On a random day, I visited the Gallery of Modern Art in Glasgow. I was zigzagging between the exhibited objects aimlessly but curiously, an approach one can adopt when art is free to access, walking between white panels with silent movies projected on them. Whereas, on the external walls, unrelated paintings were captioned with titles, artist’s names and materials.

‘Is this art, or can I sit?’ A man asked one of the museum staff. His voice resonated inside the quiet hall – the echo rendered his question urgent as his tone deepened and intensified his presence. After a brief exchange with the attendant, which I couldn’t hear, I looked at the man as he sat on the white garden chair, his legs collapsing underneath the seat and his shoulders folding forward, a pearl seeking shelter inside an oyster shell. He vacated the museum before I did, leaving only empty chairs behind him.

The sudden stillness awakened a feeling inside me. An energy; a desire? I wanted to sit on that chair too – would it make me artful? Yet, something else prevented me from taking actions. An authority. The sight of an empty chair comes loaded with hints – an absence must have reasons the mind can’t ignore – until I began a quest with empty chairs and their representations in the arts, after which I discovered that an empty chair can become a transitive verb too. To take part in an empty-chair protest is to draw attention to our refusal to participate in a debate or an event. It is an intended absence, meant to be noticed.

On 24 June 1880, the Dutch painter Vincent van Gogh wrote a letter to his brother, Theo. At the time, Vincent van Gogh had returned to live at his parents’ house after failing his university exam in theology and being let-go from his placement as a Sunday-school teacher. (The board members had declared that he was too fragile for the role; that is, too sensitive when he was exposed to poverty, lacking speech and organisational skills). In the meantime, Theo had moved to Paris for work to assume the traditional role of ‘the son’ on behalf of his older brother and to support the family financially. In the summer of 1880, he visited home to address his brother’s future. The two siblings walked and talked for days and, just before Theo headed back to France, the Van Gogh brothers had an argument about life trajectories, family duties and money, and the altercation troubled Vincent van Gogh greatly. He then followed up with the first letter in a lifelong correspondence. Theo, who had encouraged Vincent to focus on drawing and to pursue a career in the arts, for which he had identified his brother's talent, will go on to support him financially and materially and, to some extent, encourage him mentally. Reciprocally, Vincent van Gogh would rely on his brother throughout his entire life. In Vincent van Gogh’s style, both self-afflicting and self-confident, he wrote:

‘So instead of giving way to despair, I took the way of active melancholy as long as I had strength for activity, or in other words, I preferred the melancholy that hopes and aspires and searches to the one that despairs, mournful and stagnant.’

Van Gogh continues the letter with his temperamental writing style and fleshy vocabulary by debating some of his choices, in regard to his unkempt appearance and financial situation, as well as the scattered state of his studies, all the way to returning to the source of the argument between the two brothers – how they had grown apart over the years – to which Van Gogh earnestly responded, in writing:

‘But in fact there were a change; it’s that now I think and I believe and I love more seriously what then, too, I already thought, I believed and I loved.’

It was then that Van Gogh committed to studying perspectives, colours and materials, which he had identified as the first, technical step to become an artist –

‘in my unbelief I’m a believer, in a way, and though having changed I am the same, and my torment is none other than this, what could I be good for, couldn’t I serve and be useful in some way, how could I come to know more thoroughly, and go more deeply into this subject or that?’

