Beside my bed, a film photo hangs on the wall. The sky melts into the Mediterranean Sea, Bijou Plage, variations of pink in the backdrop of my tanned body. I must be ten or twelve years old with my bloated cheeks, messy hair and my front tooth missing. I loved summertime already: sticky fingers from the Nutella panini I ate for the goûter, salty hair; sweet and sour, there were no limits other than the buoys that marked the end of the lifeguard’s surveillance. Being out of breath was a sign for good times, running and swimming and blowing into inflatable boats, drifting and paddling with my brother, the horizon line in sight, a threat for our mother who watched us from the beach. I caught crabs between rocks, and I found my mother radiant. She often forgot to remind me and my brother to apply another layer of sunscreen and my shoulders are now covered with freckles, the embroidery of our family name – if only you could see my mother’s back. My brother was always more rigorous.

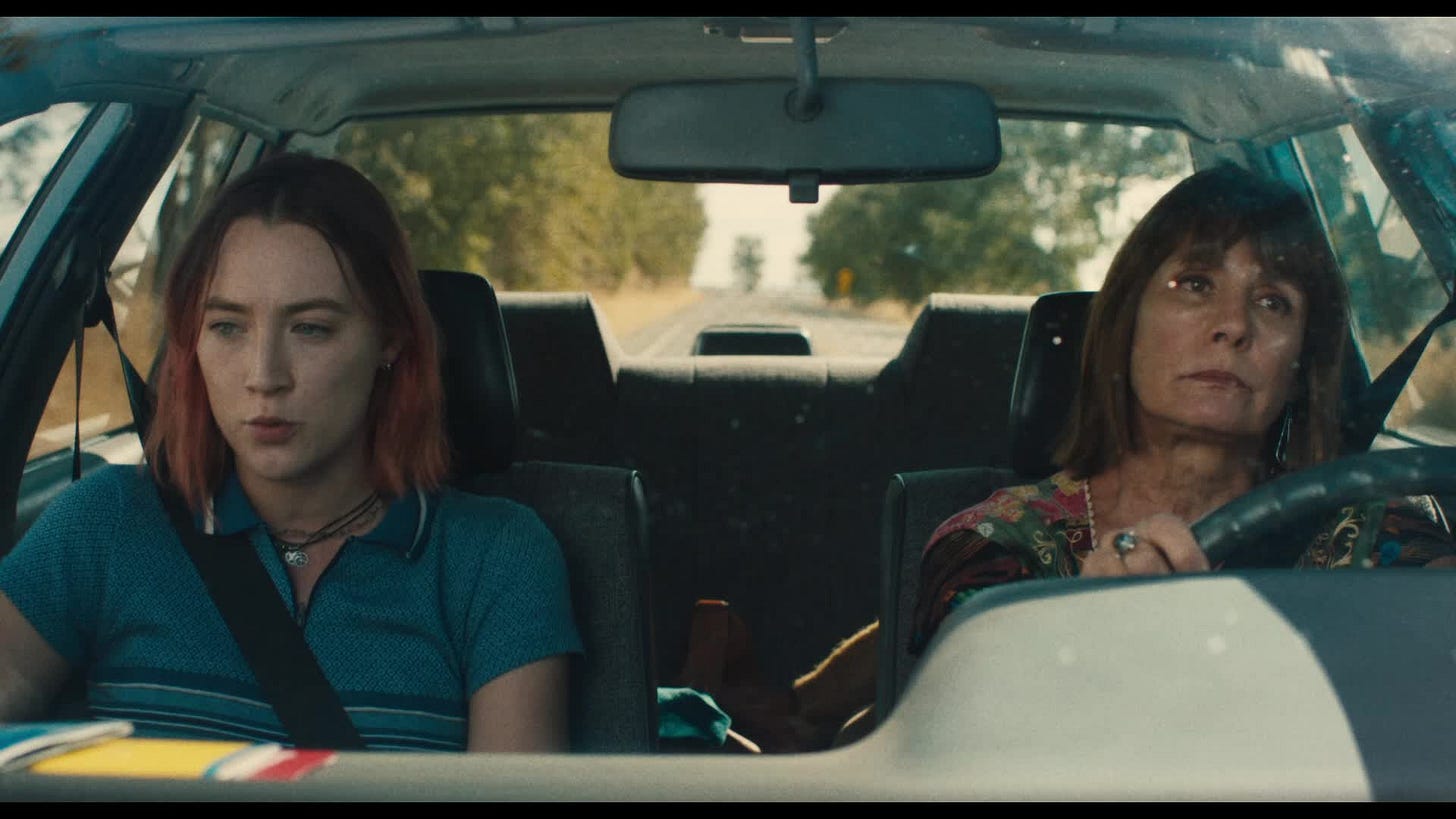

The three of us piled up inside mum’s Renault Laguna with our two dogs. Maman drove the 900-kilometre distance in one gulp while I sat next to her at the front of the car. I’m convinced that we spoke without a break for the length of the entire journey. My brother slept, while Chéri FM played in the background with interruptions for traffic updates, and he woke up when mum pulled up the handbrake. We did the reverse journey, on the thirty-first day of August, on repeat every year.

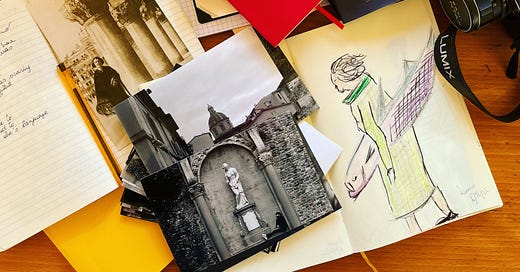

[2023: I’m walking on via Romana in Florence, the pavement narrows down and I must step down on the side of the road. I watch out for the cars all the way to Ponte Vecchio, then I’m hit with a wave of fearless tourists. I cross the Arno River and continue ahead until the leather market – at the corner, a photography shop. I drop films I shot between November and December 2022.]

I cherish this memory, but it asks how much I chose to forget about that present so I can cherish the memory. I can picture the car and the little pillow (beige with an otter sewed on it) I always took with me, but I can’t hear us.

‘You have no accent,’ my mother told me about two years ago (she never listens to me speak in English). She had come to pick me up at the airport and we were driving back to the house where she now lives. The car model is different and we talk little these days.

Her tone stayed with me, a hint of disappointment overshadowed by amusement; it’s foreign to move abroad to study literature and to write for my mother; she is looking for sa fille. Me before I, her daughter.

[2023: I drop the films and the man behind the counter tells me it’ll be two weeks before they’re ready because Friday is a bank holiday. I nod. It also takes longer to develop black and white films, he details as he pre-fills a form on my behalf. I didn’t remember loading a black and white film, but I don’t tell him this much. On the way home, I worry about the quality of the photos because I worked with colours in mind.]

