La Vendée

a French coastal department made of marshes and groves, folklore and displacement; recipes for pasta with dandelions, brioche, escargots and sardines on toast

Last week, I returned to la Vendée. The history of my family is as such that younger generations have had little access to the archives of our name, however the western department of Vendée is a connection point. When I was a child, I spent my summers in Les Sables-d’Olonne, a city famous for its estuary and port, a holiday destination and the house where my paternal grandfather lived. A retired footballer (midfield player between 1948-1955), Roger wore pink v-neck pull-overs and drove an old polo car with a heavy hand on the gearshift. I spent the months of July sitting next to him in his study, amongst the smell of cigarillos and old-fashioned striped wallpaper, watching the tour de France. Vendée is also where my mother lives now, but in a ground-floor house located inland, next to vineyards.

Returning to Vendée was an experience of displacement. Intellectually, a visit to my mother in a radically different place from where I grew up and once shared a daily routine with Maman, the hyper-urban northern suburb of Paris. Vendée, a place where I can still hear my grandfather telling stories at dinnertime, a man whose death has silenced since. His sofa, wrinkling and made of leather the colour of camel, or where I remember having my first political awakening, quite literally. I had woken up with a start at the sound of adults shouting in the room, the large TV showing the presidential election results. It was the year of 2002, or the first time one of the Le Pens made it to the second round; I often wonder what Roger would say about our contemporary days, but I don’t have a clue. My mother’s house, where I stay but I have never lived, reminds me that my childhood home has faded over time and that melancholia blossoms between us. A physical displacement, too, since Vendée is a rural department where moving around requires a car but I don’t have a driving licence. The landscape stretches flat and far away, the sky is painted with watercolours, flat wheat fields and I miss the sight of sunflowers from summertime. Groves, cultivated land, industrial shops, and the interruptions of small villages where pizza self-service machines and bakeries share a clientele; the radio plays in the background, and Tété sings in favour of Autumn.

Mornings in Vendée are eerie. The mist is dense, the result of a stormy weather set between ocean and countryside, shedding oak trees and high pine trees popping up like needles. A palette for grey and lilac thread the early morning hours and the air is cold; I draw in, inhale, the environment is fragrant between woodlands, ploughing and soil.

