully, recording and detailing each aspect of the everyday, from her doings to her thoughts and her symptoms. These archives were central to her creative and thinking process. Bourgeois believed that the artist has a privileged access to the unconscious and the skill to render something psychic tangible.

Ever since her father had started a long-term affair with her home-school tutor when she was a child, Bourgeois had a difficult relationship with her parents. ‘She was brought in for me’, she later said. Bourgeois suffered from depression and, at times, agoraphobia. During these episodes, she found shelter in her craft since her work was informed by her life experiences and traumas; she called her method a ‘ritual movement from passive to active’. That is, to create through actions such as cutting, drilling and carving.

‘I value my method

that is all I

can trust

the abdication:

all my production

is an apology, it is

very difficult to realise

to understand this

remark, and it is my

duty to explain myself’— Louise Bourgeois, undated diary entry

When her husband died on 26 March 1973, Louise Bourgeois tore the kitchen inside her Chelsea flat apart. She was done with the domestic but kept making art. Louise Bourgeois transformed what was once a household for the Bourgeois family into a studio of her own. ‘I’m using the house. The house is not using me.’ Bourgeois said about her workspace, where she scribbled phone numbers on walls and pursued the most prolific period of her career.

Louise Bourgeois’ productivity was immense and her art impactful. Some of her most famous artworks include Femme-Maison (1946-7), Forêt (1953), Fillette (1968), The Destruction of the Father (1974), Maman (1999), Spiral Woman (2003). She received Honorary Doctor of Fine Arts degrees from Yale University in 1977 and another one from the Massachusetts College of Art in 1983. She was awarded ‘Officier de L’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres’ by the French Minister of Culture in 1983, and she was elected a Member of the American Academy and the Institute of Arts and Letters in New York (still in 1983). She curated exhibitions internationally and was awarded many prizes for her art, including the first Lifetime Achievement Award from the International Sculpture Centre in Washington (1991). During the year of her death, 2010, the Kukje Gallery in Seoul exhibited the show Louise Bourgeois: Les Fleurs, she had her first exhibition in Athens and had some of her works exhibited in Stockholm and Venice. Bourgeois also finished the installation The Damned, The Possessed, and The Beloved that same year (started in 2007), which she dedicated to the seventeenth century’s witch hunt victims.

There isn’t one Mother’s Day I wouldn’t want to spend thinking about the figures Louise Bourgeois knitted and stuffed with fabrics and objects, the lines she sketched and splattered with red paint, the emotions she sewed and casted into sculptures.

I can’t find a rational explanation for this, but I identify Louise Bourgeois with eating vanilla, cloudy madeleines. Recipe for 12 madeleines:

50g brown sugar

150g flour (I use 00 type to keep them airy)

2 tbsps of vanilla extract

1 tsp of rum

8g yeast

50g butter, melted

2 eggs

40 ml almond milk

1 pinch of salt

In a bowl, beat the eggs and the sugar until you’ll have a homogeneous mixture. Add a pinch of salt, the vanilla extract, the rum and half of the milk quantity. Add flour and yeast. Mix well. Add the melted butter and the rest of the milk. Mix and leave the dough to rest for one hour, somewhere warm and covered under a kitchen towel.

Preheat the oven to 200C fan. In the meantime, prepare a madeleines-shaped oven dish with butter. Pour some of the preparation in each one of the madeleine moulds, filling them at approx. 2/3 full. Bake for 15 minutes, or until golden.

‘I’m ready

I have everything the

circumstances ask of me

therefore, I can fall asleep’

— Louise Bourgeois, diary entry c.1965

I’m just back from Campbeltown, so I’ll pair this week’s batch of madeleines with a dram of Kilkerran 12 years old.

Margaux

Thank you for being here. The Onion Papers is a reader-supported publication; feel free to like this post, and to forward it to a friend or two.

further reading:

Two episodes from The Great Women Artists podcast with Katy Hessel: Jo Applin on Louise Bourgeois and Siri Hustvedt on Artemisia Gentileschi, Louise Bourgeois, and more.

A Look Inside Louise Bourgeois’ Home via The New York Times.

Louise Bourgeois: The Return of the Repressed (edited by Philip Larratt-Smith, 2012)

Sheila Heiti’s Motherhood will always be one of my most precious reads.

An extract from The Yellow Kitchen:

Last week week marked two months until the publication of my second novel, Breaststrokes, and I’m an excited/nervous author. I’ll share some news about events soon, and it’d mean the world to me if you would consider pre-ordering a copy. It should be available from your favourite bookshop, otherwise here are some links. Pre-orders really help, so thank you.

Part of the research for this newsletter (about Louise Bourgeois’s life) was conducted and published in a previous newsletter, for the SPK book club, which I co-host with Irene Olivo. The menu was different and I wish I could share it with you, but sadly the server we used at the time, TinyLetter, doesn’t exist anymore. However, I’m using this opportunity to remind you that we always welcome new book club members. You can find more information about our next meeting and read at our website.