Movable Spiders

on practice; Louise Bourgeois; nesting, and a new recipe for madeleines

Did you gasp when you saw it? Trapped inside the sink, first thing in the morning as you poured yourself a glass of cold water. Or did you open the window swiftly, without making a fuss after you spotted it hanging at the corner of the curtain? I know, that one was imposing – as large as your hand! – as it crawled through the living room mid-episode of Slow Horses. It’s mating season in the UK and spiders have come out of their hidden corners, looking for a match to prosper and revealing their existence in plain sight.

The trees were still puffy with leaves when I last stepped inside the Novecento Museum in Florence. I had come to see ‘Do Not Abandon Me’, an exhibition of some of Louise Bourgeois’ sculptures and gouaches, which gravitate around the themes of motherhood and abandonment. Louise Bourgeois was a Franco-American artist, best known for her sculptures, (monumental) installations and paintings. While I’ve written about Bourgeois before and why, as a writer, archivist and linguist, I’m indebted to Louise Bourgeois—the artist who mended psychoanalysis with art-making—it was my first time seeing her gouaches exposed on this scale.

For context, the Museo del Novecento focuses on art from the 20th and 21st Centuries and was established inside a square-shaped, Renaissance-style building that used to be a hospital before becoming the Spedale of the Leopoldine, a public school funded in the 18th Century to give free education to under-privilege girls. Nowadays, modern art is staged with columns and religious demonstrations, bursts, portraits of Saints and colourful stained-glass windows, the light playful and bearing witness as past and present hold hands. Such a setting is one of the reasons why I love to visit the Novecento: the building’s architecture and the curator are in conversation; one couldn't be present without the mirror effect of the other one.

This past September, as I entered the Novecento, I was confronted with Spider Couple, from Bourgeois’ spider series, as the sculpture was exposed predominantly inside the courtyard. The vision echoed Bourgeois’ widely known Maman (1999), a thirty-foot-tall single spider cast in bronze, marble, and stainless steel. In this (rare) case though, there were two spiders coupled together, as if they were hugging. Were they? I doubted as I approached the installation, and I began pondering if one was dominating the other, if one was on the run and the other settling in.

Then, I spotted a spider within the spiders.

Louise Bourgeois associated spiders with her mother, Josephine Fauriaux, an artisan who restored fragile tapestries and who had formed Bourgeois to the practice of weaving early in life. She had trained her daughter to help in the family workshop. While Mother died of an unknown illness when Louise Bourgeois was only twenty-one years old, the artist didn’t forget the skills she had learnt from her mother — and they would metamorphose into new forms, such as casting and stuffing, as well as to expand, stretching to Bourgeois’ individual art practice.

‘With the spider, I try to put across the power and the personality of the modest animal. Modest as it is, it is very definite and it is indestructible. It is not about the animal itself, but my relation to it. It establishes the fact that the spider is my mother, believe it or not.’

— Louise Bourgeois

Needless to say that Louise Bourgeois’ relationship with her mother and psychoanalysis is far too complex for me to pretend that I could approach the topic here and now diligently. Not that I would be interested to know more either; Louise Bourgeois and Josephine Fauriaux had their intimacy and that is none of my business. What I’m inquiring is the fracture between the image and the experience of the mother (and, one could add, motherhood), and how the metaphor of the spider works as a common thread through generations.

Over the years, from a curious interest to a certain kinship, I’ve grown familiar with Louise Bourgeois’ spiders, but I learnt little about spiders. And, you see, I like to hold onto a fact, data, something whenever I’m feeling helpless. If you do too, you might wish to know that spiders create their web with silk, a natural fibre made of protein, which they draw through spinnerets on their abdomen. At the end of which, there is a nozzle-like structure, through which a single silk thread comes out of them. The silk is liquid when it’s inside the spider.

Most species then follow various patterns to construct their webs, which suit their environment, hunting and breeding habits, just like one would switch coat for the new season. Spiders are nurturing and lethal. My research has taught me that spiders have excellent survival instinct and, since, I interpret catching eyes with a spider as a good sign.

LB, as she signed most of her tapestries and some of her drawings, also reckoned in spiders for their process – in building architectures of the bodies, complex structures sourced and solidified on traumas, psyche, memories and expectations. Of ‘non-dits’, taboo, as Bourgeois is also the artist who switched between French and English midsentence, always committed to interdisciplinarity.

‘Since the fears of the past were connected with the functions of the body, they reappear through the body. For me, sculpture is the body. My body is my sculpture.’

— Louise Bourgeois

The truth is, I had felt awkward as I walked past people photographing the sculpture from afar, as I got closer to this object that had been transported to Florence to be exhibited. A work of art. But I couldn’t stop myself, so I committed to being careful when I lifted my right leg and slid between the legs of one of the spiders, then as I tucked my body softly underneath the second spider’s belly, and I felt them close to me. I would have never spotted the spider within the mother spiders otherwise, not if I hadn’t surrendered to them and let them harbour me. I was seen too.

