‘Very early in my life, it was too late.’ Marguerite Duras wrote on the first page of The Lover. This month being January, I’ve read many social media posts, articles and newsletters about setting or not setting goals and intentions for the year ahead, in/out lists, etc. I turned thirty years old at the end of December. Oh, I confess, I’ve been thinking about time at all times of the day and the night —

I wake up to find the moon has carved a pocket of light for herself. Beautiful crescent. The lights at the Tesco Express around the corner switch on. I can see it from my bed, through the window, and for a minute I can’t remember if the lights ever switch off. 6am: it’s officially opened, not just lightened. I get up and I head to the bathroom. A spot on my left cheek, red, I hold a grudge; my hands so dry,

‘It was already too late when I was eighteen. Between eighteen and twenty-five my face took off in a new direction. I grew old at eighteen. I don't know if it's the same for everyone, I've never asked. But I believe I've heard of the way time can suddenly accelerate on people when they're going through even the most youthful and highly esteemed stages of life. My ageing was very sudden. I saw it spread over my features one by one, changing the relationship between them, making the eyes larger, the expression sadder, the mouth more final, leaving great creases in the forehead. But instead of being dismayed I watched this process with the same sort of interest I might have taken in the reading of a book.’ – Duras’ quote continues.

Until I picked my copy of The Lover again last week, I had forgotten about the second part of the quote, yet as I re-read it now, I realise that it matters for the sake of contextualisation. ‘I saw it spread over my features one by one, changing the relationship between them, making the eyes larger. . .’ adds the tender touch of one’s personality to a sentence I had judged harshly in isolation. Regret and the fear of growing old came to my mind as I had granted the sentence meaning through a duality – ‘very early’ vs ‘too late’ – as if the consequences of the past and the anticipation of the future should strikethrough the present. Except that Duras goes beyond this, the paragraph develops and she merges past-present-future into one amalgam that is the body; the living body as part of time passing rather than it being subjected to its movements.

Marguerite Duras was a novelist, playwright and filmmaker. As I wrote in Monday’s newsletter, Stay at Home Moon: on January, Marguerite Duras’ kitchen and a lentil soup: Her writing twined the personal and the political. She said that the story of her life didn’t exist. But the novel of her life did. She wrote against genres and classification, and she celebrated literature as her kind of truth. Duras was honest and vulnerable, truthful with her words and her practice – and she was renowned to be a good cook and convivial host.

Going back to The Lover as a novel. It was published in 1984 in French, won the prestigious Prix Goncourt the same year, was translated widely and was received as an ‘autobiographical novel’. Based in Saigon in the 1930s, the book is the story of a clandestine romance between a young woman from a poor, French family and an older, wealthy Chinese man. There is an undeniable international and timeless appeal attached to that short blurb – to love despite – but I also think that the success of The Lover is down to the narrative structure of the novel itself. Through agglomerations of details, repetitions and reported sentences – ‘I notice that I desire him.’ – Duras tells us as she feels, not as she lives. Whereas linearity is lost, the moods of a life being lived is captured: Duras writes her body;

the body as a witness.

