Undoing the Reader’s Journal

on reading in 2024 and (bits on) Roland Barthes; a late reader and multilingual approach; some books

If you’ve gone through the French education system, you may associate being taught and shamed as reciprocal. (This is my observation, and I don’t endorse the method; I wouldn’t know if this is still the case as I left France years ago.) The point is, when I was in collège, so the mandatory school years between 11 years old and the age of 15, we had to undergo weekly French tests. The first one happened in front of the class: one of us was picked, seemingly randomly, first thing in the morning, and asked to head to the chalkboard to write the conjugation tables for three given verbs, one from the 1st group (i.e. finishing in –er), one from the 2nd group (i.e. finishing in –ir) and one from the 3rd group (i.e. finishing in –ir, –oir or –re). The other students sat in silence in the meantime. A second student was chosen to head to the front of the room to correct their classmate, then the professor gave them a grade on the spot. The other test was a dictée. Grab a blank sheet of paper; the professor walks up and down the classroom and reads from a novel or philosophy book at talking speed; you must transcribe the extract as they speak. You will then be evaluated on the accuracy of what you wrote, your orthography and your syntax. The maximum number of points you can retain is 20, with each mistake bringing you down (in my time, it was -0.5 for a syntactical error whereas an orthographic error would cost a full point), Yes, you can fall beyond the minuses, like I did. Between a chronic condition that affected the mobility of my jaw and my elocution, as well as learning needs the educational system didn’t accommodate, I was a late reader and often muted. I fell behind, redid a year, still didn’t get a chance to fall in love with either reading or writing.

Eventually, I graduated, moved out of France, and found my own way into becoming a reader and a writer. It was a learning curve, a consequential process affected by more factors than I could have anticipated or could possibly summarise here, but it had to do with giving up on the French language for some time which, at that moment in my life, meant seeking freedom elsewhere. It was an exercise in distancing rather than othering – the ‘don’t text me for a while’ stage of a bittersweet break-up. I started seeing new possibilities in meaning then, not by teaching myself but by reading in languages for which I only had a basic knowledge, or others I didn’t even know. The aim wasn’t to become fluent in all those languages but to tenderise grammar. You could say that I was still young, to which I would agree; I hadn’t seen much else than the north skirt of Paris, but I couldn’t find myself there. Everything felt rapid and harsh, cutting me mid-sentence when I couldn’t find the words to chip in; I needed the words I used to be fluider than talking speed, not inked as lastingly as written pages, so I would be able to figure out who I was first, then introduce myself to others. There was no expectation for me to ‘get it’ with those languages – to relate and to be relatable – not like the native and fluent readers in that — their — language would be. I also told no-one; I was in transit. Concretely, I became good at stopping mid-sentence to check a dictionary, spell a word to myself and fall down a rabbit hole of etymologies and cultural histories, to digress and to return by a process of association and dissociation. I learnt to read aimlessly and to trust the sentence.

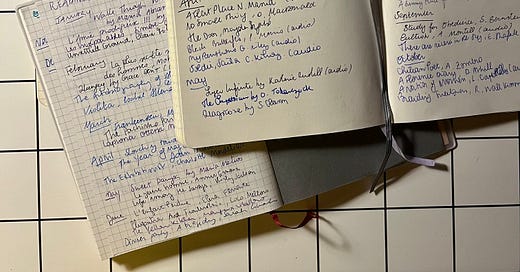

In 2024, I returned to that reading method, or lack thereof, loosening my preconceptions about what language can/should do and reversing to a quest for what I make of language. Every year, I keep a list of all the books I read, scribbling each title over the last two pages of my paper diary, but I don’t record the unfinished books which are, in all honesty, those I read the most. What follows in this newsletter isn’t a definitive list of what I read or my ‘favourite’ books of the year as I, for one, am too stubborn to complete such an exercise. Secondly, it is my view that good criticism is far too moveable to be compound to a definitive, numbered list as I regard the temporality factor as the most important variable.

Kate Briggs, who translated two volumes of the French philosopher Roland Barthes’ seminars and lectures, is also the author of a book I return to often: This Little Art. My last experience sitting down with it was a few weeks ago and tentative; I didn’t know what I was looking for, but I knew that it had to do with how I anticipated certain texts as I had unexpectedly felt conflicted by an old favourite. I found the answer in the early pages, when Briggs reminded me that, when Barthes gave his inaugural lecture as the Chair of Literary Semiology at the Collège de France1 on 7th January 1977, he chose to speak about Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain. Barthes specified that he had re-read the novel recently, for another seminar, and he claimed to have realised that the Tuberculosis he had experienced as a young man couldn’t have been the treatable variant of the disease that was going around in the seventies (The Magic Mountain is set before World War I). To re-read the novel had made, in his words, his body ‘historical’. Less elegantly put, I would say that Barthes felt old. He then said: ‘I must fling myself into the illusion that I am contemporary with the young bodies present before me.’ To read is to confront foreign bodies, in time and experience, with ours.

I am predictable and now listening to the audiobook of The Magic Mountain for the first time. As I type this, I am about six hours into the thirty-six-hour-long recording. It’s too early for me to articulate proper thoughts about the novel, other than to say that I never had Tuberculosis, but I have visited many hospitals in my life, enough to know the bonds we create there are both radical and frivolous. That is to say, I followed Barthes to this sanatorium, somewhere in the Swiss Alps, but upon arrival I began building my own relationship with Mann’s word and the characters he shaped, through the English translation as well2. Relatedly and unlike Barthes, who died in 1980, this year, I also read Olga Tokarczuk’s The Empusium (translated from the Polish), for which Mann’s novel was listed as an inspiration, and I respected the breath of that novel deeply. As I finished it, it was evident to me to re-read Jean Paul Sartre's existentialist play, No Exit (1944), which is about three deceased characters who are punished by being locked into a room together for eternity. I flicked through the same copy as the one I had started annotating in school. The reader is an ageing body. Reading is a debate of influences, sometimes rallying and, at other times, clashing – a bubble waiting to be burst.

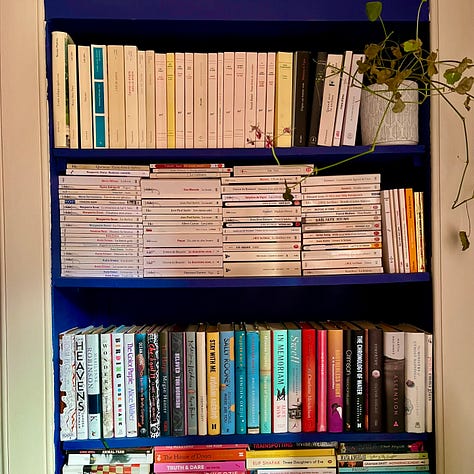

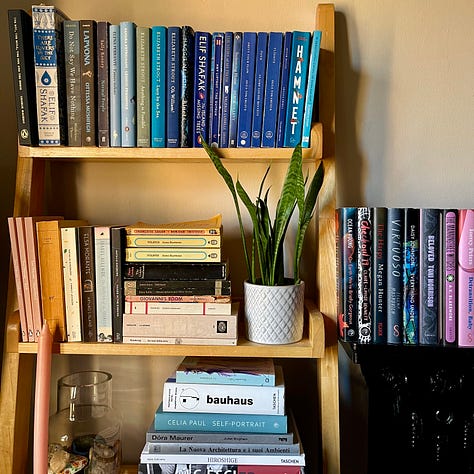

But a familiar bubble is a reassuring order; seemingly relatable and validating. I dedicate most of my reading time to returning to passages from books I am trying to get to know well, or to re-reading classics of mine. This year, I spent an awful amount of time with the tragedians. 2024 was a solitary one for me – I sought space and time on my own, trying to unlearn systems around productivity, creativity and money I had normalised through my previous lifestyle and as a capitalist-trained citizen of this world, so I could settle into life changes that were necessary to my well-being. I settled into a new city, changed jobs and treatments, trialled new rituals (and refused the routine). It felt endless and terrifying at times, liberating and exhilarating at others, then calm and, when human nature chased me, the everyday shrunk again. I grew bored of going around the same block of flats, so I indulged into the circles of hell by reading Dante’s Divine Comedy in Italian but side by side with a recent French translation by Danièle Robert. I reconciled my relationship with power figures by re-reading Athalie by Jean Race, Medusa by Euripides, Lucrèce Borgia by Victor Hugo. My usual and beloved names haunted my bedside table all year long, acting as both reminders of where I had come from and safety nets – Carson, Duras, Lispector, Morante, Morrison and Woolf.

Equally, the canon is dangerous. I am holding myself accountable not to turn this newsletter into an essay about Roland Barthes as this email isn’t the form and now isn’t the time for me to do that, but there is one in the works. The point, for now, is that as much as I read Barthes, I also think he was guilty of gatekeeping when he spoke about the French language and divided language and style as objects, versus writing as a function. Around those points, Barthes also concentrated on authors such as Daudet, Maupassant, Proust, Zola for chapters so, while I am thinking through his work as a critical framework, I don’t see it as a representative source.

Famously, Roland Barthes claimed that ‘language is never innocent’. This quote has been narrowed down by severe abridgements, and the word ‘innocent’ isn’t giving Barthes a fair voice in the English language either. A sense of time passing may still be hinted at, but that concept was central to Barthes’ point – when Barthes reminds us that words have a secondary memory, which is projected through new significations as they are written and read again, he is holding language holders accountable in their own time. To be with words come with duty; it isn’t a passive choice or a right to take for granted. We remember through language, otherwise we are bound to a silent agreement with History; words are manipulative tools and we are manipulative with words and manipulated by other words’ holders. Returning to Barthes’ quote, he then summarises his point by saying that to write is to compromise between freedom and memory. Reciprocally, I would add that to read is to be confronted with a compromising exercise, between what we would like to be told and what we are shown. To that end, this year I was taken by surprise by some novels that showed me corners of the world I couldn’t have foreseen on my own: The House of the Spirits by Isabel Allende, Hagstone by Sinéad Gleeson, Enter Ghost by Isabella Hammad, Pachinko by Min Jin Lee, Black Butterflies by Priscillia Morris and Minor Detail by Adania Shibli.

When I step into a public library or stand in front of my bookshelves, I ask myself if I want to be comforted or confronted by my next read. I don’t think that one or the other is ‘better’ or ‘more important’, but each principle answers different questions and such an awareness will matter when I will want to articulate an opinion about the text.

I often think about Xiaolu Guo’s A Concise Chinese-English Dictionary for Lovers. She wrote:

‘One day I find a poetry by William Shakespeare on school’s library shelf. I studying hard. I even not stopping for lunch. I open little Concise Dictionary more 40 times checking new words. After looking some Shakespeare poetry, I will can return back my China home, teaching everyone about Shakespeare. […]

One thing, even Shakespeare write bad English. For example, he says ‘Where go thou?’. If I speak like that Mrs Margaret will tell me wrongly. Also I finding poem of him call ‘An Outcry Upon Opportunity’:

‘Tis though that execut’st the traitor’s treason;

Though sett’st the wolf where he the lamb may getI not understand at all. What this ‘’tis’, ‘execut’st’ and ‘sett’st’? Shakeaspere can writing that, my spelling not too bad then.’

I came to Xiaolu Guo’s writing via my book club, when we read Once Upon a Time in the East together, which remains one of my favourite memoirs. This prompts me to say that, this year again, my most nurturing discoveries were recommendations from friends. Not always for the book itself but for the words we exchanged afterwards, between us, agreeing and disagreeing, extending our references further away than at arm’s length, having to look beyond ourselves and what we had known together. To read is also to learn to disagree through a slower process than refusal. To fall out of agreement and perhaps, on some occasions, to be proven wrong, or to accept a new kind of truth.

Recommendations from friends included: Constructing a Nervous System by Margo Jefferson, Beyond Black by Hilary Mantel, Accabadora by Michela Murgia, The Door by Magda Szabó.

I was challenged, too, by how much I wanted to comprehend the horrors of our humanities, therefore I hunted for authors who put words on them. Hungry for What by María Bastarós (translated from the Spanish), Lanark by Alasdair Gray, A Sunny Place for Shady People by Mariana Enríquez (translated from the Spanish), Le Musée du silence by Yôko Ogawa (translated from the Japanese).

I didn’t read either. I stopped, for weeks.

When I refused to read, I worried I might never read again. Like I didn’t before. I read plenty of brilliant writers on how to read, compulsively, with essays and newsletters by Alexander Chee and Lydia Davis and Brian Dillon and Susan Sontag and Brandon Taylor. They stimulated my thinking but didn’t fix my reading. The latter is my responsibility.

I tried to read about taking notes but, if this newsletter wasn’t a demonstration of my affections already, I gave up on the structure and practice rapidly. I don’t like writing notes about a book anywhere, other than inside the said book, in situ. If you lend me a book, I will return it annotated (consider yourself warned).

If language is a maze, reading is like algebra – a solvable problem with reason. Like a recipe. One ingredient after the other, one sentence after the other, only cooking fixes not knowing how to cook; only reading fixes not reading. Breaking the spell, one word after the other, sometimes a full sentence, sometimes a paragraph, until the window breaks open, unsealed – a new world.

‘The pleasure of the text is that moment when my body pursues its own ideas—for my body does not have the same ideas as I do.’

— The Pleasure of the Text by Roland Barthes

As I had done before, I cured my fear of being floored by a novel with a specific non-fiction book — The Green Ages by Annette Kehnel, translated from German by Gesche Ipsen. This is a broad history rather than an opinion piece, which uses examples from high to late Middle Ages in common living and sustainability to demonstrate that civilisations have always known highs and progress. After years of working hard to reach ‘modernity’, we are now suffering from a collective fear of change, othering how others live(d) as a form of self-(re)assurance. I didn’t subscribe to all the ideas in the book but, as always, I was reminded why I love to read historians: they apply data to the patience of a storyteller. And, when 2024 slipped away from me, us, rolling simply too fast with opinions and radical movements, at gunfire and hurricane speeds, I couldn’t help but think that we collectively have something to learn from that mindset.

It was a good year for non-fiction overall. Some of us just Fall by Polly Atkin, Storm Pegs by Jen Hadfield, The Outrun by Amy Liptrot, A Flat Place by Noreen Masud, Super Infinite by Katherine Rundell, Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer.

I read plenty other things than books as well. Messages from friends, good and bad emails, packaging information, signposts, subtitles on screens. I read over the shoulder of strangers on trains. I studied many political pamphlets, manifestos from political parties and independent candidates ahead of elections, some for which I could vote and others for which I couldn’t vote. I read letters from the NHS, captions on social media. A lot of newsletters, not as many articles as I would like to say I did. I read menus. I read for work, not only for leisure and, sometimes, I confused one another, which resulted in me being frustrated at reading. Perhaps to read is like falling in love, heartfelt in principle, quite the headache in reality.

As I pick one of my last read(s) for 2024, I can share two truths about my reading journey with you:

When I feel stuck, it is reading that loosens me. When I feel stuck, it is reading I find hardest.

Margaux

PS. what have you been reading this year? we could all use more pals’ recommendations.

PPS. books are great gifts, making someone happy in your life and an author happier.

*Most of the books referenced in this newsletter are listed in TOP’s affiliated bookshop.org. For transparency, I receive a small commission if you purchase a book through it, which doesn’t impact the author’s earnings.

The Collège de France is not to be confused with the collège (secondary school). This is a higher education and research institution located in Paris. Anyone can attend lectures and seminars, which are free and cover both humanities and science disciplines.

The Magic Mountain was first published in German in 1924. If you’re curious about the Mann case, then I also recommend Colm Toíbin’s fictionalised novel of Thomas Mann’s life: The Magician.

Thank you for reading. I’m Margaux, a writer and cook, and this is my hybrid newsletter. If you enjoy The Onion Papers, you can subscribe and come back for seconds (Thursdays are for long reads and Mondays for annotated recipes, both come out every other weeks) <3

A thoughtful meditation to counterbalance the season's book lists. Thank you.