forward—

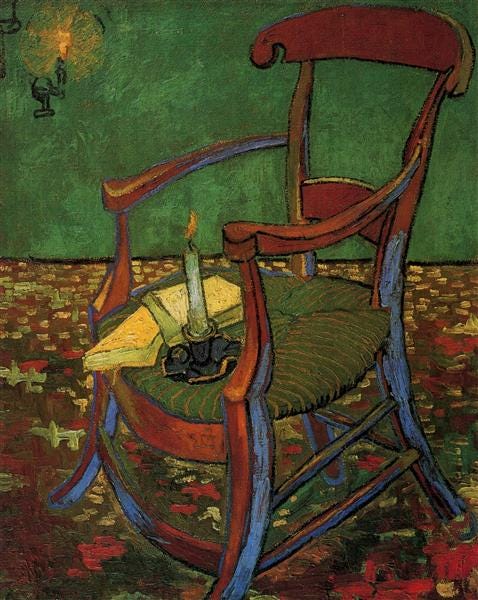

In December 1888, Vincent van Gogh painted a set of two canvases, each featuring a chair as the main object-subject. Van Gogh’s Chair (1888) became one of the most recognisable paintings in the world. The oil canvas depicts a rustic woven straw seat, brushed with the colour palette of wheat fields that characterises Van Gogh’s brush, as well as a tobacco pipe and pouch on it. The second painting, Gauguin’s Chair (1888), uses mainly red and green hues and features an armchair, which looks expensive with ornaments as well as a couple of books stacked on it. The artwork is playful with light, the colour scheme darker, and a candle is lit at the top of the chair. The painting is a homage to Van Gogh’s friend and contemporary artist, the French painter and sculptor Paul Gauguin.

While the two paintings were produced the same year, Gauguin’s Chair only became known to the public years after Van Gogh’s Chair was first exhibited, and the timeline wasn’t coincidental. A Dutch researcher in Art History and conservator at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam uncovered letters implying that Theo’s widow, Johanna Bonger, who had become close to Vincent van Gogh too, had inherited the paintings and kept Gauguin’s Chair hidden because of her dislike for Gauguin1.

[Dislike may sound like an emotional wording here, but it is Vincent van Gogh we’re talking about and, with all my uncredited sensibility for the painter, I would argue that Bonger’s reasons were clear and quantifiable.]

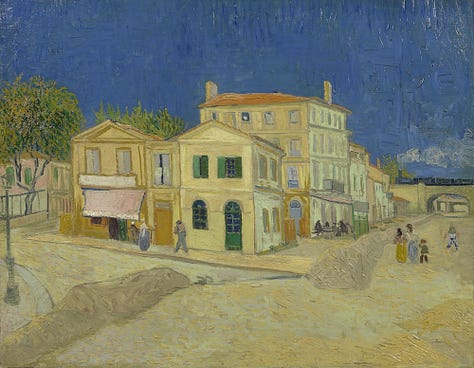

During the fall of 1888, for a period of sixty-three days, Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin lived together in a modest, yellow house located in the French town of Arles. Vincent van Gogh had arrived earlier than Gauguin and, in his letters to his brother and to Gauguin from that time, he spoke about furnishing a studio and bedroom to welcome his fellow post-impressionist painter with his renowned passion, so together they could work and study by the surrounding countryside. It was a good time in Van Gogh’s life, as he had had some paintings accepted by galleries, and he was gaining a form of public and critical recognition for his avant-gardist practice. With a certain enthusiasm, or even optimism, forasmuch as the letters’ elevated lexicon would suggest, he immortalised the house with a painting titled The Yellow House (1888), and he called the house the ‘studio of the south’. However, soon after Gauguin had joined Van Gogh, a virulent fight between the two artists took place and, sooner after that, Van Gogh suffered from a mental breakdown and cut his ear off. [I am aware that many mythologies around how and why Van Gogh cut his ear exist, but I am not interested to dwell on the gossip. It is my opinion that Van Gogh gave enough to the public; he had ills of his own, too, which shall remain private.] On 23 December 1888, Gauguin sent a telegram to Theo, who travelled from Paris overnight and, on Christmas day, both Theo and Paul Gauguin returned to Paris, leaving Vincent van Gogh behind. Gauguin and Van Gogh would never see one another again and Gauguin won’t only declare that Vincent van Gogh was mad publicly, but he claimed to have taught him how to paint. Van Gogh, on the other hand, continued to write him letters from the hospital:

‘In my mental or nervous fever of madness, I don’t know quite what to say or how to name it, my thoughts sailed over many seas. I even dreamed of the Dutch ghost ship and the Horla, and it seems that I sang then, I who can’t sing on other occasions, to be precise an old wet-nurse’s song while thinking of what the cradle-rocker sang as she rocked the sailors and whom I had sought in an arrangement of colours before falling ill. No knowing the music of Berlioz. A heartfelt handshake.

