The Silence Within

on differentiating aloneness from loneliness; a personal farewell to Alice Munro, spinach gnocchi to cook

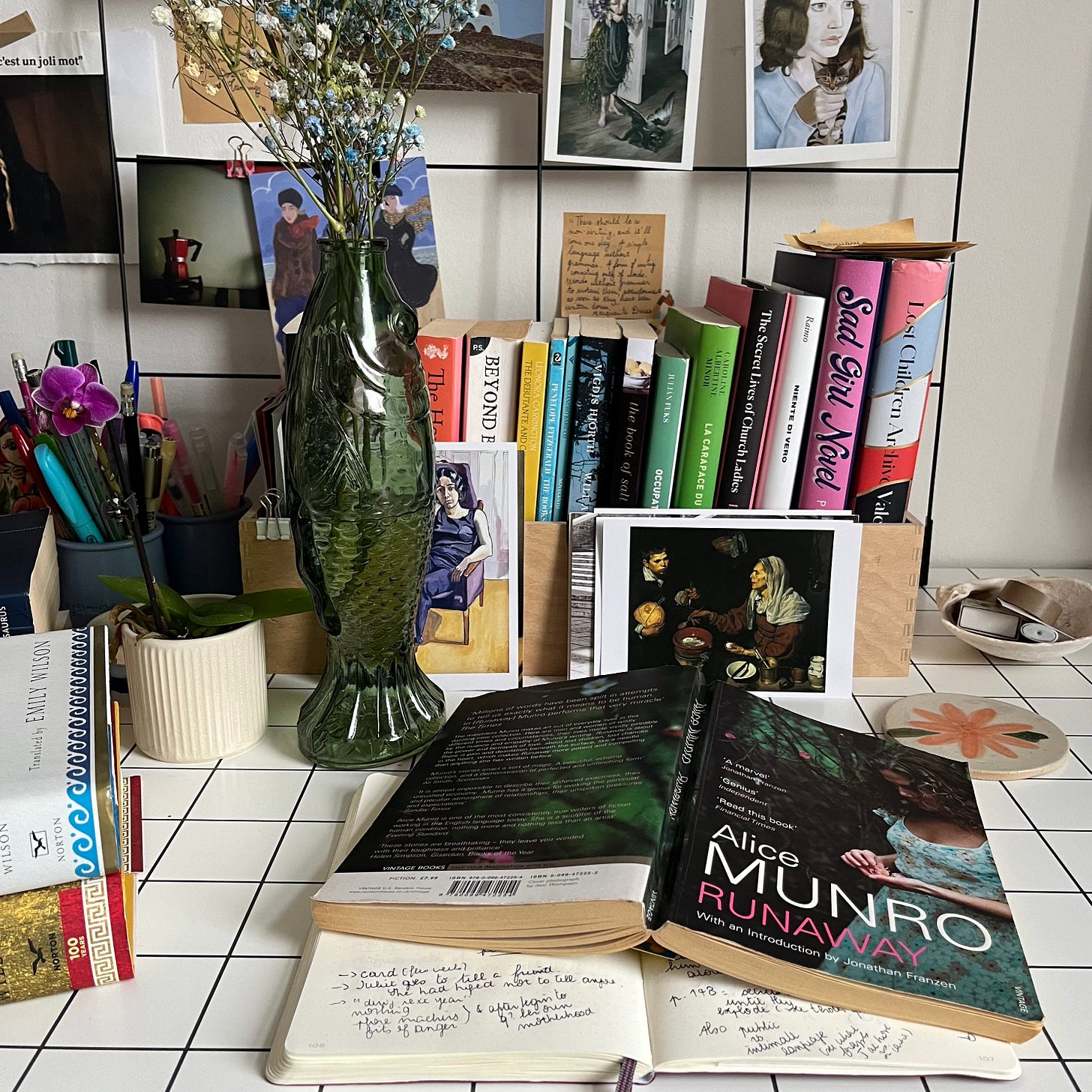

On 13th May 2024, short story writer and 2013 Nobel Prize for Literature winner, Alice Munro, died in Port Hope, Canada. Munro is the first author I remember reading in the English language. It was 2014 and I was at the library on the campus of the Université de Montréal – and I panicked. I was highlighting words, reading the same paragraph over and again, scrolling up and down an empty Word document on my laptop; I only had a few days left before my essay was due. The problem was I couldn’t make sense of Munro’s sentences. If I isolated the words – ‘exasperated’, ‘cubicles’, ‘hectically’ – I knew their definitions, the letters plain enough and often close in sound to my mother tongue, yet they didn’t hold together. I was flirting with a new language, feeling both brave and defensive, interrogative about the meaning behind what I could see happening and over-thinking what I had thought to be happening. But forasmuch as I dug for a greater sense, I silenced Munro’s writing; I was an impatient reader, wordily with my worries, speaking over the characters in the story.

I don’t remember how it ended for me in that class, but I felt the urge to return to the story after hearing the news about Munro’s death. It’s called ‘Silence’ and it appeared in the New Yorker in 2004 as well as in Munro’s collection Runaway (published in 2004 in America and in 2005 in the UK).

