cooking with fire: an interlude

eating and travel notes from two Scottish islands; thoughts on purpose; unmeasured recipes

Inside the bothy, there is no electricity supply but a wood burning stove with a kettle on top. Place firelighters inside the stove’s belly, add the kindling, lay a couple of wood logs over it, then light the first flame and pay attention. There wouldn’t be any sparks without your intervention. Keep the door open to allow enough oxygen in, let the fire intensify, then close the valve, fill up the kettle and wait for the water to boil. A drizzle of olive oil inside a fire-proof pot, a sprinkle of leftover salt and paprika from those who had stayed overnight before, pour in a can of tomato sauce. Feed the fire with more logs – sizzle. Add a can of pinto beans and a jar of roasted peppers (each drained), stir. There is no such a thing as simmering or slow cooking with a chirpy fire; cook, settle, the smoke thickens fast and the visibility around you narrows; whenever and wherever you are, always open the window before you start cooking.

‘Get that fire starting as soon as you get there,’ the ferryman had told Ludo and I as he dropped us off on Ulva. ‘It is a long walk,’ he added.

The sky and the sea wore matching colours as waves and clouds curled with the wind. We had taken two ferries to reach that far into the Inner Hebrides and were now walking across it as all cars have been banned on the island, towards Gometra. The light was dimming as the rain poured over the horizon line, trotting towards us, a little menacing but nothing too threatening by Scottish-weather standards; enough to keep our pace up despite the weight of our backpacks. On a cliff, the gale blows with a purpose, tides instead of time, the face and form of rocks for clocks.

Fire rituals, whether they are practical or spiritual, are present in plenty of traditions and cultures. Historians have long debated when humans learnt to ignite flames purposefully rather than to use fire after it had occurred organically from lightning or other natural events. Fire is a source of energy, warmth and light, but it isn’t an element. It is a chemical reaction called combustion which, as earthlings understand it, can only occur on Earth (where oxygen is abundant).

The next day, I woke up before the sun rose and let the dog out, my breath drawing a luminous fog against the lilac of the early hours, waves exhaling into the gorge below my feet. Leopoldo went for a stroll, and I returned to the stove – firelighters, kindling, logs, kettle – and sat in front of it, my blood vessels unlocking the gates inside me, my fingers swelling red from the heat.

In the Bothy’s handbook, I found handwritten entries from previous visitors going as far back as 2015. I read about the island’s landscapes and wildlife through the eyes of others, I who had not been so lucky with otters, and who wouldn’t see the autumn leaves fall and reveal the two local Bens, as well as plenty of advice about what to cook with the stove, such as sorrel from up the valley to give a bland pasta a touch, a pita bread recipe, tips on how to wrap potatoes in foil, skin on. Each author spoke about heartfelt plenitudes but nobody mentioned the purpose of their visits. Underneath each one of the dated entries, words drifted, from one point to the next sentence, punctuation as markings for a past human presence, open sentences, nothing definitive. My reading was fragmented too, curious but mindful of one’s intimacy and how my intrusion would reflect on my respective right to privacy, the fire frizzling and grounding me. A fire can double in size in sixty seconds.

The definition for purpose, as I found it in the dictionary just now, is as follows: why you do something or why something exists.

Oh, I have felt cold and impatient, hungry and thirsty as we played cards or interpreted the fading painting above the fireplace with L., until I surrendered and the same wait eased me, purposeless, guided by my ears instead of my expectations. Hearing tunes in with details. And, as the stove began panting, before steam came through the kettle’s pouring spout, a chain of actions and reactions had kicked in. I may have been alone, but my doings aren’t unique.

‘Eternal fire, That inward burns, shows them with ruddy flame Illum'd’, Dante wrote in the Canto 8 of The Divine Comedy as the souls of those in Hell are illuminated.

In a cup, pour one spoonful of instant coffee and stir in some boiled water. In a bowl, beat some eggs and season with salt and pepper; set aside. Lay some foil over the stove and place halved English muffins on top so the crust will crisp. In the meantime, in a fire-proof pot, warm up some olive oil, stir in the beaten eggs and, as they cook, keep pushing the egg mixture from the tip to the core of the pot, gently scrambling them. If you are after fluff without dairy, this is an affair of patient resilience. Serve (bonus: crisscross some anchovies on top).

‘There must be something in books,’ Ray Bradbury wrote in his 1953 dystopian novel Fahrenheit 451, ‘something we can’t imagine, to make a woman stay in a burning house; there must be something there. You don’t stay for nothing.’

