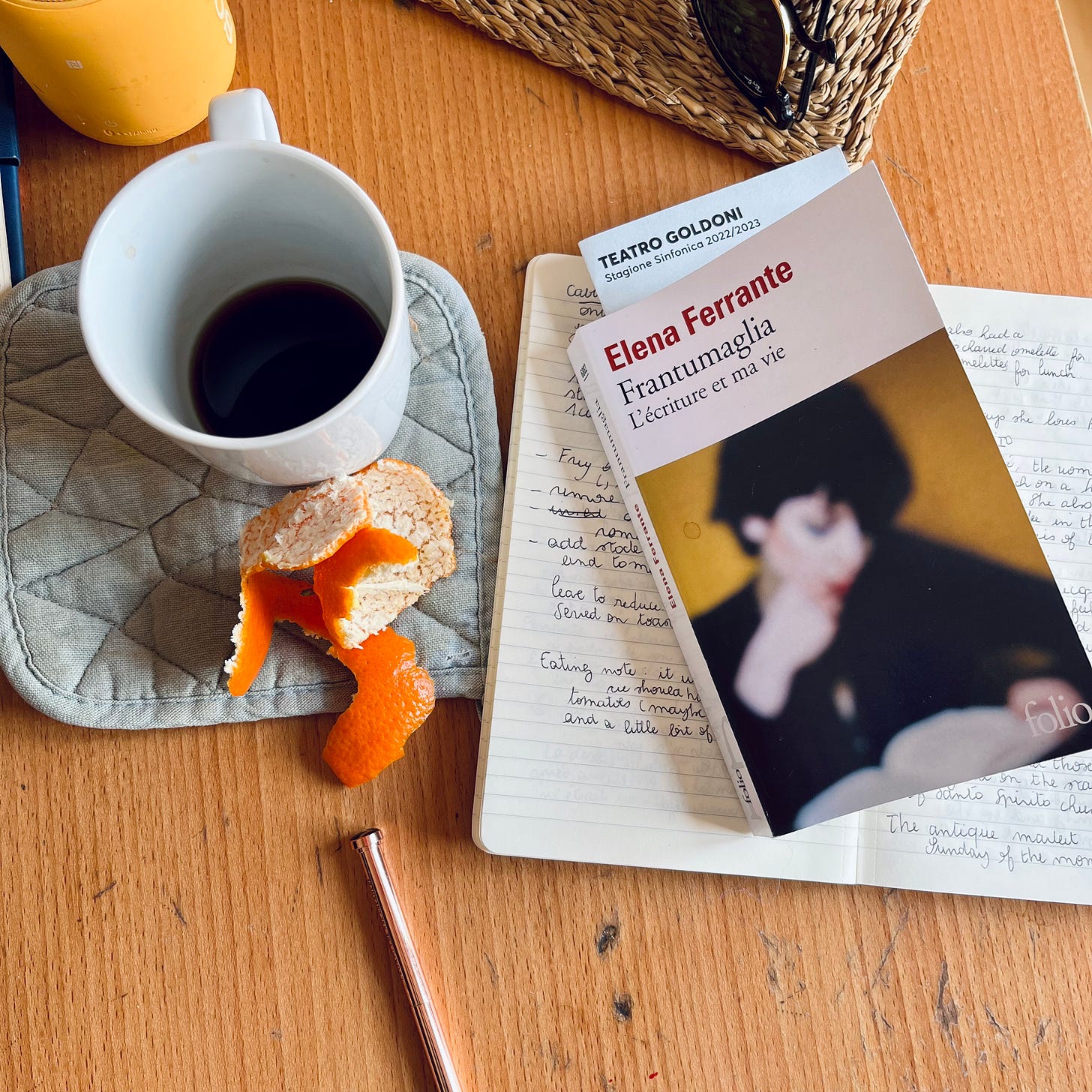

This edition of The Onion Papers started with a trip to the laundrette. Only books that are composed with short paragraphs or chapters are suitable for reading in this blinding, loud environment, so last week I picked both my dirty laundry and Elena Ferrante’s Frantumaglia: A Writer’s Journey. I’m putting this newsletter in context because my inclination to write about silence isn’t recent, however the broadness of the topic has made me hesitant. As someone who pursues silence as a medium to think and as a communication tool I trust, I didn’t want to bruise my relationship with silent language.