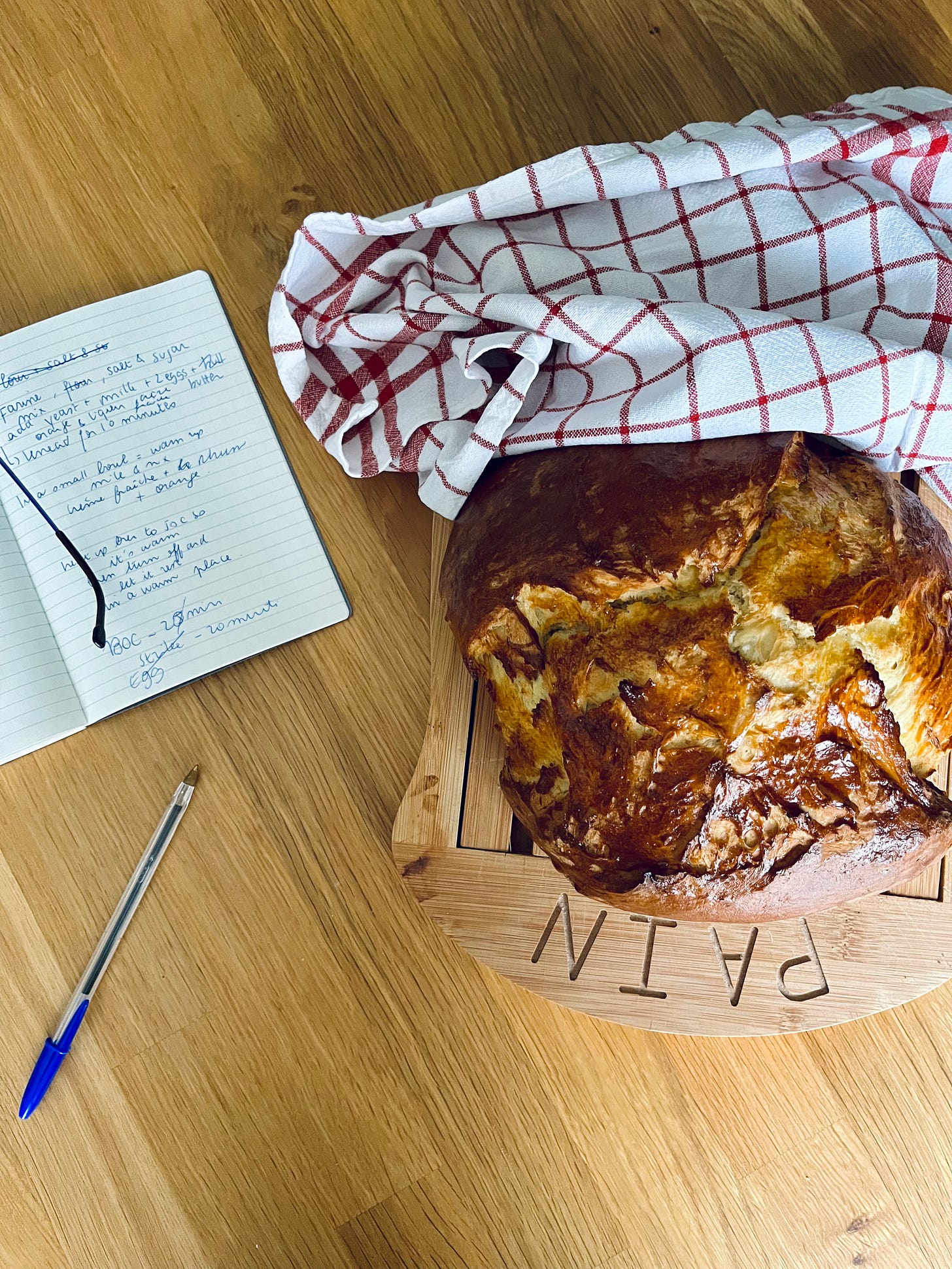

France is the land of breakfast, and Vendée doesn’t disappoint. ‘La gâche vendéenne’ is denser than any other brioches, the shape of a rugby ball and the crust generous, its recipe includes crème fraîche. The top is scored and the dough shouldn’t be fitted inside a mould when baking. In 2013, the gâche vendéenne was granted the IGP – European protected geographical indication – for its production and my mother tells me one of the two bakeries in the village where she lives has lost its label IGP. They advertised ‘gâches’ but they didn’t use crème fraîche, rumour has it. The making of this kind of brioche vendéenne can be traced back to the Middle Ages and was originally prepared for Easter: kneaded during Easter Friday, baked on Saturday morning and consumed upon returning from mass. These days the gâche features on breakfast tables and during the goûter (/snack time between lunch and dinner); it’s delicious on its own, dipped into coffee, while some might want to add a nugget of butter or other spreads on top. Gâche is also served at traditional weddings when the brioche is carried over a large wooden board by the newly-wed couple and the ‘danse de la brioche’ is performed, before the crust is shared between the guests. The wedding edition weighs a mighty 10+ kilograms.

Reader, will you marry me for a piece of gâche? You’ll need:

25g fresh yeast, diluted in approx. 3 tbsps of warm (oat) milk

550g plain flour

100g sugar

½ tsp salt

2 eggs, plus one yolk for egg washing

100g (oat) milk, lukewarm

2 tbsps crème fraîche

1 tbsp orange essence

1 tbsp rhum (optional, can be replaced with vanilla or the liqueur of your choice)

100g butter, softened and cubed

Start with activating the yeast. Warm up the milk, break the yeast and mix with a fork. Set aside for 10 minutes.

In a large mixing bowl, pour in the flour, salt and sugar. Mix and shape a mountain with a hole in the middle. In a separate bowl, warm up the milk lightly, then mix together with the crème fraîche, orange essence and liqueur of your choice. Pour into the flour, break the two eggs and mix with a wooden spoon. As a homogeneous dough forms, start adding the butter and knead as you go. Keep kneading for 10 to 15 minutes, until you obtain an elastic dough.

Place the dough inside a humidified kitchen towel. Tuck it inside a bowl and let it rest for 3 hours, or until it has doubled in size.

Preheat the oven to 180C, fan. Cover an oven proof tray with baking paper and place the dough, shaped in a large log, on top. Egg wash the dough and bake for 25 minutes. Score the dough and bake it for another 20 minutes.

The department of Vendée was created on 26 February 1790. Its history is marked by the violent Vendée wars, which took place during the French revolution. The civilian conflict opposed republicans (the ‘bleus’) and the monarchists (the ‘blancs’) and the final estimation counts around 200,000 deaths. Needless to say that such an event has shaped the culture and making of the area, yet I hadn’t grasped some of the signs before visiting the ‘Mémorial de la Vendée’ for the first time last week. Located in Les Lucs-sur-Boulogne, the monument stands in memory of those who were shot, drowned, guillotined and burnt alive during the period of terrors.

The memorial is built in the form of a long corridor along which various letters of orders are framed. Infernal columns and registries of victims, petitions from armies to put a halt on blood baths and decrees that erase Vendée from history books. There is a strong smell of hay and wooden sculptures acknowledge victims physically; I found myself moved as I walked across the building. On the other side of the memorial, there is the museum of Vendée. There I learnt that it’s far more complex than a case of a dichotomy between those who opposed the separation of church and state, in favour of the monarchy, against those who supported the republic. The insurgents were landowners who fought against rising taxes, anger powered by repetitive drought and a textile industry in crisis, fears for their family’s future and well-being. It was a case of civilians defending their rights against political totalitarianism, a case for a right to live in dignity that was fraught and silenced with repetitive acts of violence performed on bodies – history moves in circles. The large Western marsh harrier can often be spotted flying low and flat in the sky of Vendée, in search of prey.

A consequence of periods of scarcity, escargots became a staple of French cuisine. They sizzle with butter, garlic and parsley, served straight into their shells in Parisian bouillons, whereas their preparation varies across the country. In Vendée, specifically, they come in a ‘sauce aux lumas’, the thickness similar to a béchamel, a creamy symbiosis between flour and butter and milk, with an addition of shallots, parsley and garlic. The result is tender and easier to consume for those who might have concerns about eating chewy snails.