‘Silence’ is the story of Juliet, who was estranged from her daughter, Penelope. Readers of Alice Munro will remember Juliet from previous stories, including her affair with Eric, who is Penelope’s father. ‘Silence’ opens with Juliet travelling to Denman Bay to pick-up Penelope, aged 20 years old and who was attending a spiritual retreat there. We learn that it was the longest time Juliet and Penelope had ever been apart, and soon we’ll come to realise that Juliet will never see her daughter again. The head of the retreat tells Juliet that Penelope is nowhere to be found – she adds: ‘Juliet, I must tell you that your daughter has known loneliness. She has known unhappiness.’ Juliet returns home and the story develops through Munro’s skill to move backward and forward in time, giving us hints about the past the two women shared and the things they never told one another. Juliet waits to hear from Penelope, who sends her a birthday card the first year – ‘It was the sort of card you send to an acquaintance whose tastes you cannot guess.’ – and eventually, after five years, communication will stop altogether. Juliet will love again and fall out of love once more, grieve for friends, bump into a childhood friend of Penelope who will reveal having seen Penelope recently and unexpectedly, handing Juliet a precious insight about her daughter’s adult life, until Juliet will find a certain peace. Munro writes: ‘The Penelope Juliet sought was gone.’

I’d like to tell you about ‘Silence’ without spoiling the story for you. It shines in the details that hide through nuances and the waiting that spirals alongside memories and re-memories – or, as Munro puts it: ‘You know, we always fear the idea that there is this reason or that reason and we keep trying to find out reasons.’

The absence of a reason is what I couldn’t accept when I read ‘Silence’ for the first time as a student. I don’t think that I wanted more from the story per se, but that, at this stage in my life, being insecure about my identity and my choice to have moved to Canada, I couldn’t accept that the conclusion I had reached from my reading was enough. That a good story about a mother being estranged from their daughter didn’t need to explain the daughter’s decision. I didn’t trust myself to have read Munro properly because surely, I thought, Munro would have justified the character she had fleshed out with her pen. Surely, all absence must be justified, right?

Yet, Munro didn’t justify Penelope. And yet ‘Silence’ is a powerful story about absence and the long-lasting, quiet effects of trauma sinking into a lifetime. I can’t begin to imagine what it feels for a mother to be estranged from their child, but I know how I’ve felt as a daughter being estranged from a parent. It’s a harsh and resilient pain, like rust slowly decaying a pipe. It holds, flowing clean water through, until it breaks, spoiled water pouring in.

Re-reading ‘Silence’ at this stage in my life, a little older and intimate with the English language, the message I took away is the same as the one I often hear myself think when I’m standing in the kitchen: silence isn’t solely the absence of noise, but the wait we hold against ourselves. Silence is waiting to be heard, silence is not being safe enough to speak, silence is bracing ourselves to do the thing we want to do, silence is being restricted or restricting ourselves, silence is underlying trauma patching past and present in the shadow of our public selves – to be silenced is to be emptied.

Water boils, the gas flame or the beeping alarm of a wet induction hob, chopping vegetables, oil sizzling inside a pan and other domestic dramas: it’s never quiet in the kitchen. It requires attention to hear the silence within us, or a certain peace with the outside world and how we think it mirrors our existence. Going back to ‘Silence’, Munro ends the story as follows: ‘She [Juliet] keeps on hoping for a word from Penelope, but not in a strenuous way. She hopes as people who know better hope for undeserved blessings, spontaneous remissions, things of that sort.’

The story of Juliet and Penelope, as told by Alice Munro, finishes with the two sentences quoted above, and I step away hoping that Penelope has moved on from ‘knowing loneliness’ to finding her aloneness. I see Juliet mature and alone, back to her first love for the ‘old Greeks’; I can’t say if she is happy, but she feels truthful and at ease with herself. I also hope you’ll get to read the story and enjoy it as much as I do.

For now, you may gather 80g of fresh spinach and 50g of pasta flour (00).

While I can’t claim that I have a remedy against feeling lonely, I can testify that teaching myself to be alone in the kitchen has helped me greatly over the years. It still does, and whenever I’m asked to recommend a dish to spend time with oneself in the kitchen, my answer is gnocchi. Regardless of how you make yours – with potatoes, squash, polenta – the portions are malleable enough to feel generous for one but not wasteful.

Bring water to the boil and cook the spinach for five minutes. Drain and dry well with the help of a kitchen towel. Chop the spinach.

In a bowl, combine the spinach and the flour. Add salt and a drizzle of olive oil. Prepare a small glass with lukewarm water, keeping it next to you. Begin kneading, working the mixture into a homogenous dough. You can add lukewarm water as you go to help the dough hold together. Only one pinch at a time; you don’t want the dough to become wet or sticky. Make a ball, cover with a kitchen towel and leave it to rest for 20 minutes.

On a working surface, cut the dough in half and make logs. Slice each log into 1-1.5cm square bits. Slide each one of them over the tip of a fork or against a gnocchi paddle, if you’ve one. Don’t worry too much about appearance: you only need to find them appetising. I’d only recommend making them the same size, so they’ll cook homogeneously. Cook the gnocchi in salted, boiling water until they float to the surface.

Last week, I served these spinach gnocchi with fish ragù.

This recipe works wonders when the body is fatigued but the mind is restless. There aren’t many steps to follow but a long simmer to wait along.

Margaux

PS. If you enjoy this newsletter, feel free to forward it to a friend, or two.

further reading:

The Art of Fiction No.137, an interview with Alice Munro for The Paris Review; this article by one of Munro’s French translators, about Munro’s temporality (in French); Munro’s obituary in The New York Times.

Watch Alice Munro talk about her work here. This is the pre-recorded interview she gave instead of a lecture at the Nobel Prize reception in 2013.

On the topic of silence, last year I wrote another newsletter and it included a recipe for gnocchi di Polenta:

*Breaststrokes, my second novel, is available at your favourite bookshop, or I’ve listed some options here. Thank you for reading.

Greate peace, love it, look forward to read Alice Munro (^-^)

oh i love your analysis on this, runaway is one of my all time favourite story collections too