Merenda: On Deserving

snacks and thoughts between poll stations; reflections on power structures and ‘norms’

A slice of white bread, with an overnight crunch, softened by a drizzle of olive oil. Perhaps a pinch of salt? Or slice a tomato and brush its flesh against the bread crust – with a definitive pinch of salt and black pepper. A slice of salami or prosciutto, if grandma were doing the school pick-up. To contest the slice of cured meat instead of chewing it would be an option, but grandma would advise to rejoice at the sight of meat for merenda instead. Tomorrow she could be spreading the leftovers from dinner in the panino – and we both know that she would. She looked harsh, rigid in her one-piece dress and a shawl wrapped around her neck, until she spoke about sprinkling sugar over a slice of bread, which she dipped in wine, pinching her lips in an expression that may be a smile in disguise.

merenda, noun [feminine] / me'rɛnda

snack

By etymology – coming from the Latin ‘merere’, meaning to deserve – to have a merenda is something to deserve. However, as French, structuralist philosopher and semiotician Roland Barthes would put it: ‘the book creates meaning, the meaning creates life.’ Structuralism, according to Barthes, is a theory that conceives cultural phenomena as sign systems that operate under rules, which are ingrained in structures deeper than surface appearance might lead to believe. As such, when an individual sign might feel, or be indeed, arbitrary, it cannot be comprehended wholly outside of a system of signs either. Something came before and something else will come after.

Historically, working men in fields and factories across Italy popularised merenda as the art of snacking we enjoy today. Still, the word rose to a contemporary meaning in line with its roots – workers would be ‘deserving of’ a snack (bread and prosciutto often) after an early start and long shift. Nowadays, children are offered a merenda upon returning from school; they may also obtain more leverage to choose what type of snack they will eat if they were good pupils.

There is nothing new with such a power dynamic: ‘the carrot or the stick’

As a food writer, I am interested in the links between food cultures and social prejudices, from the right to access food to the unequal division of labour and enjoyment powered by food systems, as well as the misinformation and health hazards promoted by diet culture. With that in mind, if Barthes’ structuralist school puts an emphasis on how meaning is created rather than on the actual meaning, to query how we share resources as a society – therefore who deserves to eat – helps to bridge the gap between the two poles.