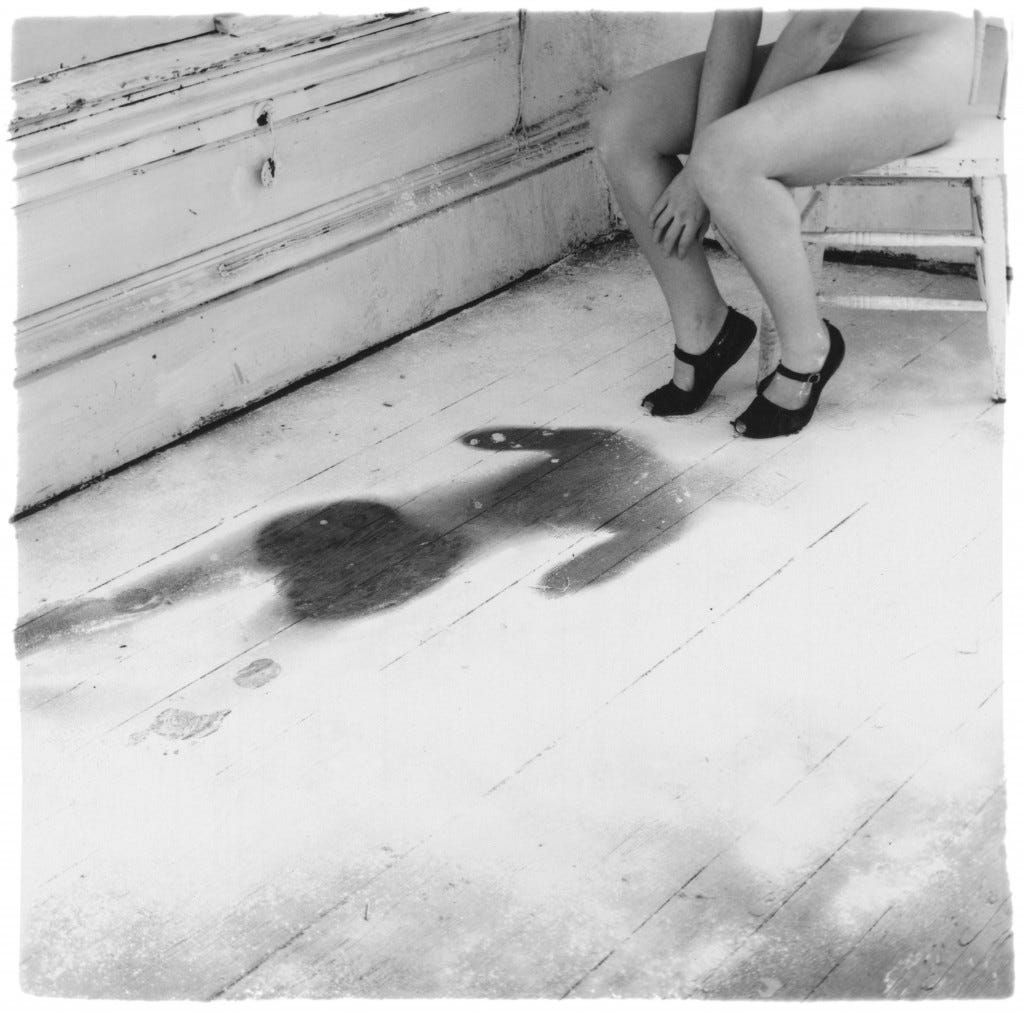

This night is moonless. I remember Frida Kahlo, who had a special easel fitted above her bed so she could paint lying down in bed. And Francesca Woodman who jumped to her death at the age of 22 years old. I see one of her blurry self-portrait photographs, a distorted body, either physically or through mirror games, sometimes naked or hidden in a blur. I love her very much, irrelevantly.

While they use different mediums (writing vs photography), there are similarities between Duras and Woodman’s methods, immediate and sharp. They constitute their own subjects, yet they speak to me; to us, readers and watchers. So I read Duras’ extract again and I think about the body as a personal space where we dispute memories with our own selves. For capitalist structures to thrive, individual’s natural cycles must be forced into unnatural rhythms, insofar that Earth, as the mother of all bodies, is collapsing too, pushed into unnatural edges as her wilderness is restricted. Either weather patterns or bodies, organic energies clog to extinction – until we rewrite them ourselves to voice our conditions. That is, bodyclocks as a resource for socio-ecological history. Bodyclocks for art-making, for writing.

Afternoon. Waiting for my coffee to brew; snow has become floods. Virginia Woolf ‘sunk deep among pillows.’ Crows caw loudly outside of the window. I could have baked Maya Angelou’s caramel cake, if only I had taken the time.

To write the body rather than to write about the body matters to me. My experience in looking for ways to articulate invisible illness outwardly has taught me that writing the body is how I find a truth that I trust. An experienced truth instead of an assumed reality, such as the syntax of breathing and the vocabulary of a pain as it snaps. The non-writing of a brain fog. I believe that there is activism in telling our bodies – sick, queer, estranged, healthy, fatigued bodies as they are – unfiltered languages to paint the symptoms of the world that scars them. I taste blood in my mouth, chewing my cheeks as I type this.

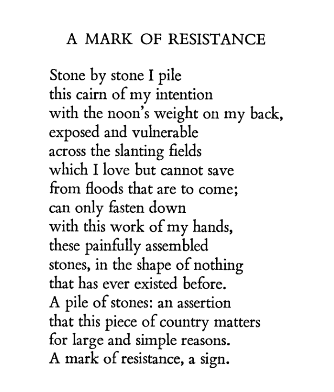

I’m reminded of a poem by Adrienne Rich:

I head to the library and I sit at a table on the second floor, next to the encyclopaedia and the dictionaries. I type for a while, I stare for another, I look up the word ‘Tender’ for a sweet, few minutes of procrastination and I’m reminded that a tender boat is ‘a small boat that brings fuel and supplies to larger boats in ports.’ And I think about sending this newsletter as a tender boat towards you; words, including the absence of words, as tender boats between our bodies. I want to hear you cluck your tongue, the lisp of your worries and your laughing happiness, and not to summon my language over you, yet I promise myself to speak a language of my own – and so we tend to each other. Perhaps we’re free like water and we pick a light pink pebble to bring home with us; so we can each carry on, and we remember to look around us before looking back.

‘When the past is recaptured by the imagination, breath is put back into life.’

— Marguerite Duras

You can call me out for being a dreamer. I hold my hands up, and I say: ‘It’s January after all.’ And j’écris,

I punctuate, each grain de beauté after its red spot;

summertime worries and winter spells.

A slip of the tongue,

mon corps and its language; a body’s syntax.

Margaux

Embedded with the above is the immense privilege of being in the position to speak up and the chance of being heard. Every day I wake up horrified that we haven’t reached a cease-fire in Gaza. Let 2024 be the year we don’t associate governments with the civilians oppressed under the said governments. If you can consider a donation, here is a link to MAP (Medical Help for Palestinians). And you can write to your MP – and keep writing to them. (the latter link is for UK residents).

Further reading:

On Maya Angelou; Marguerite Duras; Frida Kahlo; Adrienne Rich; Francesca Woodman. In Praise of Eating in Bed, an old edition of The Onion Papers, also on Virginia Woolf and illness.

Art Monsters by Lauren Elkin and The Story of Art Without Men by Katy Hessel

Something to eat? I shared a delicious, hearty lentil soup on Monday (for paid subscribers), or you can head to TOP Pantry.

I’ve also started a new list for new (to me) cookbooks on TOP’s affiliated Bookshop.org. Please note that when you purchase a book from my affiliated shop I receive a small share, however this doesn’t impact the author’s income.

I have a new website, and this year I’ve more availability for mentorships and French classes.

Thanks for reading. The Onion Papers is a reader-supported publication. If you enjoy my work, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription and you’ll get access to the full archive and weekly entries. It costs £4 per month and you can unsubscribe at any time. No pressure: I’m happy you’re here either way.

I felt this so much. It’s interesting to see how our woman experience seems to have a connecting thread, even though we come from different places. Thanks for sharing your thoughts. I wrote a reflection of my own about the time I turned 30. You can read it here: https://open.substack.com/pub/truthndare/p/growing-up-growing-old-and-growing?r=w90wb&utm_medium=ios&utm_campaign=post

I loved this one so much ❤️