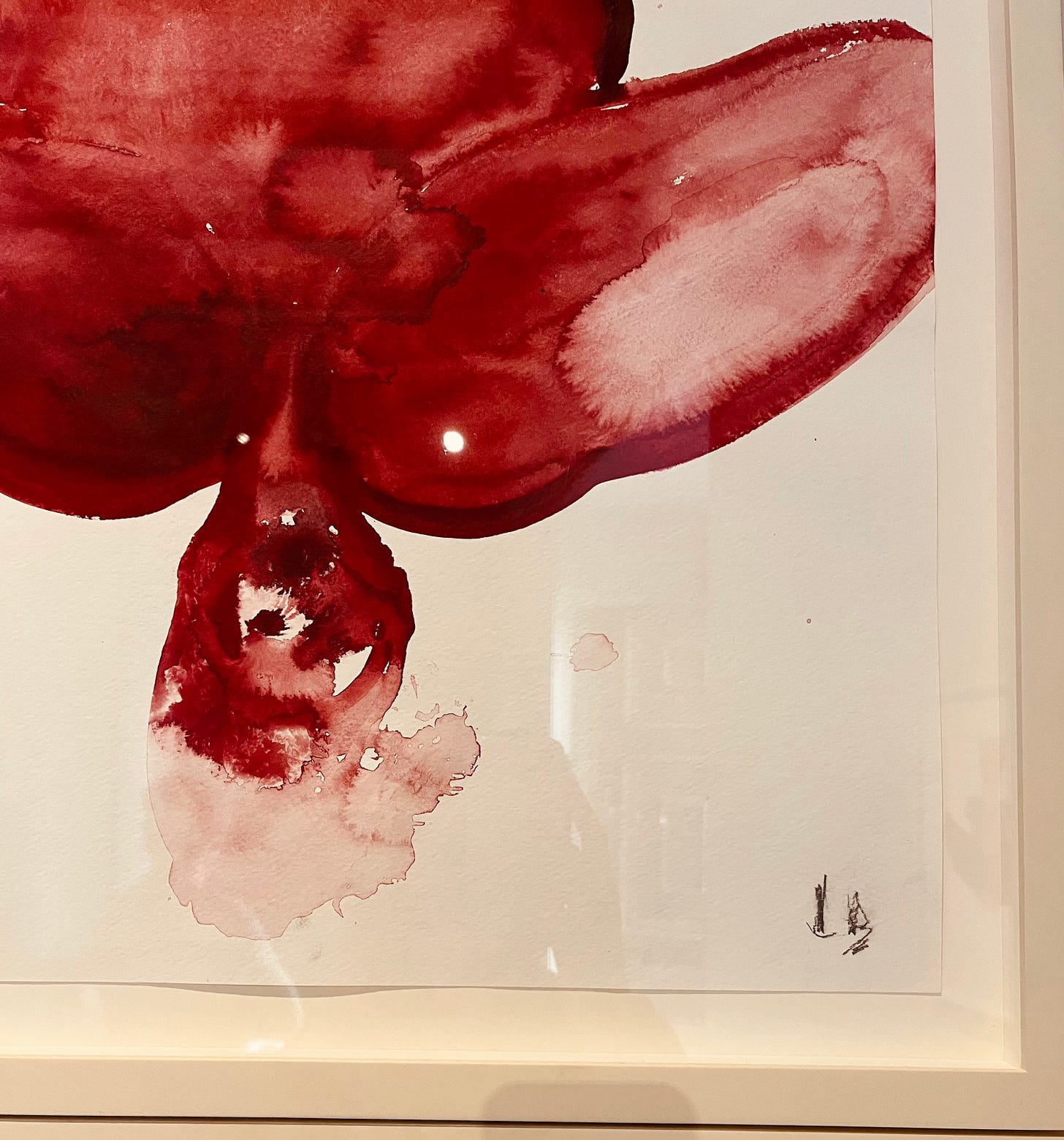

The second part of the exhibition was visceral. It focused on Louise Bourgeois’ red gouaches series, which she initiated in the late summer of 2007, three years before her death. Her method for those was to work ‘wet on wet’, so the gouaches would soak the paper and spread out over it, and she repeated, until the drawings, once made of defining lines, bled and gained an embryonic quality to them. LB described the process as one of gestation and nurture, something from within, a practice she had earned for herself by letting go, as she surrendered to fate and luck after years of intense psychoanalysis.

