Three Tokens of Time

baccalà with chickpeas and tomatoes, cavolo nero on toast and some lentils for good luck

The first watch I remember wearing had the colour of an unripe Granny Smith apple, a birthday gift from my grandmother. I have felt an unprecedented pressure about writing this edition of The Onion Papers – the first one of the year! – a follow-up from a time of unavoidable self-reflection in a world in turmoil, collapsing and regenerating. The new year is a rentrée for the grown-ups, a moment compressed under the pressure to review the expense of time passing and under the aura of what the future could hold.

Two things I believe in: community-led actions and that time is malleable, and by the latter I mean that productivity isn’t the sole valid measurement to count seconds, minutes, hours, nor to fill diaries. With this week’s Onion Papers, I’m taking you on an expedition through three ‘time capsules’ I visited during my holiday last week. Buckle up – oui oui, I have packed some food too.

Baccalà at the Ospedale degli innocenti

On boxing day, I went to the museum degli innocenti to see a retrospective of Dutch graphic artist Maurits Cornelis Escher. I walked to the piazza SS Annunziata in Florence, where the beautiful Renaissance building is located, and there I lost a little piece of my heart.

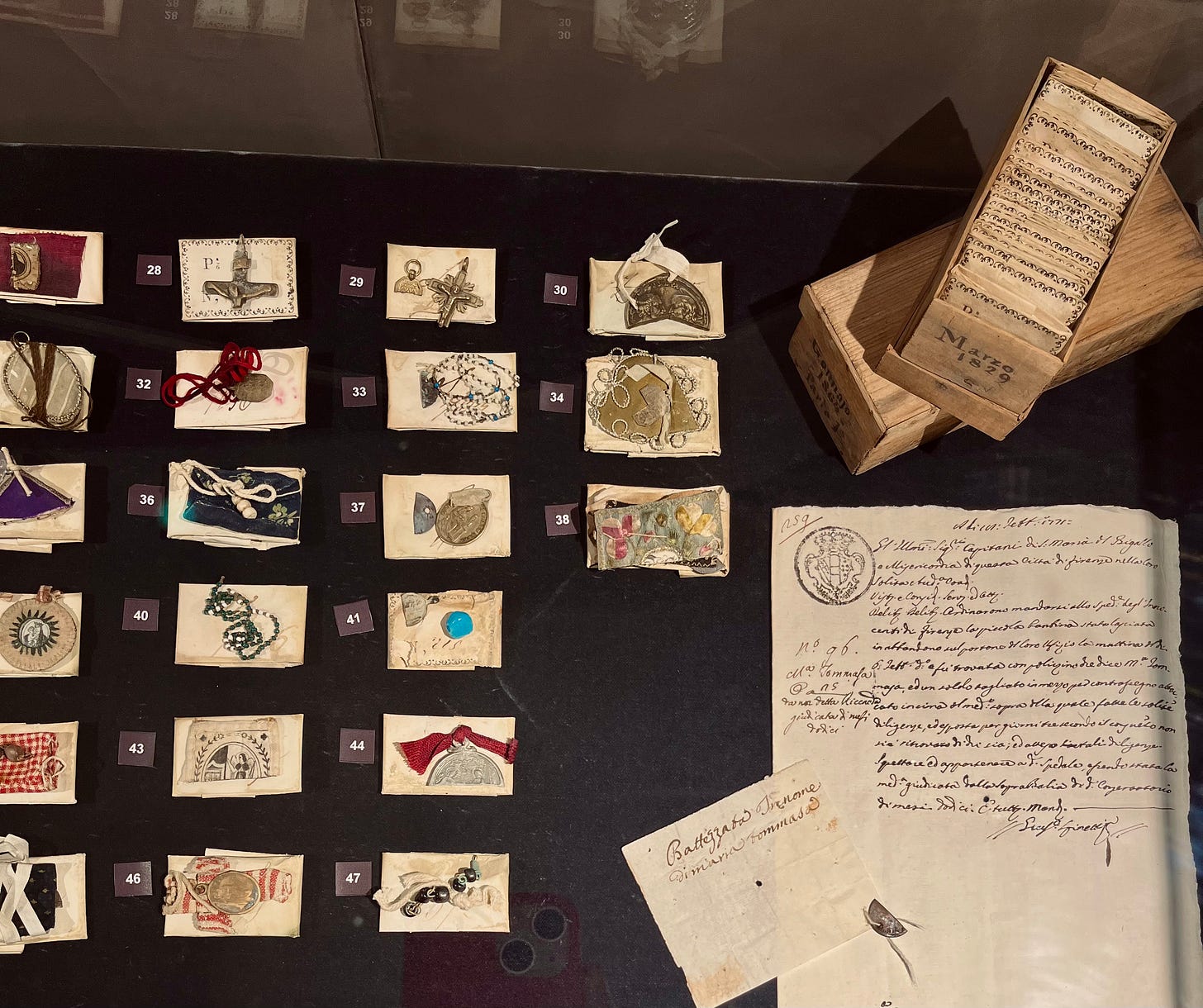

Commissioned by the Arte della Seta in 1419, the ospedale degli innocenti (the hospital of the innocents) is one of the oldest Italian public institutions, and the first one dedicated to the protection of children. An orphanage, its affiliated nurses welcomed a first child on 5th February 1445 – Agata Smeralda – who was dropped through the hospital’s dedicated grated window. While the system was designed to keep parents’ identity secret and to protect women who could be persecuted for having given birth out of marriage, the anonymous process made future identifications difficult. When you walk into the basement of the museum degli innocenti, there is a wall covered with tiny boxes that slide open and feature labels at the front – children names and dates of arrival are written on them. If you open one of the boxes, there you’ll find halved objects such as medals, pins, pieces of fabric, nothing of financial value, but the clue of a bond between a parent and a child. These are ‘brevi’ descending from the tradition of medicina popolare and find their origin in ancient Greece, when ‘symbolon’ (a physical object) was used as a material indication of an agreement or, in private practice, as a reminder of a family or friendship link.

The ‘brevi’ culture was important at the orphanage as Tuscan parents who required the assistance of the ospedale degli innocenti started to leave a broken object with their child (keeping the other half) – a means of future identification and, in most cases, remembrance. The objects were so deeply rooted into the workings of the orphanage that when the window was sealed and replaced with a delivery office on 30th June 1875, parents continued to bring tokens with them. It had become a requirement of the Italian law that parents register their child in person, administrative procedures and court ruling for children’s recognition were introduced too, yet administrators stapled the objects onto the child’s paper file. While the ospedale degli innocenti stands for the humanistic views of Florence during the Renaissance as much as the later legal response introduced safer systems for families’ welfare, the persistence of tokens all the way into the 20th century shows the strength of human connections before any forms of policing.

