Cucina Pantesca

sharing a meal with you to conclude this August interlude in Pantelleria; reframing compassion with M.F.K Fisher, summer ends

You’re walking next to me. I want to be reassuring when I say that the road is short, but uphill. I catch you squinting your eyes and I acknowledge that it’s amazing to see rosemary plants grow in unexpected places like that. Green needles pop between rocks, I smile. My skin is stretched, salt crystals snow over my eyebrows; you pick a wild fennel stem and lift it up, under your nose. Rain might be a rare phenomenon, but high levels of humidity gift the island a variety of plants and vegetables. We must put the fish and the cheese in the fridge now, I remind you as we take a turn.

‘We’ve arrived,’ I confirm and I sigh. Perhaps you do too, but I can tell you that I wanted my sigh to be loud and relieving before I was strangled by the thick, scorching air. We’re here together and I don’t know where is home for you, even if you’ve a place that you call home; I don’t dare ask, but I look at you and I assume that we share a longing for shelter. Our quotidian has made us sedentary people and a house is how we theorise our lifestyle. Ouch, I shiver as I think about the implications of a word like lifestyle.

I’m digressing, you bring me back with a comment on the house walls. You speak brightly; they’re pink! The house is square-shaped, the roof is painted in white. We’re silent again and I think that you look beautiful, standing on the paved patio of this pink house overlooking the sea at the bottom of the valley. The sheer curtains draw lines with shade for ink over your body. Time crisps like an old tv that has lost connection with its antenna – I look at you and I look at the house in front of us and I think about those who lived here before us. We enter the dammuso and you sound surprised. You’re right though, it’s chilly inside. I tip you to check how thick the walls are, knocking one and hurting my knuckles. They’re drystone walls and I can be brusque when I’m hungry.

I cut some Tumma and grab sundried tomatoes. We must snack before cooking and I’m glad that you welcome the idea. I wait for you to bite into a piece of cheese before I explain that the Tumma di Pantelleria is a soft cheese made from raw cow milk. Some things shouldn’t be spoiled. There are no sheep on the island.