On Ulva, a 12-kilometre stretch off the west coast of Mull, with L. we encountered packs of red deer, spotted white-tailed eagles swimming above the sea, we found ticks crawling over the dog but no humans. Ulva was emptied during the Highland Clearances of the 18th and 19th Centuries, when landlords evicted tenants in favour of sheep farming. By 1889, the population of Ulva dropped from over 600 to 53 people, to 30 in 1991 and to 11 in 2011. Since 2018, the island is community-owned, an endeavour launched to increase its demography, which now sits at 16 residents, and to boost the economy while preserving the island’s environment and heritage.

Then there is Gometra, which appears to an outsider like me as the little sister of Ulva, at the western end of the moorland. The two islands are connected by a short foot bridge. At the honesty shop on Gometra, I found four peppers and a handwritten note next to them that said ‘Ready for a good home :)’, so I packed the vegetables in my backpack, left some coins in the jar in exchange of three carrots and two candles, and I exited the stone-wall gallery to meet Ludo and Leopoldo outside. We walked back to the bothy by following the coastline, the eternal islander’s compass, finding large jellyfish washed off on the black rocks, pungent as they decomposed, picking pebbles and following the tracks of oystercatchers as we heard empty crab claws crush under the sole of our hiking boots, sleepy seals under the brewing heavens. We kept roaming until we caught the melody of a freshwater stream and spotted a small woodland ahead. If I knew that heat moves upwards, I guessed that a fire goes faster uphill, so we headed upstream too, hopeful to find wild garlic to season our tuna and pepper pasta. It was Easter Sunday, and we were in the mood for lunch.

Start the fire and bring water to the boil. In a bowl, mix semolina and water and form a dough. As we are making orecchiette, this one needs to feel stretchy; olive oil will help. Let the dough rest underneath an upside down bowl. In the meantime, roughly chop the wild garlic and set the garlic over the fire with a generous amount of oil. In foil, wrap halved (heart removed) peppers and place them near the fire to roast. Return to the dough, divide it in four and make logs. Cut small bits, about 2-3-cm long each, then shape balls between the palm of your hands. With the help of a knife, curl the dough over the tip of the knife. Pull the dough off, push one finger inside and turn it inside out. Repeat – the pasta should look like small ears (kind of). Return to the fire and chop the peppers. Mix the peppers and a can of tuna with the garlic; stir. Once the water is boiling, salt and cook the orecchiette. Drain the pasta and combine with the sauce.

‘These violent delights have violent ends

And in their triump die, like fire and powder

Which, as they kiss, consume.’