I’ll always regret not being able to meet Rosanna, my partner’s mother, or the feistiest of foragers I have ever heard of. Most of what I know about Rosanna, I have learnt it through Ludo’s cooking – nepitella, wild fennel, chimichurri – or through orders of baccalà con porri e patate at the restaurant. The dish melts in your mouth, creamy and sour, a bouncing act between the roots of potatoes and leeks and the saltiness of cod.

We cooked baccalà at home for the first time during the holidays. We made ours red and served it with chickpeas, our half of the token we share with Rosanna, and this one is for the families we hold in our thoughts – Baccalà with chickpeas and leek:

1 piece of baccalà: you should start desalting the dry cod three days before cooking it. Slice the fish in rough chunks and put them into a bowl of cold water. Leave aside but change the water once a day.

250g chickpeas, soaked in water overnight if used dry (canned beans work fine too)

1 celery

1 carrot

1 leek, sliced

1 bunch of parsley, thinly chopped

2 cans of tomato sauce

If you’re using dried chickpeas, bring water to the boil in a pot together with the celery and carrot. Pour in the chickpeas and cook them for 45 minutes.

In the meantime, in a large pan, fry up the leek and parsley with some olive oil. Cook until tender and add the tomato sauce. Swirl around, bring to the boil, then lower the heat and add the cooked chickpeas. Spread the fish chunks around the pan (you want them to be covered in tomato sauce) and slow cook for approx. two hours.

Once the dish is ready and you have had a first portion, my advice is to cover the pan with a lid, leave it aside overnight and eat the leftover the next day. The tomato sauce will have macerated into a thick, salty soap opera of a dish. It’s generous and tasty.

Cavolo nero con le frette, a postcard from Venice dated 31st December 1938

Last week, I spent three days in Venice. There are many things one could write about Venice, but the reason I’m bringing this trip up is because I collect old postcards and I had the most fun hunting for new treasures there. I spent hours looking and reading through boxes at Libreria Miracoli on Campo Santa Maria Nova and at the famous Libreria Acqua Alta – the postcards smell of damp, the paper is thick and dusty, the ink fades, but they’re hopeful testimonies for what words can do. I care little for the photograph or the picture because I’m nosy and I want to read what people had to say to each other. It’s an exercise in decoding handwriting curves and often in linguistic too – an archaeology of written language, or wonderful time capsules.

I bought three postcards during that trip: the first I’m still decoding; the second recorded cases of cholera, predicted poor business in Venice, and is dated 6th July 1911; the third one was written on New Year’s Eve.

Mon cher Edmond, it starts. The tone is polite and a little flirty – apparently Edmond had sent a ‘collective’ postcard (no details given about the nature of the group), before sending a second and separate kind letter to the author of the postcard. The sender goes on with wishing Edmond good health for the year of 1939 and asks for a response ‘without a delay’. Je t’embrasse, it ends, and I can’t stop wondering if Edmond ever wrote back, or if their future letters arrived safely as the events of World War II unravelled later in the year of 1939.

It’s impossible to go to Venice without eating your way through the city, handfuls of cicchetti. The word means ‘small quantities’ to name the snacks that were eaten to sponge glasses of ombre. The strategic location of Venice imposed it as a thriving merchant city, and it was tradition to cheer a new trade with a glass of wine – and to dust it with a gulp of food. You wouldn’t want to be drunk while doing business, would you?