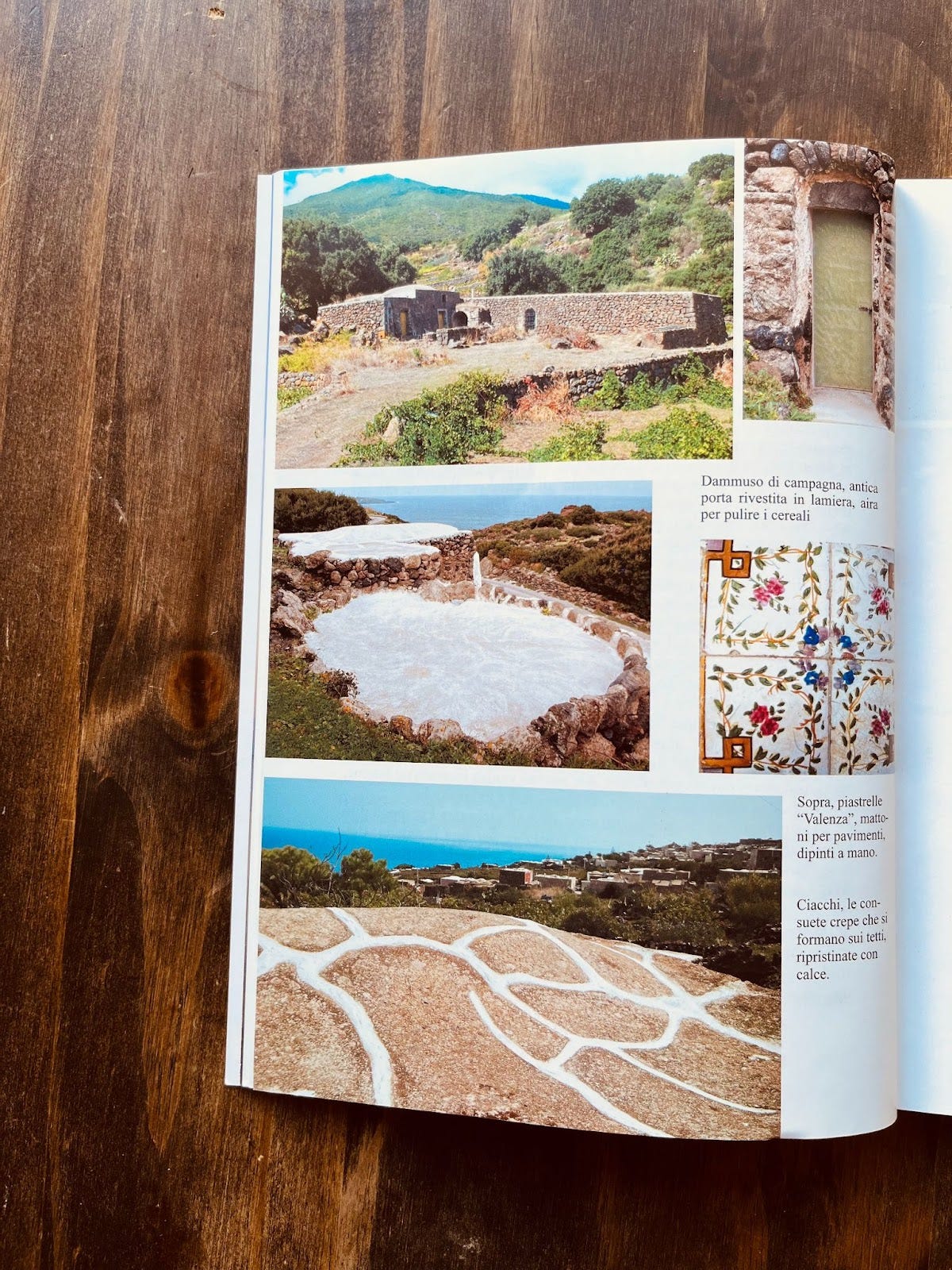

The Dammuso is the typical house found in Pantelleria. Its architecture is a testament of the socio-cultural development and the location of the island. I wrote about this in greater detail in the previous edition of TOP: the distance between the island and the mainland, its geology and weather patterns, means that it can be hard to find everyday resources. Dammusi are rooted in the economy of the island – a communal home in conversation with its environment.

There are traces of dammusi as far back as prehistory. The foundations are made with volcanic rocks and the dome roof is waterproofed by mixing plaster and local tuff rock. There are three rooms only in a traditional dammuso: the main room, a living space where a stove is available to cook; at the end of that room, there are two alcoves with lace curtains attached, a small and a master bedroom on each side. The walls are thick enough to provide isolation, so the house is cool in summer and warm in winter.

The Dammuso is self-sufficient and energy proficient. Its functioning was revolutionised during the Punic-Roman period, when a cistern was installed underground and connected to the roof to collect rainwater. After over 2,500 years, these cisterns are still used for domestic use around the island, and I was told that eels were thrown in them (alive!) to keep the pipes clean.

The cuisine of Pantelleria is at the crossroads of Sicily and north Africa, rich with herbs such as oregano, mint and parsley. Capers add an aftertaste to most dishes and plates of pasta are dressed with the island shores: gamberi and breadcrumbs, sea urchin salsa, anemone, limpets. Tomatoes, courgettes and aubergines mature with a juicy flesh and leftover vegetables make fantastic Ciaki Ciuka (a ratatouille, but Pantelleria style!). Honey is made with mosto, a juice squeezed from grapes, including seeds and pulp, and jam with pepperoncini – both preserves are served with cheese. For those with a sweet inclination, you may want a mouthful of baci panteschi, or ricotta farfalle biscuits coated with chocolate.

An insalata Pantesca to start:

potatoes, peeled, boiled, cooled and squared

tomatoes, roughly chopped

red onion, thinly sliced

capers

oregano

olive oil

white vinegar

salt

In a large serving bowl, toss all the ingredients. Mix and dress with oil, vinegar and salt.

(I also shared recipes for Pesto Pantesco and ravioli alla Pantesca in the last newsletter, Dancing with Medusa in Pantelleria.)

Now comes my favourite: the cuscus Pantesco. The main difference between the couscous in Pantelleria and the dish as cooked in Morocco, Tunisia or Spain, is that broth, fish and fried vegetables are mixed together. The secret I wish I had found out earlier is that you should add plenty of tomatoes to your broth.

The common ingredients include grouper fish, chilli, onions, garlic, parsley, oregano, tomatoes, aubergines, courgettes, peppers (of two different colours), potatoes, carrots, white wine, olive oil and salt. It’s a versatile dish though, and when I’m in the UK, I tend to cook my cuscus with aubergines, courgettes, peppers, sea bream and prawns. It works well as a vegeterian couscous too.

Regardless of which veggies or seafood you’ll pick, the key is to prepare the couscous with your hands before cooking it, so it’s fluffy and airy instead of looking like a blobby porridge for dinner. As follows: in a large bowl, work the couscous with your fingers and a few drops of water for approximately 10 minutes. The aim is to separate the couscous with your fingertips. You will need it to be slightly moist, but you don’t want to drown it. Leave the couscous to dry under a kitchen towel for 20 minutes. Transfer the couscous into a large, flat bowl and add a ladle of broth (or more, depending on how much couscous you’re making; it should be hydrated, but not drunk). Add dried oregano and cover again with the kitchen towel. Leave aside for 30 minutes so the couscous cooks slowly in the broth.