Ever yours,

Vincent’ (21 January 1889)

In my personal journey, I had come across Van Gogh’s empty chair paintings first. When I first laid my eyes on them, I hadn’t read the letters between Van Gogh and Gauguin, pre and post the accident, and I hadn’t heard of Bonger’s interference or, as I came to interpret it, her empty-chair protest by hiding Gauguin’s Chair. Still, the paintings had a profound effect on me and became two symbols for loss. As good art does, they invited me to wonder, asking what/who could be sitting there – the two chairs working as phantasms, the receptacles for a presence that couldn’t be present anymore. Outside of time yet firm with past time. Then they acquired new meaning, something felt, wise or unwise but known from experience. As I read about Van Gogh, and as I kept reading from him in his own words, through letters from the year he spent in an asylum as well as the letters he stamped from his time in Auvers sur Oise, a few kilometres away from Paris, where he met friendships again, the empty chairs became a form of hope – growth, life expectancy stretching with small notices. They evoked feelings such as mourning and intimacy, but they were never emptied again. Everything about them was meta and active, bubbling in favour of my poetic affliction, or my addiction to finding meaning in nature, so it can serve my purpose of showing what I want to say. I needed to keep looking at them. And I did, and the portrayal of those two chairs became the proof that the paintings held far more in them than I had first imagined – that, with a touch of ‘active melancholy’, hoping and aspiring and searching with them, I had unlocked a new path that led me beyond the first layer of appearance. The two chairs became mirrors, somewhat telling me about Gauguin and Van Gogh, about the yellow house and (post-)impressionist movement(s), and somehow about me, my fears and solitudes and dreams. Gauguin’s Chair wasn’t a ‘well illustrated chair with a candle on it’, nor the other part of Van Gogh’s 1888 chair diptych, with it being the less, for no better word, good one. No, it was Van Gogh commemorating what had happened between him and Gauguin; it was a work of remembrance, of trauma at most, or a scar at the least.

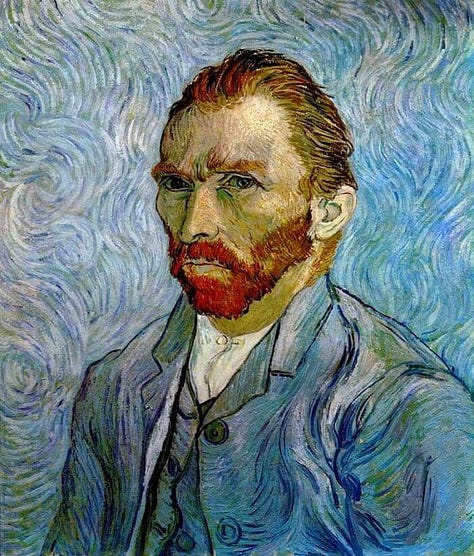

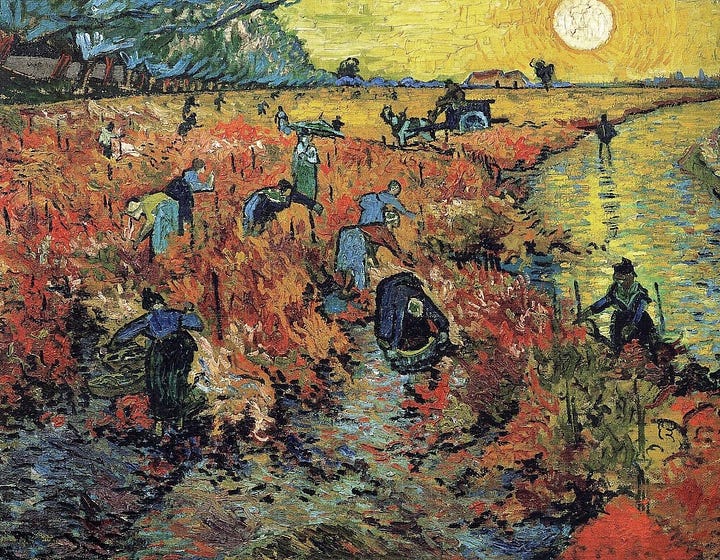

Van Gogh was known to be a person of intense passions and who thought to be always right. He upset many people and struggled with his mental health throughout his life. He also painted some of my favourite paintings, such as The Potato Eaters (1885), Red Vineyards at Arles (1888) and Wheatfield with Crows (1890), to name a few. Since my first visit to the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, at the age of eighteen years old, I have felt close to the painter in spirit, and I cherish the collection of his letters2 for the vexations of human life they disclose, without censorship or shame. In painting and in writing, I am drawn to Van Gogh’s loyalty to his own vulnerabilities. His words read like his paintings, filled with hidden subjects, and the more I read them, the more I realise that I am most grateful for his teaching about focus as an uncalibrated process. Van Gogh wasn’t afraid of digressing or meandering, for as long as he followed his intuitions, going deeper into the topics that picked his interest, confronting the people he loved, enough to love them more thoroughly, never letting go, digging and digging and digging, an eagle-eye hunter for the shades of life that coloured the cheeks and landscapes that surrounded him. He led an existence against appearances, through a series of life-long, empty-chair protests.

Perhaps the word dedication could be applied to summarise how Vincent van Gogh approached his art and made, in his own words, ‘things inconvenient for himself’, but I like to remember that he was also an observant who allowed for coincidences to chip in:

‘For the great doesn’t happen through impulse alone, and is a succession of little things that are brought together.’ (22 October 1882)

I often think back to the unknown man at the GoMA and the greater question he had asked, which remained unanswered: who decides when a chair becomes art or when a chair remains an everyday object? Or, in Van Gogh’s words:

‘why I’ve been without a position for years, it’s quite simply because I have different ideas from these gentlemen who give positions to individuals who think like them.’ (June 1880)

The thought-process had led to more questions too – could societal orders make a self-defining commodity such as a chair – ‘a separate seat for one person, typically with a back and four legs’ (Collins English Dictionary) – become performative too? I followed Van Gogh’s teaching on that one, hoping and aspiring with active melancholy, as I searched for other representations of chairs in the arts and through history, digging old postcards and internet archives, stepping inside museums to find all sort of chairs, from oil paintings to carved wood, with their shapes and shades switching alongside historical periods and artistic movements. As soon as I started looking, they were everywhere:

In 1870, the British painter and illustrator Sir Samuel Luke Fildes was forced to reconsider his work schedule. Charles Dickens had died suddenly, therefore there wouldn’t be a second half of The Mystery of Edwin Drood for him to illustrate. Still, Fildes headed to Dickens’ family house and, at their request, ‘in the house of mourning’ after the writer’s funeral, he sketched The Empty Chair. The watercolour drawing was described by the artist as ‘a very faithful record for his [Dickens] library.’

The chair had become an entity for the dead writer. This drawing, which feels void, without perspectives or originality, has stuck with me for its plain honesty. It doesn’t represent emptiness: it exposes an absence, the end of an act, the silence after the performers have retired backstage – silence. The Empty Chair doesn’t give away any details about how Dickens lived, but it shows his death.

Looking at Dickens’ empty chair through Van Gogh’s empty chairs, I was faced with its depth; beyond the writer’s death and other than the manufacture of a chair, there was context. And context is moveable, through mindful exercises and time passing. The chair’s seat and legs chiselled the bones for historical and societal complexities that gravitated around it. I recognise that I, too, am enthusiastic about a niche passion. Still, threading with that ‘active melancholy’, I was spoiled with life details to rejoice for – a treasure hunt with ghosts. Where I saw a chair, I found the ashes of a presence, either people who had once sat there or those who never got to sit there. I found a link between the body and the soul as both the chair and the body hold ideas – the chair for the seater; the body for the mind – and each enabled a certain physicality, in that they either barred or allowed a person to occupy a space, and to mark it.

In my search to get to know melancholy better, as a state of mind and body experience, I encountered another author of supersonic prose: Robert Burton, who penned The Anatomy of Melancholy. This is a thousand-plus-page encyclopaedic work, blending classical quotations, personal observations and notes, which the author expanded five times between the first publication in 1621 and his death in 1640.

Methinks I hear, methinks I see,

Sweet music, wondrous melody,

Towns, palaces, and cities fine;

Here now, then there; the world is mine,

Rare beauties, gallant ladies shine,

Whate'er is lovely or divine.

All other joys to this are folly,

None so sweet as melancholy.

— Robert Burton’s abstract of melancholy

When Burton was writing The Anatomy of Melancholy, books had become more available than ever via the invention of the printing press. There was an intellectual movement towards general knowledge, and the 17th Century relates to our contemporary days for its concerns about information overload and how erudition might influence our psychologies and behaviours, thus our minds and, consequently, how one interprets and performs the body. I encountered Burton again recently, as I read Caroline Crampton’s A Body Made of Glass (2024). In her history of hypochondria, Crampton draws a parallel between melancholy, its ‘infinite varieties’, as Burton put it, and hypochondria. Crampton reveals that, when Burton wrote Anatomy of Melancholy, it had become ‘achingly fashionable’ to be melancholic, a trait that only affected the creatives and the rich, or those who had the means to pursue the illness of ‘being alive’. Hypochondria, as we know it today and as Crampton argues, is a ‘descendent of melancholy’ for the fixation it puts on the self and its shifting symptoms.

This stayed with me as it speaks to the bad reputations both hypochondria and melancholy have earned in an ableist and profit-production-driven society – as self-inflicted conditions; as paralysis; as numb; as a little sorry and sad; as products of the imagination. Before I had access to Crampton’s research, I had read Burton as a poet of the melancholic state, in appreciation of his cavalier approach to metaphors and the trust he put in digressions to end with new visions, as a precursor of Vincent van Gogh’s active melancholy – a way of life, rooted in feeling and empathy, for its narrow-minded radicalism and its great generosity, for the lights it reflected and each sorrowful corner it foresaw. For its bare humanity.

Regardless of our views on where melancholy and hypochondria come from, or whether they are conditions, Burton and Van Gogh both tell us one thing: with our pains as much as with our joys, we have agency. Imagination is a trusted friend of the mind, a guide for the body. Your pains are valid; whether they are diagnosable via a medical or via a thought process, that is a different question.

On that note, thinking of anyone who has been gaslighted by medical institutions in the name of hypochondria and/or melancholy before, I return to Vincent van Gogh’s letters, which also hold prequels and post-scriptum notes, each hinting on his brewing afterthoughts and insecurities. Van Gogh was human and craved sympathy from others. On Friday 23 December 1881, coincidentally, or tragically, exactly seven years before the night when he cut his ear off in Arles, he introduced his letter to his brother by saying:

‘Sometimes, I fear, you throw a book away because it’s too realistic. Have compassion and patience with this letter, and read it through despite its severity.’

Van Gogh drew resilience in the soul and talked about love as a pathway to get to know something and/or someone more thoroughly, on the condition that love was pursued with ‘a high, serious intimate sympathy, with a will, with intelligence’. I keep that one close to my chest.

And, in wishful thinking for the future, I want to see more people being welcomed to fill more chairs with dignity, protesting and organising to build communities of care. To that respect, I turn to American painter Alice Neel, who became famous for her large and bold portraits that gave a voice to people who had been silenced by the canon, such as left-wing thinkers and political figures, Black and Puerto Rican children, pregnant women and sick bodies. Despite working at a time of severe censorship and repercussions, Alice Neel was an active member of the Communist party, and her brushstrokes and art spoke against prejudices. Neel called herself a ‘collector of souls’, and she painted some of the bravest chairs I know.

The first one is Marxist Girl (1972), featuring Irene Peslikis, who was a feminist artist, activist and organisers. The second one is a self-portrait, which Alice Neel finished painting when she was eighty years old, in 1980. It had taken her five years to complete – ‘it was so dammed hard,’ she said. The painting shows Alice Neel naked, sitting on her ‘favourite’ stripey blue chair, with red cheeks and holding a brush. Her hair is white, her breast hanging like pears on a tree, her toes flirting with the ground, tiptoeing and confident; it is both a tender and revolutionary image, the figure of a mature woman and a response to the history of nudes that had long objectified women as erotic objects. It is, to me, the portrait of active melancholy.

Although it started on an arbitrary day, it took me years of searching and hoping to unsee the chair at the GoMA from what I had expected it to be and to aspire to see it for what it was – still is, to some extent. That is, a response to how I thought others wanted me to see and to experience The Chair, rather than for it to become a series of individual chairs that bear witness to our humanities or, to paraphrase Alice Neel, a collective of souls.

such a melancholic, am i!

margaux

thank you for reading. i’m margaux, a writer and cook, and this is my hybrid newsletter. If you enjoy The Onion Papers, you can subscribe and come back for seconds (thursdays are for long reads and mondays for annotated recipes, both come out every other weeks) <3

‘An answer comes in an article by Louis van Tilborgh, a senior researcher at the Van Gogh Museum, in the latest issue of Simiolus, the quarterly journal of Dutch art history.’, as highlighted in the Art Newspaper.

Vincent van Gogh: A Life in Letters, edited by Nienke Bakker, Leo Jansen and Hans Luijten.