Few vegetables have as much heart as the artichoke. An edible flower in the thistle family, the artichoke wears a green armour and greets those who venture near them with pointy arrows.

‘Try to eat me, and I will have you choke,’ the artichoke warns the cook.

But the cook isn’t defenceless. As you read this, one of the most widespread organ systems in your body is working miracles silently. It is called the immune system, it is mindless and follows a strange set of rules that, broadly, distinguish the other – as organisms that don't belong within the body – from the self. While I am not an immunologist, I am a home cook, sometimes sicker than other times, and I have learnt that a meal is, broadly, an amalgam of kitchen elements, such as salt, fat, acid and heat1, and a blend of subjective experiences and intuitions.

Leek instead of an onion; one teaspoon of smoked paprika and one teaspoon of sweet paprika; colatura di alici instead of balsamic vinegar for the vinaigrette; rub the artichoke’s hearts in corn flour before frying them in a pan. It is to kitchens that I owe a proactive mindset: less fear, more informed decisions, however small each one of them may be. The cook is adaptable.

There are various ways to clean an artichoke as each depends on what pairing you are after. In any case, the cook must remember that, if the body of an artichoke looks robust at first glance, its nature is prone to rapid oxidation – as soon as the outer shell is removed, the artichoke becomes exposed to the toxicity of the air and bruises. There is an easy remedy to this, which is citrus: fill a large bowl with cold water and squeeze a couple of lemons inside it. Keep a few slices for extra rubbing; healing is neither a homogeneous nor linear process.

The other precaution the cook must be aware of is that, once the artichoke is disarmed, it releases a bitter fluid. This is a protective response to the cook’s intrusion, nothing personal, as safeguarding is a response mechanism that can be expected of most organisms in both wild and domestic settings.

If the cook’s approach to preparing an artichoke can be methodical, being a healthy cook is an abstract concept. Health is embedded with luck and untransparent factors such as genes’ inheritance and context, partly, and privileges, like access to serious and unconditional care, mostly. Reciprocally, if we are taught that being un-healthy is a synonym for absence, the mind can easily be tricked to believe that regaining health is a commodity. Open your browser, scroll down social media, sit on the bus and head to the supermarket, and I can guarantee that you will be sold an array of products that promise a lifestyle above feeling fine and beyond health: wellness.

The principled cook would tell you that they could use a sharper knife for this, a fileted knife for these, or that, in a better world, they would have picked organic ingredients, that, with more time, they would have soaked dried beans overnight instead of using canned borlotti, yet nothing can take their process away from them. The said process – the staple of the cook’s cooking – is why you have come to eat at their table too – to be shown the lights you couldn’t see at first sight. The part of the self that interacts with others: empathy.

Steaming an artichoke requires less effort than it is rumoured, but it does ask for gentleness. Using a serrated knife, cut off the top of the artichoke (about one third) and rub its open end with some lemon. Cut the tip of the outer leaves with a scissor, then cut off the dry end.

To cook the artichoke, prepare a large pot with some water inside it. Squeeze some lemon juice and place a steel colander on top. Tuck the artichoke inside it, bring to the boil, then reduce the heat to a simmer, and let it be. You will know the artichoke is ready if you can peel the outer leaves by hand easily.

Nibble, dipping one leaf after the other into a vinaigrette (2 tablespoons of olive oil for 1 tablespoon of balsamic vinegar; 1 teaspoon of Dijon mustard and a pinch of rock sea salt), until you get to the heart of it, at which point, you simply have to bite into it with confidence.

Not all artichokes are the same either. Globe artichokes, which have bright and green outer leaves, are best steamed so you can preserve their buttery taste. If you are in the mood for something fleshier in June, you could follow the same steps with a Camus de Bretagne, a curvier sibling to the Globe that is cultivated in France. Purple suits the artichoke well too, so don’t forget the Italian Romanesco for your date; sweeter, it will do well in pinzimonio, so dipped in olive oil, with a pinch of salt and black pepper, or lightly fried, in a pan and over a medium heat.

But it is well known, if you are French, that the artichoke is a hopeless romantic indeed as, its coeur d’artichaut2, melts behind its thorny skin. One leaf after the other, it reveals something about itself, subverting the expectations the cook had carried on to them. To pick an artichoke well ripe is a difficult task as well. The cook is advised to hunt for compact, tight leaves with no pigmentations, for a vegetable that feels heavier than it looks, and, a cook who has looked at enough artichokes, will confess that there isn't such a thing as an immaculate artichoke.