Allow me to start with Frantumaglia, Ferrante’s collection of correspondences, interviews and unpublished book extracts that cover a period from 1991 to 2016. The letters I found most fascinating are the ones sent between Elena Ferrante and film director Mario Martone about the adaptation of Ferrante’s debut novel, Troubling Love, for the cinema. Not only the methodology with which the originating author (of the novel) and the second writer (of the script) delve into each other’s approach of the text – such as the use of a voice over or spoken versus shown argumentative rhetoric – is a masterclass in characterisation, their dialogue demonstrates the challenge of associating written words with spoken language. From one letter on to the next one, a trust agreement arises between two authors who produce and receive linguistic signs: ‘Dear Martone’ becomes ‘Dear Mario’, and Ferrante admits that the script grants (her) words with a new meaning. ‘I have been happy to work on your text and to imagine what could it benefit from: I have sometimes felt like I was reworking mine,’ Ferrante signs off her final comments to Martone. Exactly there, the silence I’m talking about sits. Between what is said and not said, a space for interpretation, a language of one’s own.

Many theories about the momentum effect and the construction of language in our society have been published, and while I won’t pretend to be a wise linguist, it’s important to acknowledge that I’m differentiating a chosen silence from being silenced. Being silenced hurts and nurtures unequal, unsafe, punitive settings whereas the silence of one’s own can be an active form of language – a conductor of signs. When I was researching this newsletter, I came across a scientific paper about eloquent silences between oncologists and patients that illustrate the crux of this difference. By looking at ‘connectional’ silences between doctors and patients with the help of musical and lexical analysis, researchers show the benefit silence can add to the complex choreography between listening and being heard. A qualitative silence isn’t a silence that halts nor a response to being shut down, but the marker of an inclusive tempo – a breath.

In a contemporary world where societies are built around networks of citizens, silence disrupts and disturbs. It’s reviewed as ‘awkward’ or as a proof that something isn’t right; it’s said to be weak not to speak up, disengaged. Yet, there is a gap between the standardisation of language and the evolution of society in which such a language is performed. Think of the perception of accents and the unwelcoming academic and literary spheres for anyone who doesn’t tick the expected boxes on admission forms; name Rishi Sunak and his government for blocking Scotland’s gender recognition legislation; remember when the French Academy warned about the ‘peril’ of French language around discussions of feminising its grammar back in 2017. Language introduces assumptions and classifies inequalities: who shouts the loudest has authority and silence is confined to the language of intimacies. I regret this because, in my experience, eloquent silence enables conversations.

This is also the story of a young girl who doesn’t sleep well but loves bedtime because it’s when she can lie awake in the dark and tell herself tales. It’s a silent movie of girlhood, an intimate theatre played for no-one to see, a personal lexicon in development. The same girl goes through recurring episodes of mutism during the years. She grows into a woman who learns to negotiate her speech with instances of eloquent silence, as follows: a respectful pause then speaking back at someone, pondering; sitting in a corner (preferably on the floor) with noise cancelling headphones, not playing anything, seeking; refusing to respond to someone, either in writing or in speaking, an empowering treatment (justified or not); touching lips close instead of saying ‘I know’, smiling to love. Eloquent silence is a form of self-control of the semantic – it’s the unspoken ‘I’ in the shadow of the everyday cacophony societal systems orchestrate.

I was the girl, I’m the woman and when I’m cooking, talking and writing, I dedicate most of the process to figuring out what it is that I’m thinking. I don’t start with questioning the form, nor the texture or the shape of an idea, but the stitches that link ideas and thoughts; I search for the linguistics of that idea, a vector to convey thoughts outward. I’m admittedly too melancholic not to give silence a meaning: empathy; silence is an empathic language that accommodates self-doubt and misunderstandings to make connections.

In writing, the poetic of silence transpires too. The craft of silence – its metaphors and ellipses for examples – was the beating heart of Ferrante and Martone’s epistolary exchange to transpose Troubling Love from pages that were written to be read, on to words that will be spoken on a screen. To my knowledge, they never exchanged out loud either. In cooking, silence speaks through gestures that replace words (frying up a garlic clove in its skin so it can be removed before the dish is served to a friend who doesn’t digest garlic), or ingredients replace inhibiting sentences (throwing a sprig of rosemary into the pan for maman). The kitchen stands for the buoyant room where one can make something in silence: the grammar is one of peeling, chopping, frying. The vocabulary consorts with odours and, hopefully, its punctuation will taste delicious – the dictionary of the domestic kitchen is kind.