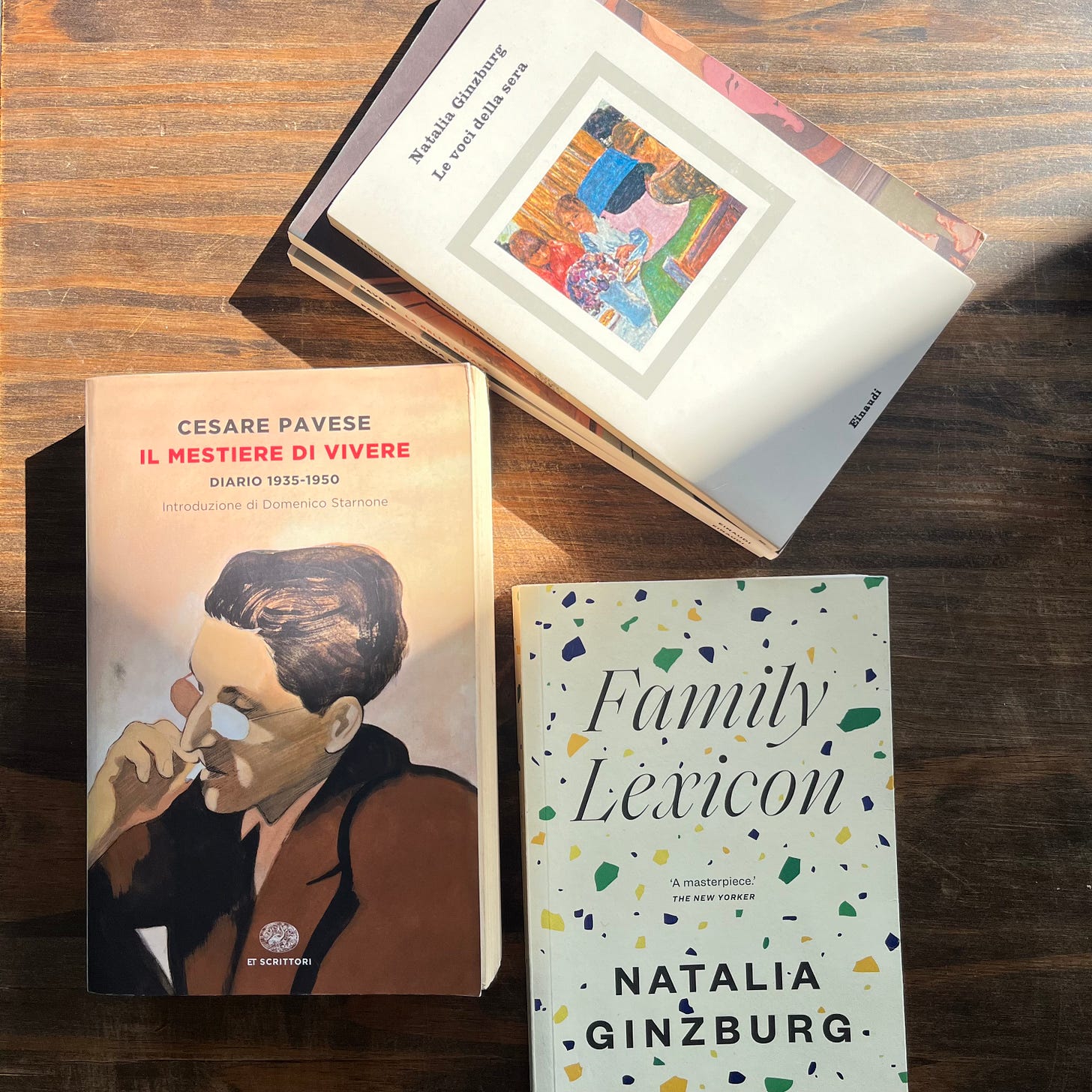

One of my favourite paragraphs ever written in literature is one I would call a merenda extract. It was penned by Italian activist and writer Natalia Ginzburg, about fellow Italian writer and friend, Cesare Pavese:

‘That spring Pavese often arrived at our place eating cherries. He loved the first cherries, the ones that were small and watery, and he’d say they “tasted like heaven”. From the window, we’d see him appear at the end of the street, tall, with his swift stride, eating cherries and spitting the pits against the walls, his shots lightning-fast and exact. For me, the fall of France would forever be associated with those cherries which, when Pavese arrived, he made us all try, pulling them one by one from his pocket with his parsimonious and grumpy hand.’

— Family Lexicon by Natalia Ginzburg

The above extract follows Ginzburg’s memory of spending her spring evenings with Rognetta and Pavese, who ‘hated goodbyes’. On that night, Ginzburg tells us, he had said goodbye like he wouldn’t see her anytime soon, which was as ever: ‘grumpily holding out only two of his fingers.’ It was World War II, Italy was under fascism and Mussolini, following Germany’s invasion of Belgium, had also declared war a few days before. It won’t be until 2nd June 1946, when an institutional referendum was held, that a Republic would be voted in Italy. Reading on Family Lexicon, I can tell you that Ginzburg will return to Pavese’s cherries in later pages, in an homage to her friend after his suicide at the end of the fruit’s season, on 27th August 1950.

If Pavese’s cherries are Ginzburg’s image of the fall of France, to me they have become the sign of two single-minded thinkers who associated in friendship at a time of political hardship and censorship. That is to say, the food we eat and share, as much as the food we can’t eat and don’t share, is never uncoincidental from our circumstance(s), present and future. Food structures, from production to consumption, are riddled with disciplinary signs such as fictitious seasonality, rigid calorie counts and table manners that reinforce a form of subjection to an otherwise invisible power structure – a link between our physical bodies and our internal subjectivity. The food creates meaning, meaning creates life, to echo Barthes.