If you are a fussy lover, you can still choose to clean the artichoke down to the heart, picking one leaf at the time, undoing its body. Start with pulling off the artichoke’s leaves with your hands as a knife could break its flowery heart easily. Keep trimming until you notice the leaves become yellowish and thinner. With the help of a serrated knife, cut off the stem, right where it is attached to the leaves. Trim away the outer, harder bit until you will find the tender white core within; preserve in lemon water. Then cut the tip of the leaves, just above the heart, which should be noticeable by touch. Now that you have a way into its heart, with the help of a teaspoon, scoop out the furry beard that covers it. Transfer the clean artichoke in the lemon water to prevent it from oxidising.

It isn’t the illness that is invisible but the other who refuses to see the illness within.

Once you’ve cleaned the artichokes, a risotto isn’t inconsiderable. Gather some chopped parsley, garlic and a small chilli; lightly fry in a large casserole. In the meantime, prepare a broth by bringing water to the boil inside a pot, with the discarded artichoke leaves. Return to the pan, add the trimmed artichokes and swirl around with a wooden spoon. Cook until tender, though they should preserve a bite. Add the rice, give it a stir, and pour enough stock to cover the rice. Reduce the heat; simmer. Add more stock if the rice dries out faster than it needs to cook. Once you’re a few minutes away from your preferred risotto rice texture, add the (peeled) prawns, cook until their flesh turns bright pink. Mix well, turn the heat off, cover the casserole with a lid and let the risotto set for a few minutes.

Serve,

so we could taste the artichokes risotto together. Even if we did, I still couldn’t control what you will make of the dish, forasmuch as we can’t control what the immune system will do when that other encounters the self. And, perhaps, just imagine for a second, you sweet coeur d’artichaut, if we lived in a world where other could also be self. Where the self could be undone so the other could fluidify the self, and vice versa. A world where trimming didn’t mean shrinking but being sharper, more individual amongst a community of individuals. A community in which other beholds selves and selves care for others.

Imagine, transformative justice lifting like droplets of steamed water, towards a community of care, therefore collective healing. It may sound far away from our realities, but it isn’t unreachable as the cook can still acquire plenty of other skills than those of the kitchen. Reading Audre Lorde’s The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action, I began learning a great deal about bravery and that, if language is the transformation of silence into an act of self-revelation, and thus it seems to be fraught with danger, it is necessary.

‘In the cause of silence, each of us draws the face of her own fear – fear of contempt, of censure, or some judgement, or recognition, of challenge, of annihilation. But most of all, I think, we fear the visibility without which we cannot truly live.’ — Audre Lorde3

It is a powerful sentence. But, if I am being honest, I am quoting Lorde for the distraction here. If I have written in praise of eating in bed before, or about baking against ableism, these are not words I produce without a cost. The value isn’t the same as the one used to quantify those publicised wellness routines and pills, but it bruises, still. I call it shame –

asking questions and requiring more tests; cancelling plans; being grumpy; keeping my socks on when I am otherwise naked on the examination table; not wanting to tick the gender box in the yet another form; not knowing if my relatives had any of the conditions listed; not knowing; knowing too much; being stubborn as hell, and refusing to call this life hell; finding beauty in the wounds; being, not being enough, being too much; loving in red

I deleted the above paragraph many times, until I opened the kitchen cupboards with hunger and found a jar of preserved and prepared artichokes. If the switch happens within, it doesn’t happen because of the self. To be sick, either for a spell or chronically, is neither a choice nor a fault; mutually, to heal is neither a matter of willingness nor a set of good behaviour.

Another truth about the immune system is that sometimes the error happens within the self, as it is the case with autoimmune conditions, when immune cells don’t differentiate other from self and, as they keep thinking that they are at threat, they respond with defending themselves which, in this instance, means that they attack their own kinds. Other isn’t always foreign. Self isn’t always the opposite of other. Other(s) can be self. The set of autoimmune conditions is diverse, so are bodies, and so is their gravity and the impact they have on an individual’s life.