When I actively seek silence in the kitchen, I knead dough. My hands keep busy enough to forget that I feel helpless before the world; there, I can hear myself think. Between my two sourdough starters and my appetite for a good savoury tart at lunchtime, I have entertained silence in my kitchen consistently over the years. Until recently, when the absurdity of the UK rental market drove me to live out of a suitcase and in short-term accommodations. I’m grateful that my work allows me to do so and that I’m able to afford this lifestyle, however this also means that I’ve had to reconsider the significance of silence in my quotidian.

There are two factors for my state of silence in translation: the first one is purely linguistic. We’ve been staying in Italy, a country whose national language is my partner’s mother tongue. Italian is a language I now understand well enough to be frustrated when I share a meal with friends: my comprehension is greater than the level of elaborated sentences I can construct. This makes me braver than I was in the past, so I launch myself into descriptions and arguments that I need to detail with hand gestures and sound effects, or with an eloquent silence that relies on the empathy of my interlocutor. This has reminded me that I own my silence less when I’m insecure with spoken words. Secondly, I gave away my sourdough starters because they are sedentary beasts who fear change of temperatures and humidity. We haven’t stayed in one flat with a working oven, and the top of a small fridge is the sole working surface. I cannot knead nor bake therefore I keep on learning, a process, while I listen to my appetite. It’s taken me a few weeks, but last Sunday I flirted with a new kneading language that only requires a pan, a recycled pot noodle container and a teaspoon: gnocchi di polenta.

This is a recipe for fantastic gnocchi that will translate into any language. I served mine with radicchio because it needed to be eaten, but I would recommend serving them with something saucier (mushroom ragù?).

Instant polenta

00 flour

Radicchio, roughly chopped

Balsamic vinegar

Garlic clove, crushed, whole and unpeeled

A sprig of rosemary

Walnuts, thinly chopped

Parmesan, grated

Olive oil

S&P

Start with making the polenta. The ratio is 4 portions of water for 1 portion of polenta. The kitchen isn’t well equipped here so I used a recycled cup of instant pot noodle for proportions, as follows: in a large pan, pour in four cups of water and bring to the boil. Stand next to the pan with a wooden spoon and a cup filled with polenta. Turn the heat down and start pouring the polenta slowly, mixing constantly. Once you’ve poured all the polenta, do the same with the flour (about three quarters of the pot noodle cup – you’re looking at a thick texture). Turn off the heat and leave aside.

In a separate pan, heat up some oil with a sprig of rosemary and one garlic clove. Add the radicchio and cook until the vegetable is brown and has reduced. Remove the garlic and rosemary and add a spoon of balsamic vinegar to reduce the acidity, as well as walnuts, salt and pepper to taste. Reduce the heat to the lowest, simmer.

In the meantime, prepare the gnocchi. Pour some cold water into the cup and keep it close to you. Spoon some polenta like you’d do with ice-cream and make some inelegant (but pleasing) gnocchi. Drop the spoon in water between each gnocco to help with stickiness. Don’t worry too much about the form, they will taste the same either way; make the gnocchi, and plate with the radicchio for cushion underneath.

The last letter from Ferrante to Martone as published in Frantumaglia was written after Elena Ferrante went to see the movie based on Troubling Love for the first time (L’amore molesto, 1995). It’s indicated that the letter wasn’t finished nor posted: ‘It was saying something he already knew,’ Ferrante explains in a later interview that also features in Frantumaglia. Elena Ferrante’s decision not to send this recognition note to Mario Martone – her choice not to reopen their dialogue that happened behind the scenes – moved me deeply. This one stands for the consuming effect of silence, a cautious approach to language not to betray a personal lexicon, because it’s often easier to lie than not to say anything.

‘Her sociability irritated me: she went shopping and got to know shopkeepers with whom in ten years I had exchanged no more than a word or two; she took walks through the city with casual acquaintances; she became friends of my friends, and told them stories of her life, the same ones over an over. I, with her, could only be self-contained and insincere.’

– Delia on her mother, from the first chapter of Troubling Love: A Novel by Elena Ferrante (2006)

I take a mouthful of easy-knead gnocchi in favour of a silence. Hush, listen. It’s melting in my mouth.

Margaux

PS. Talking of cinema and books, this week I enjoyed Brandon Taylor’s newsletter ‘the miserly eye’, a craft talk about cinematic fiction.

In other news:

Your description of silence as 'the unspoken ‘I’ in the shadow of the everyday cacophony societal systems orchestrate' is one of the most perfect things I've read. Thank you for this.

Gorgeous piece.