Fry the vegetables and the seafood, adding ladles of broth and seasoning as you wish. Stir in the couscous and mix together. You might want to add more broth if you like yours on the wet side (I know that I do).

Serve plates of cuscus with side bowls of broth.

We sit down with our food and we act hesitantly. We’re still getting accustomed to each other, yet sharing a meal brings proximity. I’m worried about the silence that settles in and that you might not like the food, so I fill the gap by telling you about this book I love: M.F.K. Fisher’s How to Cook a Wolf.

‘It is all a question of weeding out what you yourself like best to do, so that you can live most agreeably in a world full of an increasing number of disagreeable surprises.’

– How to Cook a Wolf by M.F.K. Fisher

The first edition of the book was written during World War II, in 1942, and as a guide to cook despite violence, ration cards, pains and empty pantries. The edition I have home includes a new introduction from the author (dated 1951), which features Fisher’s trademark wit: she added some recipes that are as decadent as, she specifies, requiring 12 eggs! ‘But even the wolf, temporarily appeased, cannot live on bread alone’, she justifies.

I pause my eating to detail that I cherish this book because it’s hopeful yet believable. If you read How to Cook a Wolf, you could be making Eggs in Hell for your enemy or spoon into a Date Delight. This is a compassionate book – pragmatic and human. If Fisher is able to feed either one or many with her writing, it’s because she cares for the ingredients but not much else. She is focused but not restrictive; open-minded to what type of cook you might be(come). It doesn’t matter to Fisher if you buy fresh or frozen peas, if you salt your onions before or after stirring in the tomato sauce; she wants you to cook and to eat your egg – ‘to existing as gracefully as possible without many of the things we have always accepted as our due: light, free air, fresh foods, prepared according to our tastes.’

I take another mouthful of cuscus; it really tastes like summer in Pantelleria. It’s a hot and demanding dish; unique, a haze. I notice your frown and I wonder if you’re following me so I opt for honesty. While I know our reality sets us apart from the one of Fisher’s wartime America, I’m afraid to say that her hunt for the wolf is relevant again. July was the hottest month ever recorded on Earth and this terrifies me. I’ve said it. And, if I may continue, what really worries me is that in a time of societal collapse and violence, communities will be broken up and divided. Not one government likes to have its people unite because united people upturn governments.

I eat rapid forkfuls of cuscus. I sense you’re looking at me.

You remind me of what I told you earlier. When the water runs dry in the cistern, ricotta cheese is matured with seawater instead of fresh water. I look you in the eyes. With privilege often comes inertia and individualism, modern obstacles to difference. There is no right way to navigate activism – some of us might have a skill to lend or time to volunteer, others may have a platform to relay information or money to donate – but it always starts with doing and strengthens with uniting in doing. Fisher says it better than I do: cooking or hunting the wolf is not about following an old and authoritative method, but about adapting before a change. A disruption that considers its surroundings with empathy.

‘I cannot count the good people I know who, to my mind, would be even better if they bent their spirits to the study of their own hungers.’

– How to Cook a Wolf by M.F.K. Fisher

I ask you to forgive me the basic image and to think of tidal schedules. When one coastal area is experiencing a low tide, the other part of Earth is seeing a high tide. I cooked this meal today so you’d look at me and I’d look at you, you know, to choose compassion. We stand up to clear the table: silence can be really hard to break.

