‘Nothing moved except the mirage.’ – Minor Detail by Adania Shibli

‘Once upon a memory, at the far end of the Mediterranean Sea, there lay an island so beautiful and blue that the many travellers, pilgrims, crusaders and merchants who fell in love with it either wanted never to leave or tried to tow it with hemp ropes all the way back to their own countries.’ – The Island of Missing Trees by Elif Shafak

‘Lucrezia is taking her seat at the long dining table, which is polished to a watery gleam and spread with dishes, inverted cups, a woven circlet of fir.’ – The Marriage Portrait by Maggie O’Farrell

‘Seeing comes before words.’ – Ways of Seeing by John Berger

The four quotes above are the opening sentences of some books I read recently, or that I’m currently reading in the case of Shafak’s Island of Missing Trees. I spend an unmeasured amount of time reading the first sentences of novels. On the one hand, I love them for how much they can hold: sometimes tender like a welcome hug, bracing words before a story can be told, or once so sharp as a call for attention from the author to the reader. On the other hand, a quick online search leads me to find countless articles about the ‘10 books with the best opening sentences’ or blog posts on how to write an efficient opening sentence. This exact pressure we, and I’m including myself here, exercise over the first sentence of a book as readers, critics and writers is symptomatic of how quick we’ve become at forming opinions as a society.

Perhaps I’m nosy, but it’s near impossible to read a first sentence printed in a book and not wonder how the initial, first sentence read. What was the origin idea? When did the idea root, and what was the seed before that? Who or what inspired it? The opening sentence is the ambivalent parent of a book – it has become the door for readers to unlock their way in, yet it most likely wasn’t the first sentence written towards the completion of the final project. This is a great reminder about the power of storytelling to deconstruct systems: stories echo one another, either in harmony or discordance, and storytelling bonds our experiences together.

As I was writing this, I paused, and I tried to think about what was the very first sentence of my debut novel. I have notebooks from years ago, in which I sketched characters from the novel, but no actual sentences that fell constructed with the intention to draft a manuscript. I opened the oldest file I’ve stored on my laptop, which has a different title, and I didn’t recognise the novel’s voice. Then I opened the earliest document I could trace with The Yellow Kitchen as a title – ‘Our kitchen was narrow like a spiderweb’ – and I spotted a ghost. Still, I’m not convinced one of these sentences is the origin of the novel; in fact, if you ask me now, I’d tell you that it started with a sentence I caught from a conversation between two women sitting next to me in the Tube years ago. It was way-passed my bedtime, so that’s an unreliable fact about how I came to write the novel. Except that it isn’t less accurate than any of the other ‘first sentences’ I wrote, because beginnings aren’t about singularity – stories feed one another, and contextualisation matters.

And contextualisation isn’t interpretation either. If we look at the four opening sentences above, which are a random selection made of the books piled on my desk, they each hint on the story they’re about to tell. If I analyse them now, I’d do so with the book at the forefront of my mind – remember that I read each one of them in the last five weeks or so – and it’d be an echo of my reading of that book. That is a first sentence in context. The sentence in consideration of the unfolding plot and the publishing history of the book (political context, language, reception). However, if we extrapolate the same sentences and you tell me what you think about them, assuming you haven’t just read the books yourself, you’d give me a spontaneous interpretation of what they mean or intend to signify. To a certain degree, you’d be branching your version of a story onto an existing story.

There is more to say, notably about morals and retelling vs appropriation, and we’ll discuss more as we get to think and eat together over the weeks. The reason I’m telling you this today is because you’ve come to Kneading Club, and I want you to feel at home here. I want us to slow down before forming a judgement about one another and for us to remember that there can be new beginnings to existing stories. And that this applies to novels and to life stories, as long as we pay attention and that we listen hard enough to reconsider what we had taken for granted, to hear other’s life stories as they mean to tell them. As long as we accept that there can be other beginnings than the ones that matter to our immediate self.

‘I think the hardest thing for anyone is accepting that other people are real as you are. That’s it. Not using them as tools, not using them as examples or things to make yourself feel better or things to get over or under. Just accepting that they are absolutely as real as you are.’ – Zadie Smith

I discovered the above quote via Nitch last week. You’ll find further readings and resources at the end of this newsletter.

This week in the kitchen, we’re making crêpes. They’re a favourite for Sunday lunch in my home because they’re such a delicious treat and you can make them in no time and add any toppings you fancy that day (/whatever is in the fridge, so you don’t have to go to the shops). And, most importantly, you can cook lunch and dessert with the same batter.

recipe notes:

*I love to add caraway seeds and rum to my crêpes preparation. A little thunder in their cloud! You don’t have too; see below for alternatives.