At an age of endless comparison and examination, at a time when money, the mythologies of beauty and happiness have been objectified and are cast as interconnected measures for success, to approach appetite as a tryptic for human rights, health factor and pleasure is relevant to political and social discourses. The decomplexified way eating has been turned into a privilege, from land privatisation to the expense of ingredients, the mass-production and uberization of food distributions, all the way to the interlinked philosophies of indulgence and richness, encapsulates modern mechanisms of control. Food institutions are built to promote docility and compliance – they control how we eat and how we perceive food, from lack to waste, all the way to normalising sentences such as ‘deserving to eat’. Whether the authority is about having enough money or having physically exercised enough to access the food you like to eat, the equation is the same. Subjugate so you can be granted benefits.

As someone who shares how I eat on social media routinely; as a woman who writes about illness, sexuality and the ecologies of the body and the mind; as a freelancer, constantly on the hunt for work, while having my political views and my writing subject to reviews and the judgement of others, I spend a lot of time thinking (read: worrying) about the self-elected, omniscient mirroring lens in our society. About the rapidity at which we form opinions, through the bounce back of looking at the image of ourselves inside the body of someone else we hold accountable for ‘the norm’.

‘What I claim is to live to the full the contradiction of my time, which may well make sarcasm the condition of truth.’

— Mythologies by Roland Barthes

2024 is a year of elections – waves after waves. Looking at the most recent examples, and those about which I can talk from direct experience, there was the European Parliament earlier in June, the French legislative elections will begin at the end of the month and the UK general elections are scheduled for the 4th of July. My immigration status doesn’t allow me to vote for the latter but as someone who lives and works in the UK, I am equally exposed to politicians’ disciplinary discourses and subjected to the power structures their ‘parties’ defend. Only two weeks ago, as I was watching an interactive map of France tuned in with the colour of far-right politics on my phone screen with horror, I was reminded of similar maps showing Covid infection rates back in 2020 – about an epidemic, something that was gaining us, frightening our individuality and numbing us as a collective. But I am not proud of the image.

It is a dangerous analogy to compare power structures with an epidemic because the same power structures commonly use the metaphor to create and punish the figure of the misfit. In other words, anyone who doesn’t fit with ‘established social norms’ must be ‘disciplined’ so they can be ‘rehabilitated’, therefore become compliant to existing power structures and reciprocate them. In return, power figures become the reference and the personification of social norms.

‘But what does it mean, the plague? It’s life, that’s all,’ as Albert Camus showed us with his novel The Plague.

In the simplest of honesty, I think that it is fair to say most of us are tired. And it weighs me to write the sentence, but it is again on us friends to unite and roll up our sleeves to show that we disagree. That while it is primordial to agree to disagree for a plural society to function and to find an equilibrium, it is not possible to reach an inclusive society until we have cracked some basic rights such as the right to live and to die in dignity regardless of where we were born, how we live and the paths we choose to pursue. That is, pick your Merenda and please go to vote. Our future is deserving of us. And we are deserving of our future.

Margaux

PS. If you enjoy this newsletter, feel free to forward it to a friend, or two.

further reading

Mythologies, A Lover’s Discourse and The Death of the Author by Roland Barthes;

Family Lexicon, The Little Virtues and Voices in the Evening by Natalia Ginzburg;

Cesare Pavese’s diaries and The Beautiful Summer for a solstice read;

The Plague by Albert Camus

looking ahead

On Monday, I will be sharing some summer solstice picnic goodies for the annotated recipe series, which goes to paid subscribers. I’m also reducing the yearly subscription cost to The Onion Papers to £30 for the summer season. By subscribing, you’ll get access to the full archive and Monday entries and later ones. As ever, no pressure and thank you for reading my newsletter.

(If you’d like a paid subscription but now isn’t the right time, just drop me a line by replying to this email and I’ll comp one for you. No questions asked; I only need your email address.)

#22: pistachio and orange polenta cake, rose whipped cream

When I step into the kitchen, we’re approaching 11am. I have three hours before our guests are due to arrive for a pasta-making session, which means I have three hours ahead of me and no meal to cook. We will do that together. I tuck coffee in the moka, put it on the hob and grab one of the notebooks I keep at the end of the counter, where I scribble r…