Language conveys assignations, and its usage keeps one speaker to an allocated role within our social organisation. As one learns the grammar of their life, words paint our worlds with naming, calling, describing thus one builds an epistemology of one’s own. Mine wasn’t wordily but photographic. Ask me about an item I own, and I can tell you where I last saw it, or I’m likely to detail the fabric and motifs on my friend’s jumper at dinner last week. The film camera I gifted myself for my twenty-sixth birthday is my most cherished possession.

Moving homes has rhythmed my years since my parents’ divorce. I wasn’t eight yet and after doodling something on the wall of my first bedroom, it’s the family photos that I packed. I still do the same – anywhere I go, I carry a folder with film photos. Most of them are of poor quality, blurry and unimaginative, sticky with old tape and teared corners. Maman also holds some of our photo albums. They are stored somewhere safe that I know because she was told to get rid of them along the years – they use space, heavy and dusty with past times. She also owns colouring books. They pile up in the room where I sleep when I go back to France to visit her. Boxes of colouring pens sit on top of them too, unopened, and when I lie awake at night over there, I wonder what the names of all these colours could be. I don’t know, but I can describe them: the green of the ducks that live by the waterbeds along which we used to walk the dogs together; the green of the ski overall she owned when I was a child, the same shade as the Granny apples she buys for me when I stay at her house; the blue that waterfalls into grey, the colour of my mother’s eyes. These bleed into the landscape of our family.

I understand why my mother made a comment about my accent now. I needed to fall ill and to be scared, to have my heart broken and to love, to publish my first novel in English and to dare scribble a few words in French too, to flirt in Italian and to look at hundreds of film photos, old and new, to whisper through nights of insomnia; morning breaks, I visualise the journey. I stepped away from French as a mother tongue and it evolved into my mother’s tongue. Then—accent-less—I was speaking away from our future memories, so she said goodbye as she listened from the shore.

[2023: I collect the photos. I spread the photographs on the floor, and I spend some time looking at them in silence. I classify the photos by emotions instead of dates or locations. I’m bemused at the patterns that form before my eyes, and I disagree with the black and white definition. Shades of greys is what these films are – plays on light in a silent room.]