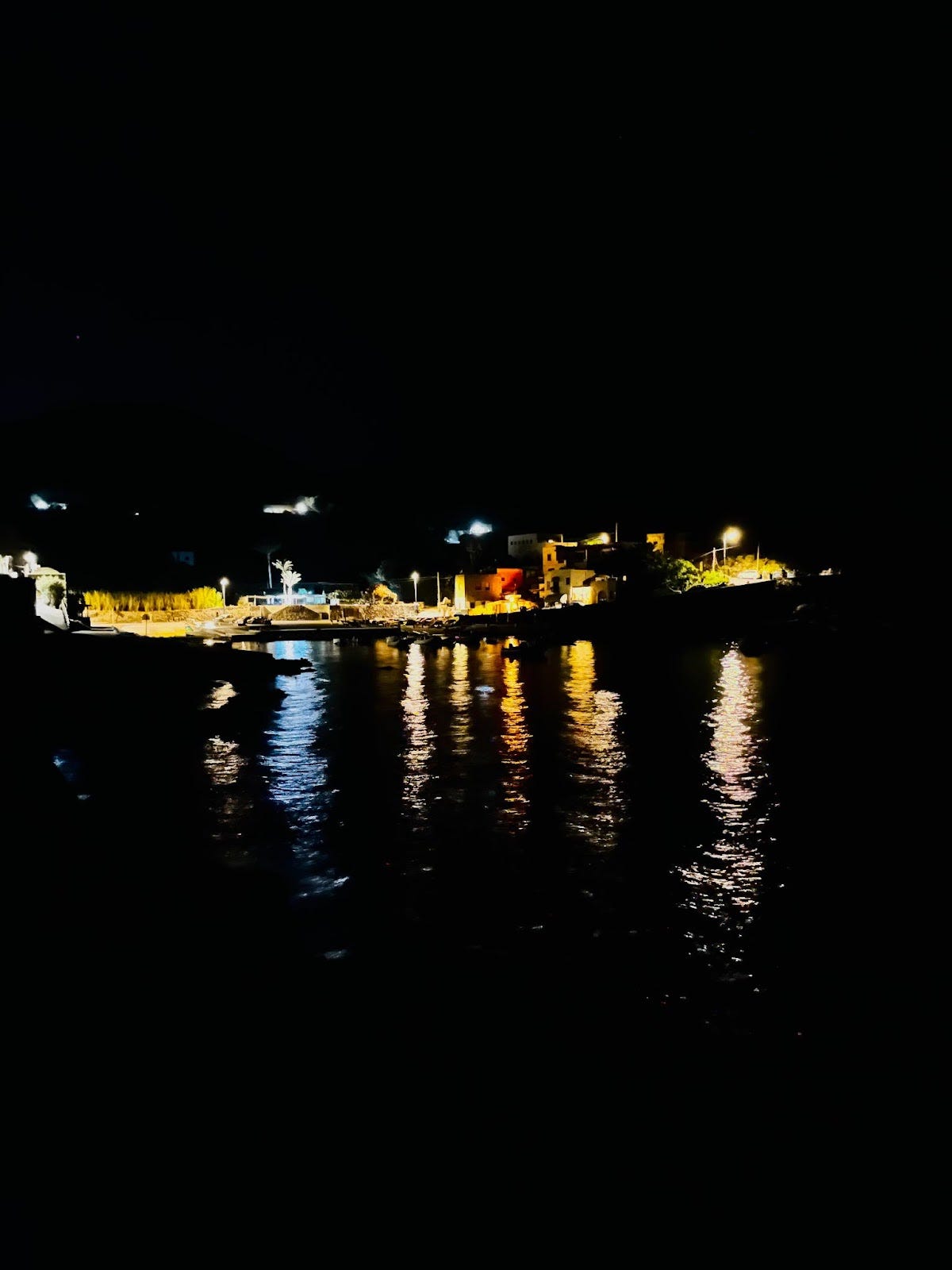

The night has fallen. We head back outside and we sit on the bench that is carved into the low wall at the front of the house. Called ‘ducchene’ in Panteschi, these are another typical feature of the dammuso home and are made of hard stones, covered with tiles, and designed to reunite outdoors when the temperatures cool down.

I fill two glasses with passito wine and place a plate of treats between us. Traditionally these should be plain sesame biscuits, but I’m going to elbow Fisher and twist that recipe with tahini biscuits, coated with pistachio nuts and black sesame seeds.

for the dough:

50g unsalted butter, soften but not liquid

50g brown sugar

120g 00 flour

1 tsp baking powder

1 tbsp vanilla extract

1 tbsp tahini

1 yolk (preserve the white for the coating)

In a large steel bowl, mix all the ingredients with your hands. Knead for 10 minutes or until you’ll have a homogeneous dough. Cover the dough with a kitchen towel and leave it to rest for 15 minutes.

for the coating:

25g black sesame seeds

25g pistachio nuts, roughly chopped

egg white, preserved from the egg above

1 tsp tahini

Mix the ingredients in a bowl.

method for the biscuits:

Preheat the oven to 180C fan and prepare a tray with baking paper. Roll a ball of biscuit dough between the palms of your hands, then into the nut coating. Flatten the dough with your hands and lay each biscuit on the baking tray.

Bake for approx. 15 minutes or until the biscuits are golden. Remember that they will get firmer as they cool down.

We stand next to each other now, and I confess that I’m going to miss summer when the season will slip away, south of the globe. You nod: the sunset will happen before 08:00 p.m. by the end of the month. I put on a playlist –

– will you dance with me?

Margaux

This newsletter comes out every other Thursday, and you can give it some love by subscribing below or forwarding it to a friend. This really makes a difference, so thank you for being here with me.

Another way to support my work is to buy a copy of my debut novel, The Yellow Kitchen. You can find the paperback edition at your favourite bookshop, or on the Onion Papers affiliated shop. <3