Accept this Tuscan makeover of the cicchetti, Cavolo nero con le frette:

Cavolo nero, harder stems removed

Bread, sliced

1 garlic clove, peeled

olive oil

S&P

Bring a pot of water to the boil and cook the cavolo nero until tender. In the meantime, grill the bread and brush each side with the garlic clove.

Once the cavolo nero is cooked, dry it but keep the water as you’ll need it. Dip the bread (on both sides) inside the cooking water, spread the cavolo nero on top. Season to taste and drizzle some olive oil on top.

Stale bread works well for this, but any kind will do.

Cooking lentils while reading La Storia by Elsa Morante

The first book I read in 2023, is one I carried over into the new year: La Storia by Elsa Morante. A neighbourhood chronicle, La Storia focuses on the story of Ida Ramundo, a partly Jewish woman and single mother of Antonio and Giuseppe, and is set in Rome during and at the aftermath of World War II.

There is a complex approach to history and veracity in La Storia. Each one of the novel’s sections are prefaced with a chronological list of worldwide historical events, while the fictionalised sections follow a descriptive and abundant style (one that doesn’t shy away from the horrors of humankind), with interruptions from the narrator whose intention is to guarantee it happened this way. It’s unclear who the narrator is, and I adore that. Morante’s novel is a detailed archive – a novel of 655 pages in Italian – a demonstration that nothing happens in isolation and that individual’s stories thread the wider History.

It should be noted that the novel was first published in Italy in 1974, during the tumultuous 70s and at a time when a Marxist reading of history dominated the intellectual scene in the West. Despite her public recognition after winning the prestigious Strega literary prize with Arturo’s Island in 1957, and the obvious commercial success of La Storia (the book sold 800,000 copies in the first year), Morante was faced with a huge amount of criticism – her vision of history was too pessimistic, the collages between macro and micro historical events caused confusions, a maladroit work of poetry, it was an amalgam without a trajectory – and lifelong friends like Pasolini got lost into questioning her use of dialects. Morante was obsessed with accuracy! Authors such as Natalia Ginzburg, however, praised La Storia.

The question of veracity especially interests me here, along with Morante’s narrative tool: her decision to mirror fictionalised events and historical dates. Morante read Simone Weil, a philosopher of the margins and against categorisation, avidly; her reputation precedes her too, she wasn’t afraid of looking at humankind’s natures. With La Storia, Morante questions the role of fiction and the futility of romanticising historical events – it is a work of literature, as much as it is a warning. As I kept reading La Storia, it became apparent to me that this is the work of someone who reads history from the perspective of a minority, a retrospective that allows truth because it’s unreliable as much as a human mind that commits to surviving would be. Ida isn’t Jewish, but she is partly Jewish, a mother, but a single mother. I put La Storia away and it still haunts me because Morante retold history through paradoxes, an account that doesn’t accommodate a simple dichotomy between evil and good; this isn’t about which politics Morante believed in, but an ask to consider our lies when we search for the truth. With La Storia, I recognised Morante as one of the bravest authors I have ever read – one who dares to question the duality of hope.

It’s said that eating lentils on the thirty-first of December brings good fortune and health for the new year. The origin of the superstition comes from the shape of the lentils – look at them! – because they resemble coins. The traditional Italian recipe includes pork (cotechino), whereas in France there is a similar dish called Petit salé aux lentilles, served with carrots and onions. It requires slow cooking and while I was always a vegetarian, I would scoop the vegetables out of the casserole while it simmered on the hob when I was a child.

I like to cook lentils in a large pan because it gives them a mushy texture, and I find them nuttier this way. The method is similar as the one for a risotto – lentils for some good luck:

Lentils, soaked in cold water for 30 minutes and rinsed

Red onion, sliced

Parsley, thinly chopped

Cayenne pepper

Carrots, cubed

Celery, cubed

Mushrooms, sliced

Cans of tomatoes

A bouquet of sage, rosemary, bay leaves and nepitella (or any herbs)

Vegetarian broth

Start with bringing a veggie broth to the boil, then simmer.

In a large pan, make a soffritto with the onion, parsley and cayenne pepper. Once the vegetables are golden and soft, add the carrot and celery. Cook for 2 minutes and add the mushrooms. Cook for another 3 minutes.

Pour in the tomato sauce and attach the herbs bouquet onto the pan handle. If you have tomato purée in the cupboard, don’t be shy, and add the lentils next. Start pouring the broth in, a few ladles at the time, stirring often until the lentils are cooked. I like mine soupy, so I’m generous with both tomato sauce and broth, but it’s up to you to decide how you’ll consume your luck this year.

I’m aware that I have given you a partial read of any of these time capsules, an indulgence to my novelist imagination with a few good meals along the way, and I hope you have enjoyed the journey. These are intended as tokens from me to you for the new year because whatever your resolutions might be, if you have taken any, time flows and we can make amends.

May 2023 be full of small pleasures to build great joys, whatever your pace is.

Margaux