The cook would add that to test an abstract recipe, one must cook from it. In a bowl, toss together some haricot beans, chopped celery, the said prepared artichokes and capers. Drizzle some olive oil, sprinkle some salt, black pepper and nigella seeds on top. Eat the salad as per your appetite’s requirements. Sometimes resilience is knowing how to spend the energy, and, in my experience, if not the cook, an artichoke will send a warning when trimming must end, as I suckle each end of its leaves, nibbling on the meat, until I reach the fur that protects its heart, when I must keep going but carefully, because care within today’s ableist societies is an act of resilience. To keep caring despite and even if, for as long as there is care to give, which is for as long as there is life to find ripened.

As I said, I am not a doctor, just a queer home cook who has trimmed enough artichokes to tell you that this one is for the messy, voracious lovers. It will leave more waste than it will feed you but, coeur d’artichaut darlings, what a bewildering thing life is.

margaux

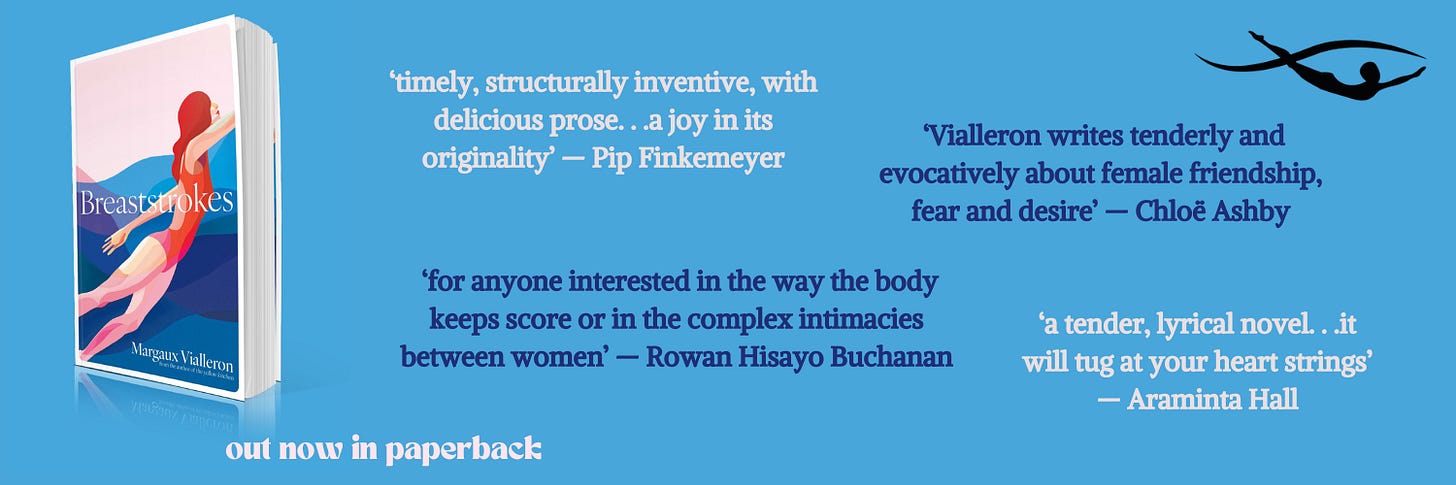

PS. if you enjoy my work, the best way to support it is to buy a copy of my novel, Breaststrokes, which has just published in paperback. It is currently discounted on Bookshop.Org (at £9.49 ) and, in one click, you could brighten my day as well as the one of indie bookshops. merci <3

*available in all, good bookshops such as Bookshop.Org, The Portobello Bookshop and Waterstones.

Thank you for reading The Onion Papers. i’m margaux, a writer and cook, and this is my hybrid newsletter. you can subscribe and come back for seconds (Thursdays are for long reads and Mondays for annotated recipes, both come out every other weeks).

This is a reference to Samin Nosrat’s brilliant cookbook: Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat: Mastering the Elements of Good Cooking (2017).

Literally means ‘artichoke’s heart’ in French and is a common expression to speak about someone who falls in love easily and/or often.

First published in Sinister Wisdom 6 (1978) and The Cancer Journals (Spinsters, Ink, San Francisco, 1980). It is now available in Sister, Outsider (2019).

Such a tender and beautiful read, thank you for sharing this with all of us <3

This was a lovely, tremendous read, Margaux!