Market Days

a trip to Billingsgate and other local markets; a dinner party, some recipes, and thoughts

In this memory, I’m fifteen years old, and market day falls on Sunday. Merchants set white tents in the parking lot outside of the Avenue Jeanne d’Arc in the north skirt of Paris, but green grocers, the fishmonger and the butcher have permanent stalls inside the halls. I’m a teenager and I’m most interested in the outdoor market, where I can buy three pairs of the sports socks that I like for the price of two or find a new handbag. I come early sometimes, hoping to find someone that needs an extra pair of hands for the day – and I did for my first job, selling candies and biscuits from Tunisia in tandem with an old man who told me nothing about himself but everything about his children. I can’t remember his name. The market and its merchants move to different areas during the week, but I'm rooted by my school timetable.

I don’t remember markets in Montréal. Then I moved to London, a city where I have had more addresses than years to account for, and so I do for local markets. There was the butcher on Chatsworth Road who kept meat leftovers for the neighbours’ dogs, including my Poppy; the grocer who always convinced me to try a new vegetable outside of St Paul’s church; the cheesemonger who only recognised me once I asked for a cut of Scamorza in the school yard of a North London school, something to do with my pronunciation of the letter -z. Interludes too, with an earnest fishmonger in Dorking and the most welcoming of markets in Livorno. I type this and I realise that I can’t remember most of the merchants’ names, and this bothers me.

It’s a simple exercise to romanticise markets. Local products, independent shops; community meet-up; the safety of recurrence; their endurance during the Covid-19 pandemic, their outdoor setting; the diversity of their offering. The etymology of the word ‘market’ is reliable too: from the Old North French market (Modern French marché) – ‘marketplace, trade, commerce’ – from the Latin mercatus – ‘trading, buying and selling; trade; market’.

But –

a market is a place of work and trade.

Its community is a lesson in sociology, the witness of a place and its history, an inherited hierarchy, and a forward-looking timetable at the beginning of each trading day. Markets are the clockmakers of a place. They also mirror a society’s organigram: they need a system to manage human resources, providing work, health and safety regulations; their wealth is subject to demands and the impacts of the current economy or religious holidays, for examples, have on that. The tradition of markets may go back to ancient history, but contemporary markets have adapted to the workings of a capitalist economy.

I learnt as much – about both the community and the economy of markets – by heading to Billingsgate Market on Saturdays. Located on the East London docks, Billingsgate is the largest fish market in the UK: it’s said that one can find between 150 and 200 different varieties of fish on any given day. Nowadays, for 15kg of fresh seafood, about 10kg of frozen products are sold.

The first time I went to Billingsgate Market, it was over a year ago to attend a course in preparing fish with chef CJ Jackson at The Seafood School at Billingsgate. There I learnt how to fillet and skin flat fish, gut and prepare round fish to cook whole, and one of the most useful tips for those who cook fish. Always wash your hands with cold water, otherwise the oil from the fish cooks on your skin and will leave you with that fishy touch.

I also bought CJ’s cookbook, Billingsgate Market: Fish & Shellfish Cookbook, which I highly recommend to anyone who is interested in sourcing and cooking fish responsibly. The cookbook is filled with cooking tips and delicious recipes, from making fish pie and pan-fried halibut to preparing a homemade court-bouillon, and it’s a fascinating introduction to the history of Billingsgate as an institution.

The origin of Billingsgate market can be traced back to Roman times, but it was officially referenced for the first time in 1327 when a royal charter gave markets in the City of London exclusive trading rights within a 6.6-mile radius. Author and chef CJ is an excellent storyteller and would add here that the distance might sound random to you, but it was calculated so someone would be able to walk to either Billingsgate, Smithfield or Cheapside market, set up a stall, sell goods and walk back home in the space of a day. Details matter to History.

When Billingsgate was still located on Lower Thames Street, one could buy products from coal to pottery because the market was losing out to Queenhithe, which was located upstream, for seafood. At least until the year of 1699, when an Act of Parliament decreed Billingsgate Market as ‘a free and open market for all sorts of fish whatsoever’. Another CJ fact for you: Dutch fishermen were still granted the exclusive right to sell eels in recognition for their help in keeping Londoners in fish during the Great Fire.