*I make crêpes with water instead of milk or other dairy alternatives. I find them lighter and more accommodating for savoury fillings this way.

*I also use white flour because this is what I’ve in store in my kitchen, and this makes the crêpe more versatile. The traditional galettes from Brittany are made with farine de sarrasin (buckwheat) and square-shaped – and delicious with a bowl of cider.

for four large crêpes:

120g white all-purpose flour

160g water

2 eggs

1 tbsp rum (or vanilla extract)

1 tbsp caraway seeds (or none, or other seeds you like)

A pinch of salt

In a large bowl, mix the dry ingredients together. Add the water slowly, mixing continuously with a whisk. If you aren’t in a rush, leave the preparation to rest for 20 minutes.

Now I must warn you that there is a rumour about the first crêpe never cooking properly. The key is to heat the pan high enough before you’ll start making the first crêpe. Then drop a knob of butter and make sure that it spreads throughout. With the help of a ladle, add some of the preparation and let it cook (until the borders will start levelling up). Flip the crêpe around and cook it on the other side.

Over to you for the filling. My favourite at this time of the year is creamy mushrooms, for which I simply mix some sliced chestnut mushrooms, chopped parsley and oat cream in a casserole (if the mushrooms sweat too much, add a tablespoon or two of semolina). Other ideas include goat cheese, spinach and honey; sun-dried tomatoes and mozzarella; creamy asparagus; smoked salmon, crème fraîche and dill.

Will you let me know how you end up eating your crêpes?

Margaux

further readings and resources:

Adania Shibli for the Guardian: shedding light on her work and the power of linguistics and erasure.

UK-based templates to write to your MP and call for an immediate ceasefire in Gaza.

If you’ve the means, consider making a donation to Medical Aid for Palestinians. MAP is on the ground in Gaza, stocking hospitals with essential drugs, disposables, and other healthcare supplies.

A Gathering: Palestinian poems with and for the now, via ArabLit.

I recommend any of the books mentioned above: Berger to see; O’Farrell to escape in time; Shafak for a touch of magical; Shibli to learn, contextualise and take actions.

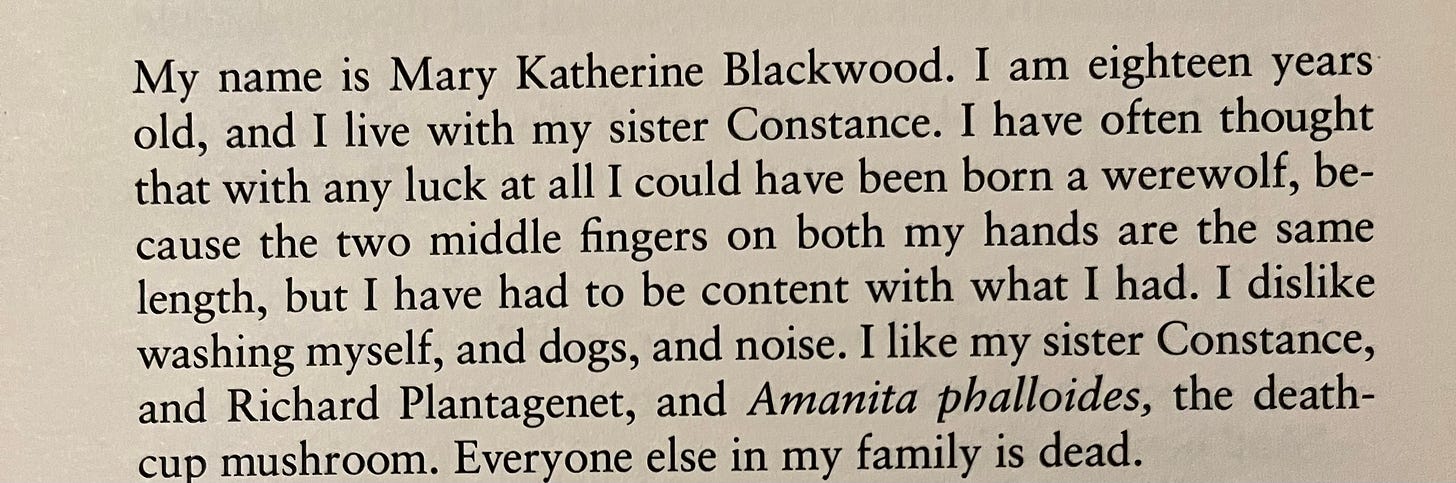

A long-term beloved book opening:

Thanks for being here with me. You can also read more about my novels here.

To join Kneading Club and receive weekly recipes and notes on craft, upgrade your subscription to a paid membership below. You can unsubscribe any time: