Time Fantasies

on relative temporalities and, in a fever dream, on healing; Bachmann, Beckett, Morrison, Pessoa and breadmaking

When I entered the bakery, a man welcomed me warmly. Robert wore a cap, whose colour had faded under a thick layer of flour, and quickly I realised that he would round each one of his sentences by saying ‘if that makes sense’. Robert runs Narture, a bakery, creative and social enterprise located in Ayr (a town located on the southwest coast of Scotland), and I had come with L. to attend a breadmaking course. As for Robert, he had the task of condensing the forty-eight-plus-hour process of making sourdough bread into a three-hour workshop.

He explained that we were going to reverse the baking process, starting from the last step (shaping a dough for baking) and working our way back towards mixing flour and water to make a new sourdough culture. Fine, in principle, and rendered possible by our setting, as we were inside a bakery that had plenty of starter available and loaves at various baking stages to experiment with. We set forth –

Robert staged this intermittent process by sharing facts about bread with us. He spoke about the production of flour, the individual histories behind scoring a dough, the connection between society and wheat cultures, artmaking with bread. He – it, the temporality of the day he was hosting for us – made perfect sense to me. Robert personified the bread-maker, a reminder that whoever we think we are, which space we ought to occupy in this world, regardless of our means and context, ultimately the fulfilment of one’s hunger relies on pre-existing systems, either natural or constructed by predecessors, that stretch far beyond our personal remits. And that each one of our doings, or non-doings, or un-doings, feed and/or starve these systems.

‘I am writing with my burnt hand about the nature of fire.’

― Ingeborg Bachmann

After the workshop, I caught myself (re)watching videos of En Attendant Godot (the first performance was in 1953), Samuel Beckett’s tragicomedy in two acts, which features Vladimir and Estragon as they wait for Godot. We don’t know who Godot is and Godot will never come. The famous play has been widely reviewed as a metaphor for the futility of one’s existence, for which salvation is expected to come from an external entity, always. Something of a nihilist idea, it’s been said to be about the absurdity of life. Watching the play again now, I reached a rather simple conclusion: it’s a text about waiting, as written on the cover. And, taking the thought further, a lot of modern life is spent waiting. I wondered how the play would be structured if it had been written as our contemporary, if rather than waiting next to a tree, chatting to one another, Vladimir and Estragon would have been waiting in a busy café, a pub, or at a train station, scrolling down their phones, absorbing news but not talking about the news. I wondered if they’d be silent, but vocally silent, the way the performance of mass media entertains.

En Attendant Godot, Waiting for Godot, is as much about waiting as it is about the lack of introspection. I gathered that, if Vladimir and Estragon waited for that long, it’s because to move on would force them to contemplate a potential return, thus summon them to confront the memory of an event versus the reality of the said event. There, then is when a linear temporality reaches its limitation – one can never move on fully, past and future constantly cohabit, in a whirlwind called humanity.

‘If a house burns down, it's gone, but the place–the picture of it–stays, and not just in my remory, but out there, in the world. What I remember is a picture floating around out there outside my head. I mean, even if I don't think if, even if I die, the picture of what I did, or knew, or saw is still out there.’

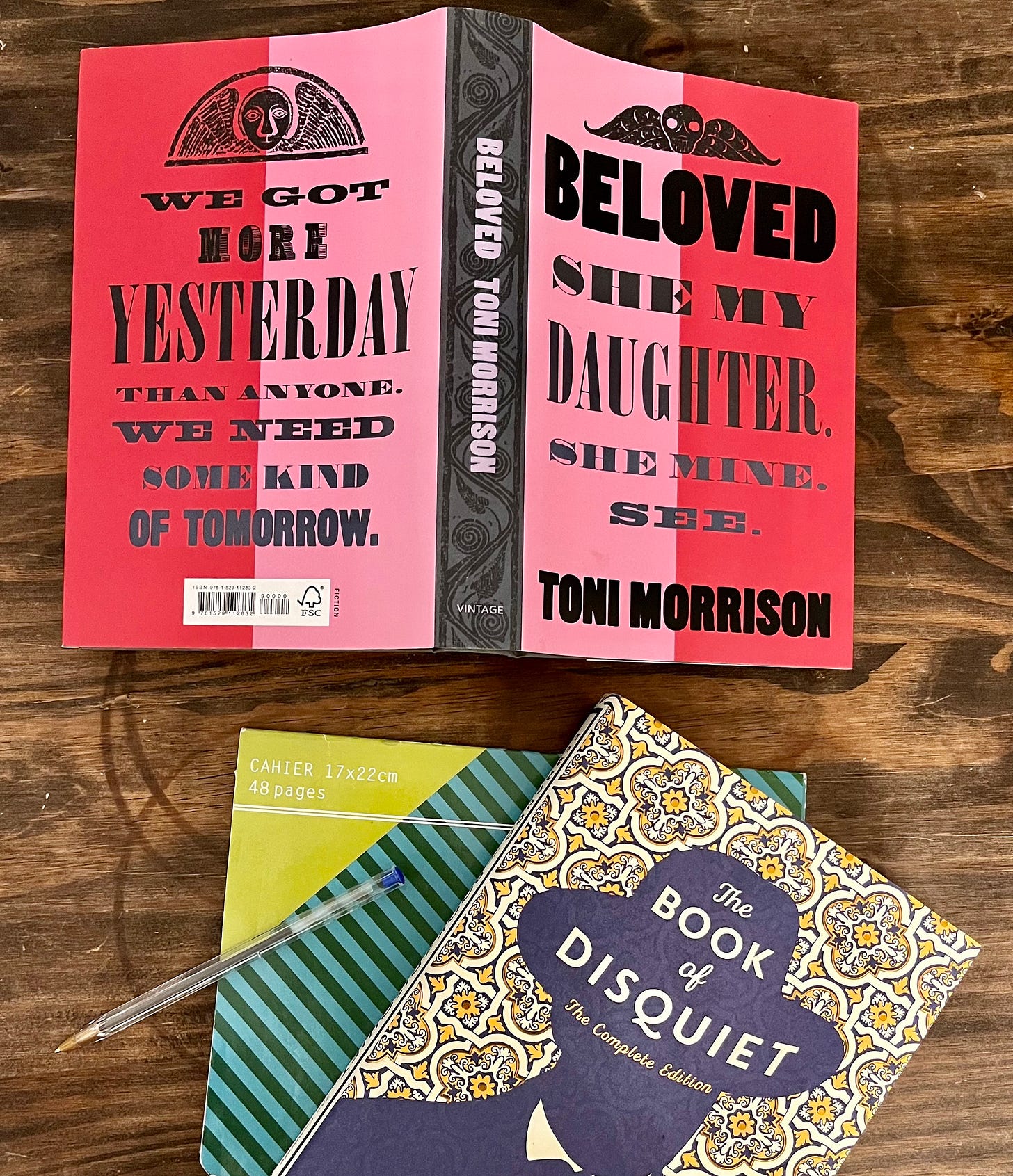

— Beloved by Toni Morrison

Allow me to reference one of my favourite novels, as in books I find the strength to articulate my ideas: Beloved by Toni Morrison, which was inspired by the life of Margaret Garner, who escaped from slavery in Kentucky, with her family, in 1856. When US Marshals apprehended her and her children under the Fugitive Slave Act, Garner killed her daughter so she would never be enslaved again. Morrison’s Beloved is a novel that deals with the haunting aftermaths of (a) traumatic event(s). The book recounts the life of Sethe, from her days as a slave in Kentucky before the Civil War, to her present as a free woman in Cincinnati, Ohio. Sethe lives with her teenage daughter, Denver, in a house she shares with the spectre of her dead child and whose tombstone is etched with the word 'Beloved'.

There is a lot to say about Beloved (and I’ll include some links below, if you’re interested to read more about the novel and Morrison’s work), but since today I’m looking at nonlinear plotting as an allegory for human experiences, I’m interested in looking at how the novel is narrated. It isn’t chronological: Beloved gravitates and bounces back between flashbacks, memories, and nightmares. Whether the scenes are ‘real’ or ‘unreal’ doesn’t matter – they bear witness, as much as the bodies and minds that embody them do.

Talking about Beloved, Morrison said that, at the time of her writing, slave stories weren’t inclusive of women, and she had wanted to change that. In an article published in The New York Times on publication, in 1987, Toni Morrison explained that she ‘didn’t do any more research at all about the story.’ And that she was driven by a ‘Desire to Invent.’

Time in a novel is informed by the author and the narrative decisions they make; time in society is orchestrated by our actions, as far as our own privileges go, and by structural authorities. Still, the two realms obey to the same rule, in that time will crumble under the appeal of one’s memory – and that it’ll lose against the intransigence of death. So, perhaps the question isn’t about me-you-us anymore, but it’s about how we want time to play out for our shared cause as humans because, as basic as this may sound, our actions have roots that precede us, and will carry on long after us. From the most mundane of gestures (anyone who has shared a flat with someone else, who commutes, will know) to the bigger, global picture.

inspired by the soundtrack of All of Us Strangers (a movie directed by Andrew Haigh, 2023)

Storytelling and cooking are two vectors for social representations – they’re projections, trajectories of where life can lead and withdraw, lived examples that truths shine through the nonlinear passage of time. That we can cohabit with our ghosts only if we’re able to name them.

‘Everything around me is evaporating. My whole life, my memories, my imagination and its contents, my personality - it's all evaporating. I continuously feel that I was someone else, that I felt something else, that I thought something else. What I'm attending here is a show with another set. And the show I'm attending is myself’

— The Book of Disquiet by Fernando Pessoa

Time is always ahead of us, so what are we making of yesterday?

writing, relaying, telling

writing images; showing by writing

archiving, memorising

Margaux

further reading:

Extract from The Source of Self-Regard: Selected Essays, Speeches, and Meditations by Toni Morrison – on writing Beloved;

Toni Morrison’s Research Notes for Beloved via Notes by

(substack);Toni Morrison, interviewed for The Art of Fiction No.134 at The Paris Review;

Toni Morrison’s Nobel Prize lecture;

Links to the books referenced in this newsletter (via TOP affiliated Bookshop.org): Waiting for Godot by Samuel Beckett (I haven’t read the English translation, but I’ve read that there are some alterations); The Book of Disquiet by Fernando Pessoa; Beloved by Toni Morrison;

Something to eat? I shared a recipe for a radicchio risotto on Monday (for paid subscribers), or you can head to TOP Pantry.

Thank you for reading. The Onion Papers is a reader-supported publication. If you enjoy my work, you can support what I do by upgrading to a paid subscription. You’ll get access to the full archive and weekly entries. It costs £4 per month, or £40 a year, and you can unsubscribe at any time. No pressure: I’m happy you’re here either way.