From the cuisine of Vendée, one would expect Mogettes, the white beans that were imported from Mexico to France, served with ham or sausages. The climate in Vendée suits its agriculture and most recipes are made to be cooked for large quantities, spoons dive into deep saucepans. Vendée is a community-led department, where monthly fairs and weekly markets make up for most of the social life. Fairs tend to be thematic, like donkeys in Fontenay-le-Comte or horses in Saint-Gervais, whereas markets feature rich displays of fish, meat, vegetables, dairy and baked products.

Last week was also the occasion to go foraging somewhere new. The ground in Vendée is wet – vivid green colour, reeds and mushrooms, many of them – wild, the nest of bugs I have not seen anywhere else. Ludo had an omelette with chestnut bolete for breakfast and we discovered a new species that is called, appropriately, Camembert brittlegill (it’s edible as well!). We walked between rain showers and dandelions grow in abundance at this time of the year, so we made pasta for dinner. Anolini, the grassland Vendéens edition, filled with dandelions, ricotta, marjoram and lemon zest.

For the pasta dough:

00 flour

Eggs

It’d be counter-intuitive to give proportions here as it’s important to start kneading to see how many eggs you might need. ‘À vue d’oeil,’ my grandfather would say.

For the filling:

Dandelions

Ricotta

Lemon Zest

Marjoram

S&P

Measurements to be adapted in function of how much pasta you’re making.

For the sauce:

Passata

A squeeze of tomato purée

Onion, peeled and cut thinly

Fresh basil

1 tsp of sugar

S&P

Start with making the filling. Remove the roots and wash the dandelions. Bring them to the boil with the juice of half a lemon. Cook until tender (approx. 30 minutes). In the meantime, drain the ricotta by placing it inside a cloth (something spongy) for 10 minutes. Drain the dandelions well and cut them thinly. In a bowl, mix the ricotta, dandelions, lemon zest and marjoram together. Add salt to taste (remember that dandelions are on the bitter side).

Next, make the pasta dough. On a wooden surface, build a volcano with the flour and crack a first egg in the middle. Knead, adding more eggs and flour as you go, working the dough with your hands until you have a homogeneous preparation. Once the consistency is holding together, start passing the dough through a pasta machine. You are looking at making rectangular sheets. Don’t go too thin so the pasta will be strong enough to hold the filling.

Start slow-cooking the pasta sauce. Golden the onion, add the passata, tomato purée and sugar. Reduce to a low heat and leave the sauce to simmer.

In the meantime, assemble the anolini. Stretch the pasta sheets on a wooden surface and place small nuggets of filling mid-way through the sheet. Fold over and pinch the two sides of the pasta sheet together with the tip of your finger (you can use egg white if you need something sticky to help your case). Cut with either a pasta cutter wheel or a round pasta mould (it’s like stamping dinnertime!).

When the anolini are ready, add a few leaves of fresh basil to the tomato sauce and bring a separate, large pot of salted water to the boil. Cook the pasta until they swim back at the surface (approx. 3 minutes) and transfer them into the tomato sauce. Coat the pasta and cook altogether for another minute or so.

Vendée owes its name to the eponymous river and the climate is humid. A department where religion has had authority – still does, for what I observe – spirits are feared and the ocean has been playing a significant role in its development, in terms of folklore and economy. In Les Sables-d’Olonne, where the tides are voracious, the church at the end of the coastline is dedicated to Saint-Nicholas, the patron of the fishermen.

The port of Les Sables-d’Olonne was the first one in the country under Louis XI and its modern, commercial evolution was built in 1964. Sable means sand in French. Les Sables-d’Olonne is also where the Vendée Globe, the greatest solo and non-stop sailing race around the planet, starts and ends every four years. The name Michel Desjoyeaux resonates, a snack of whelks; oysters from Noirmoutier and mussels from L’Aiguillon-sur-Mer, moules-frites, always, and the sardines are from Saint-Gilles-Croix-de-Vie. Other than the fishing of fresh sardines, the business of tinned fish plays a consequent role in the economy of the department.

A working from home lunch staple in my kitchen is sardines on toast, eaten while standing before the counter. Tinned sardines, the colours of my France when I’m abroad; always preserve the oil from the can as it’ll come to good use later, I’m reminding myself too.

1 can of sardines, flavour of your choice but simple oily ones work best here

1 tbsp soy sauce

Juice of half a lemon

1 tsp miso paste

½ tsp paprika

2 slices of bread

A sprinkle of oregano

In a bowl, mix the sardines, lemon juice, soy sauce, miso paste and paprika together. You’re after the texture of a thick mash. Spread over bread and sprinkle oregano on top.

Margaux

In memory of Papi Roger, who died in November 2016.

If you enjoy The Onion Papers, please consider hitting the subscribe button below and feel free to share this newsletter with anyone who might enjoy it. Thank you, à bientôt!

I was just thinking I wanted to go back and find your gâche recipe -- thank you for this!