– Romeo and Juliette, William Shakespeare

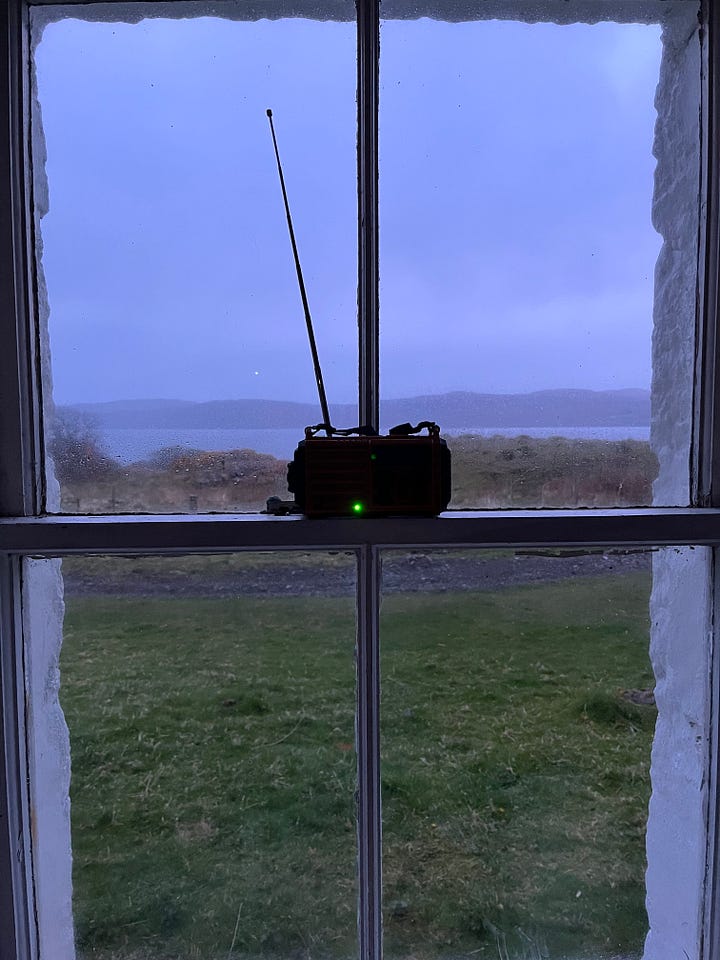

Evenings inside the bothy were my favourite hours, earnest by the candlelight, my old and reliable solar-powered radio grizzling on the windowsill. The end of days carried an aftertaste of tiredness too, from fighting the winds and rain showers, hiking through bushy heather fields and boggy grasslands, cutting dead and drifting wood into logs for the next fire. No time tracker nor weather updates; no network, only the life cycle of that one fire, scorching then cold, reviving it from its ashes, choosing to start again rather than to repeat the same course of actions mindlessly. A fire is a complex combustion indeed, something joyous and chaotic, vivid, complex; sparkling, dangerous for how much it could give and steal.

As I sat next to the warming and compound wood burning stove inside the bothy, I found it impossible not to think of the fires that are weaponised against the land and its habitants, of the ceasefires we demand. The urgency for those ceasefire treaties to be honoured beyond signature. The prayers for lives to be protected against human-induced raging flames. I thought about wildfires too, and the devastating effects they have on the land’s biodiversity and the quality of the air that allows for life to thrive on Earth. According to The Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS), the global emissions due to wildfires reached 1,940 megatonnes of carbon monoxide in 2024. That same year, the US National Interagency Fire Center recorded 61,685 fires, which burned 8,851,142 acres. While it wasn’t the most devastating year on record, Earth has seen wildfires intensifying with strength and frequency due to extreme weather patterns powered by climate change.

Firelighters, kindling, logs; bring water to the boil. In a pot, pour in a tin of ratatouille and season with paprika, salt and pepper. Leave to cook. Add a can of chickpeas (with some of the water preserved) and cook. Lay some foil over the stove and warm up the pita bread. Eat.

If flames lead an impressive and sensorial show, it is the invisible particles a fire spreads in the air, and leaves behind, that are most dangerous: most mortalities caused by fire are down to smoke inhalation. It is quick and discreet – looming as another day passes – to be consumed by the pursuit of a fabricated purpose, looking for something greater than what the present holds. As I searched for dead wood, trimmed the logs, got a fire started then waited for the water to bubble, being careful not to suffocate L. and the puppy with the smoke I had provoked, I found a form of focus I had lost. Not sheltered, not impossible to disrupt but aware, malleable with my surroundings – set to complete a task but indecisive about the method as, once you have used all the water in the kettle, you have no other choice than to wait for another long while before more water will boil.

A good forager will research the ambient flora and study the nature of the soil before seeking out mushrooms as there isn’t one insatiable purpose but plenty of small, purposeful acts stitching up the web that threads our cultures, both outwardly and inwardly. A serious birdwatcher knows to listen before taking their binoculars out as one’s purpose can be obvious, as much as it can be disguised, be shared or individual, plural, long-term, instant. Communities don’t evolve at the same pace; being remote doesn’t mean being out of touch. Seasons, death and life, and life and death, are a chain of actions and reactions and, whether you befriend your spirits or not, please note that if I say to knock on wood for good luck, it is because I believe that some spirits do live inside trees.

A final tip for you: in France, you may touch your head if you don’t have any wood near you. Knock wood, knock your head; perhaps the secret of happiness hides in remembering that we have agency over the movement(s) we initiate.

It is getting hot. Look after each other, until next time,

margaux

thank you for reading The Onion Papers. i’m margaux, a writer and cook, and this is my hybrid newsletter. if you enjoy my work, remember to subscribe and/or invite friends to the party as you keep me going.

Thursdays are for long reads and Mondays are for annotated (unmeasured) recipes (to paid subscribers), both come out every other weeks. Peels, a writer’s almanac, go to all subscribers on the first Monday of the month. O, I write novels too.

Alone in the Kitchen

If the water has boiled, my body is still warming up, rinsing and chopping unpeeled vegetables, crushing the garlic clove and halving the onion. Mix everything together, lower the heat, leave the casserole alone, skimming off the foam occasionally. The simmering of a broth is a form of meditation I trust. Its preparation follows a chain of steps and eac…

I adored this. Cannot believe you MADE orecchiette in those circumstances. What an adventure!