Bourgeois also spoke about red as the colour of blood and emotional intensity. Her gouaches, which feature breasts, foetuses, flowers and/or cells and genitals are furious indeed, as if the objects were drawn from their own blood, like a nightmare that can be thought of but not remembered well. They feel jealous and distressed and confident at the same time. They can be displayed timelessly across the walls of a museum, stick figures and cursive letters, childlike, yet depicting sexual scenes contemporaries would classify as ‘adult content’. They are trauma laid out on a sheet of paper. They’re effective—one colour, one format, on repeat—and they show our common nature before we nurture. One experience—to have had a mother—and one loss—to lose a mother—with shady variations—‘Everyone who has had a mother, has lost a mother,’ as LB said.

To me, they are body-like, universal and subjective at once.

‘My art is a form of restoration in terms of my feelings to myself and others.’

— Louise Bourgeois

As I returned to Glasgow, the trees were trimming, the remaining leaves the colour of an egg yolk and the soil wet, and I found more spiders inside my flat than I had ever done before. There is nothing magical or deep about this though, simply the fact that I have been living between places, packing and unpacking, moving dust and homes, unrooting the spiders they had held.

Before returning the keys of one of the two flats to the letting agency, I removed frame hooks and applied plaster over the holes they left behind, bleached the bathroom and scrubbed the kitchen, mopped the floors and vacuumed the carpets. I cleaned the windows, then I walked around the empty flat one last time. I knew I had forgotten something; my yellow wellies were squashed in the corner of the entrance cupboard. As I bent my knees to grab them, I noticed a spider had nested inside the left boot. It was a giant one as well. It’s not the spider that scared me though, but the thought that I could have inserted my foot inside the shoe and crushed the spider’s rigid body under the sole of my foot. Shiver. I opened the window, and the spider flew away, going with the wind. And I drew in a long breath, chilling.

Later on, at the new flat, it took a few trials before I understood how the guillotine windows work. I climbed on the kitchen counter, so I could use the strength of my shoulders fully, pulling the window from above. The latch gave in, so I toyed with it, using a screwdriver, then I tried to open it again, still in the same position but more gently this time. The pressure released, the window slid upwards, and the breeze came in — polished, antique copper, both nostalgic and rejuvenating, an autumnal rainfall.

I sat still for the first time in days, cosy between the sink and the yellow wall of my new kitchen and out of sight from the moving boxes. I had been fidgety, disoriented amidst another rapid yet seemingly never-ending move, my fifth address in two years. Every time I saw a chip on the door or each time I drilled a new hole in the wall, or when I repainted the bathroom, there was a kick in my stomach. As if to say – eh, I was here before. The silenced architecture of the lives of those who had lived here before me shadowed my movements and thoughts, heavy and sticky like a wet sleeve. And there she was: a spider nesting at the corner of the windowsill. She was impressive, hairy with long legs, angled so that she could protect her eggs, weaving tenacious webs into a home of her own. I sat still for longer, watching her, and she didn’t budge as we did.

Some mornings, I can see the spider as I open the window in the kitchen, but most often I feel anxious as I can’t find her. This is when I started to research how a spider threads a web of its own and discovered that not all spiders make webs; less than 37 spider families found in Britain do.

As for now, I painted a corner of the kitchen in red and settled my desk over there. I baked another batch of Louise Bourgeois’ madeleines* and untangled some words, here in this flat, a spiderweb of existences.

Margaux

*My original recipe for madeleines was dedicated to Louise Bourgeois’ insomnia and more faithful to the traditional, French recipe (available here). This week, in search of new processes, I’ve worked on a new recipe for Madeleines. This one is citrusy and dairy free, and I hope you’ll enjoy it.

50g brown sugar

zest and juice of 1 lemon

pinch of salt

2 eggs

10g yeast

50g flour (I use 00)

100g ground almonds

50 ml almond milk

In a bowl, combine the sugar, lemon juice and zest and the eggs with the help of a whisk. Add a pinch of salt and give it another mix.

In a separate bowl, combine the flour, ground almonds and yeast. Then slowly incorporate the flours into the wet mixture, mixing continuously. Add the almond milk and keep mixing until you’ll have a homogeneous preparation.

Cover with a kitchen towel and leave aside for 1 hour.

Preheat the oven to 180C. Prepare a madeleines-shaped oven dish by drizzling some olive oil on top and spoon some of the mixture inside each one of the moulds. Bake for 8-10 minutes or until golden.

The madeleines will preserve well in a sealed food container.

Thank you for reading. If you enjoy this newsletter, feel free to forward it to a friend, or to share it with two:

If you’ve been forwarded this email and enjoyed it, you can:

firstly, HOW have you written an entire essay about something i hate (spiders) and left me feeling full?!?!? secondly, obsessed with the fact that your new kitchen has a yellow wall !!!!

All my spiders are called Reg at home and I greet them when I see them — has done wonders to the irrational fear