When I moved to the UK, my English was poor. I have found the experience of learning a language as an adult empowering because the linguistic process is reversed: I have a sense of who I am and I’m acquiring a new grammar to thread that identity within the spiderweb of social performance. It’s also a bewildering experience that makes me feel like an imposter with my emotions and in my body often.

One example: the first time I visited a surgery for my smear test in London. I sat and I talked of a ‘white loss’ to the nurse before me. She smiled politely when I said the words but interrupted me when I repeated them: discharge, she corrected. My mother had told me they were ‘pertes blanches’ when I hit puberty. I felt like a child in a woman’s body – I wanted to howl pertes blanches, pertes blanches, pertes blanches to the nurse. These were words that had been confined inside my intimacy until that day, when they turned visceral and I departed my teenager’s body. At that very moment, alone in a surgery in London and unconfident about my language, not only I missed the safety of knowing that Maman sat in the waiting room, but I also itched to share a pain—a fragment of myself—in my mother tongue.

The English language I speak and write is an on-going linguistic I’m building – a mothering tongue, the language of the moi. Mothering as the language to perform and unfold my intimacy as well as my identity. French is my motherly language – the lexicon in which I fall back when I hurt or must find recognition, a place where knowledge is one of the past, ingrained – whereas English is fluid, in-definition, a conduit for who I am (being) presently.

[2023: I post some of the film photos on Instagram. Mum comments with smiley faces who have hearts instead of eyes and guilt stabs me in the back. She had asked me to create a profile for her the last time I was in France (private, no photos) so she could follow mine. I should have sent photos to her directly – show her my life and explain why I love the shots in the kitchen as much, the baccalà we cooked in honour of my partner’s mother, and the balcony from which I captured Florence, my favourite spot in the city. I didn’t because I refused to translate these emotions back into French. I’d have had to think hard enough about the words behind the images, and this would have stolen the accommodating, intimate silence away from the pictures.]

‘There should be a non-writing, and it will come some day. A simple language without grammar. A form of writing consisting only of words. Words without grammar to sustain them, abandonment as soon as they have been written down.’

– Marguerite Duras, Writing, 1993

Mother marks daughter with the words she had murmured and talked to her – and trust me, I will never drink an infusion, only Maman’s tisanes can brew in my kitchen. This is my intimate dictionary and as much as I want you to read and hear me, I can’t help but to twist my tongue through the act of living.

‘C’est bien beau tout ça,’ I can hear my mum say. ‘But this doesn’t tell us what we’re eating for dinner.’ The answer is crab and asparagus lasagne (oat béchamel).

Making lasagne is a layering work, and this recipe is the product of Ludo and Valentina’s magic. There are no measurements because we talked and drunk wine as we cooked, please accept the loose grammar of our dinner:

You can either buy pasta sheets or make your own. If so, you’ll need:

Semola (or semolina if you can’t find the former)

Lukewarm water

On a wooden surface, make a volcano with the semola and pour in some water. Drop the water slowly as you go and knead until you have a homogeneous and consistent mixture. Once the dough holds together, flatten it with a rolling pin and cut it in long and rectangular pieces that fit your oven dish. Pass the dough through a pasta machine until you have reached the thickness desired.

The method for the filling is one that accommodates chatters, or the time saver edition:

Leeks, thinly sliced

Asparagus, roughly chopped

Crab (canned)

Oat cream

Flour 00

Nutmeg, grated

S&P to taste

Parmesan, grated

Preheat the oven to 180C fan. In a pot, fry the leeks and asparagus with some olive oil. Once the vegetables are cooked, pour in the oat cream. Maintain the heat on the low side so the cream doesn’t boil. Add the crab meat and start stirring, then add some flour, slowly and stirring, until the cream has thickened into a firm béchamel. This is a gentle process, stir and sprinkle more flour, continue. Grate some nutmeg, add salt and pepper to taste.

Time to assemble the lasagne. In an oven dish, spread a little bit of the béchamel at the bottom (instead of butter/oil). Fit in the first layer of pasta sheet, spread béchamel on top and grate some parmesan, repeat until you have as many layers as you like (or have preparations for).

We like ours crispy, so we polished it with a final layer of pasta sheet and parmesan on top. I highly recommend.

Crispy lasagne, a crunch, words; your words, my words; a simple language but our grammars.

Margaux