In 1982, Billingsgate Market was moved to its current location on the Isle of Dogs. Despite its postcode being outside of the City of London, the market remains under its authority (so is Spitalfields). CJ explains the decision comes from administrative pragmatism as it enables the City of London to appoint Superintendent, who are ‘market managers’, and to streamline health and safety regulations. If you walk around Billingsgate Market, you’ll be able to see two types of officers dressed in distinctive uniforms: the Market Constables (who are not police officers, but employed by the City of London and carry security duties around the market where wheeled engines from trolleys to lorries share paths with pedestrians) and the Fisheries Inspectors.

The last time I went to Billingsgate Market was last Saturday. I arrived at 7:20am – the hall was standing loud and smelly – and merchants had started closing their stalls already. Most prices were strikethrough, some featured a new value, written hastily, and ice was melting along the hallways. Bloody puddles and steamy cups of coffee; I interrupted men in white overalls sharing a laugh a few times as I walked past them with my yellow coat. I peeked at the colours of fish scales, and I found relief in spotting a bag of clams or the recognisable gurnards. Most of the fish are not labelled with the species name, but placed in large polyester boxes so they can be transported in and out of the cold stores efficiently. It is a market for traders mostly.

Billingsgate is on from Tuesday to Saturday. The site opens at 4:30am but the first bell rings at 4:45am, at which time only inter-trading is allowed. Most merchants and porters will have arrived hours prior to that to set up their stalls, or to find work for the day in the case of the porters who are not employed by a specific fishmonger. After a busy fifteen minutes of dealings, the second bell rings. 5:00am, Billingsgate Market opens to the public. End of trading is at 8:30am, but most of the restaurateurs and business traders will have left before that time. CJ points out that they will want to be in and out before the congestion charge and traffic kick in.

After our last outing at Billingsgate on Saturday, Ludo and I spent the rest of the day cooking with and for friends. Irene, Ludovica and Valentina. I laughed enough to burn my cheeks, and you can call me out for being a romantic as I say so, but it felt good to share a kitchen with them.

We bought four Pomfret fish (whole) and one kilogram of prawns. We got four fish for the price of three as the fishmonger was keen to clear his stock; we paid £20.00 total, to give you an idea of prices. I had never cooked Pomfret before, and I found a new favourite recipe. The skin was crispy but the meat creamy; a sweet, vanilla like coating, one to mop off the tray with bread. Recipes below.

Tuna and cannellini beans salad for starter:

1 can of cannellini beans, drained

2 small cans of tuna, oil preserved

Half red onion, thinly sliced

A generous handful of parsley, chopped

In a large salad bowl, combine and mix the ingredients together.

Prawns and lemon pasta for primo:

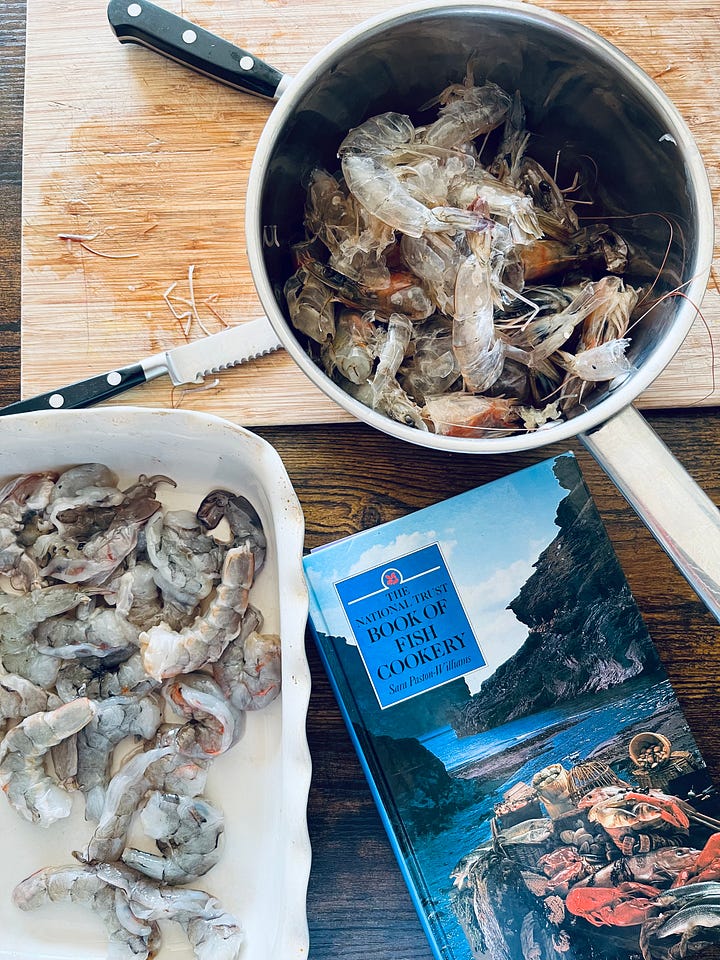

This is Ludo’s recipe and, to be honest, a long story that blurred overnight. I can tell you that the pasta dough was made of semola flour and water (lukewarm), roughly cut lengthwise, and cooked in a homemade broth (made with the prawns’ tails and heads). Ludo and Valentina butterflied the prawns, and I loved watching their skin colour in pink and curl up inside the pan; they also kept two prawns whole per person to top up plates. They sprinkled lemon zest on top of our plates for a citrusy bounce back against the pasta.

Baked Pomfret fish, served with a side of insalata Pantesca, for secondo:

For the fish and its lemon oil:

4 Pomfret, whole, gutted and scaled

a sprig of rosemary, left whole

1 bunch of spring onions, roughly chopped

30g salted butter

4 garlic cloves, grated

3 tsps. paprika

1 small peperoncino, crushed

4 tsps. oregano, dried and grounded

1 tsp marsala, grounded

125ml olive oil

juice of 2 limes

1 tsp tomato purée

Start with preparing the fish to bake whole by scaling the Pomfret, gutting it, and cutting its fins. Stuff the fish with rosemary sprigs and place them on a baking tray (with some baking paper lined underneath). Preheat the oven to 200C fan.

In the meantime, make the lemon oil. Crush and mix the paprika, peperoncino, oregano, and marsala together. In a milk pan, melt the butter over a medium heat. Add the garlic and wait until fragrant before removing the pan from the heat. Stir in the grounded spices, olive oil, lime juice and tomato purée, mixing continuously until you’ll have a homogeneous paste.

Brush the lemon oil over the fish (generously, you’re after a glossy look) and return them on the baking tray. Sprinkle the sliced spring onions on top. Bake for 20 minutes, or until the flesh flakes easily under a fork. Switch the oven to grill and keep cooking the fish for another 10/15 minutes, or until the skin is crispy enough to your taste. (Remember that a grill setting makes any oven moody; stay next to it and check on the fish often.)

For the insalata Pantesca:

potatoes, skin on

tomatoes, roughly chopped

red onion, thinly sliced (lengthwise)

oregano, dried (plenty!)

capers, roughly chopped

olive oil

(a side note: the traditional salad from the island of Pantelleria includes pitted black olives, but I dropped the jar on the floor while making dessert earlier in the morning.)

Slash the potatoes lightly and boil them (but keep them firm enough to hold the salad together). Leave the potatoes aside to cool, then peel and chop them (keep them fairly chunky).

In a salad bowl, combine all the ingredients and mix well.

Dessert, anyone?

My current local market takes place on Saturday too. There is one greengrocer and a few bakers, a florist and street food stalls. Two French men sell sandwiches out of a truck, La Roulette by Magica, and there I ate a bomb of a goat cheese, pickled rhubarb, and wild garlic bun once. The chefs and owners are called Guillaume and Jean-Charles.

Markets are about the people who nurture them – so is food. I’d love to hear about your market stories and recipes.

Margaux

P.S. The Seafood School at Billingsgate has sadly closed, but CJ Jackson is still hosting courses. I can’t recommend spending a few hours with CJ enough. More information here.

Thanks for being here! This newsletter comes out every other Thursday, and you can give it some love by subscribing below or forwarding it to a friend.

Another way to support my work is to buy a copy of my debut novel, The Yellow Kitchen. You can find the paperback edition at your favourite bookshop, or on the Onion Papers affiliated shop.