Between Seasons, Simmering Broth

creativity and resourcefulness; discovering Maria Bartuszová at the Tate

Days are stretching. It’s bright enough for me to see the corner of the street when I leave the house in the morning, and London plays its usual trick of painting the sky pink, orange, lavender as if to say sorry for the stress it caused yesterday. Sunny on Wednesday, an order of white wine with dinner, a rainy run on Thursday morning; frogspawn appears in ponds and it’s really cool to watch. February, a short month between seasons, a time when Londoners don’t know how to dress anymore, nature is regenerating, and I seem to be consistently late for something.

As much as I’d like for it to be the case, I rarely find cooking relaxing. I feel fulfilled when I cook for someone I love, I get energised by testing a new recipe, I have fun when I hang out in the kitchen with a friend or at a party (I’m on team dishwashing). Leave me alone and I’ll be eating sardines straight from the can for lunch, while I master the fine art of boiling eggs with impatient manners, so they chew oddly, both cooked and undercooked at the same time.

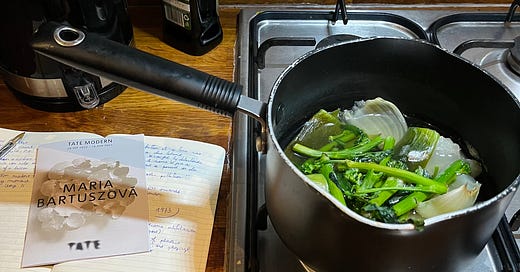

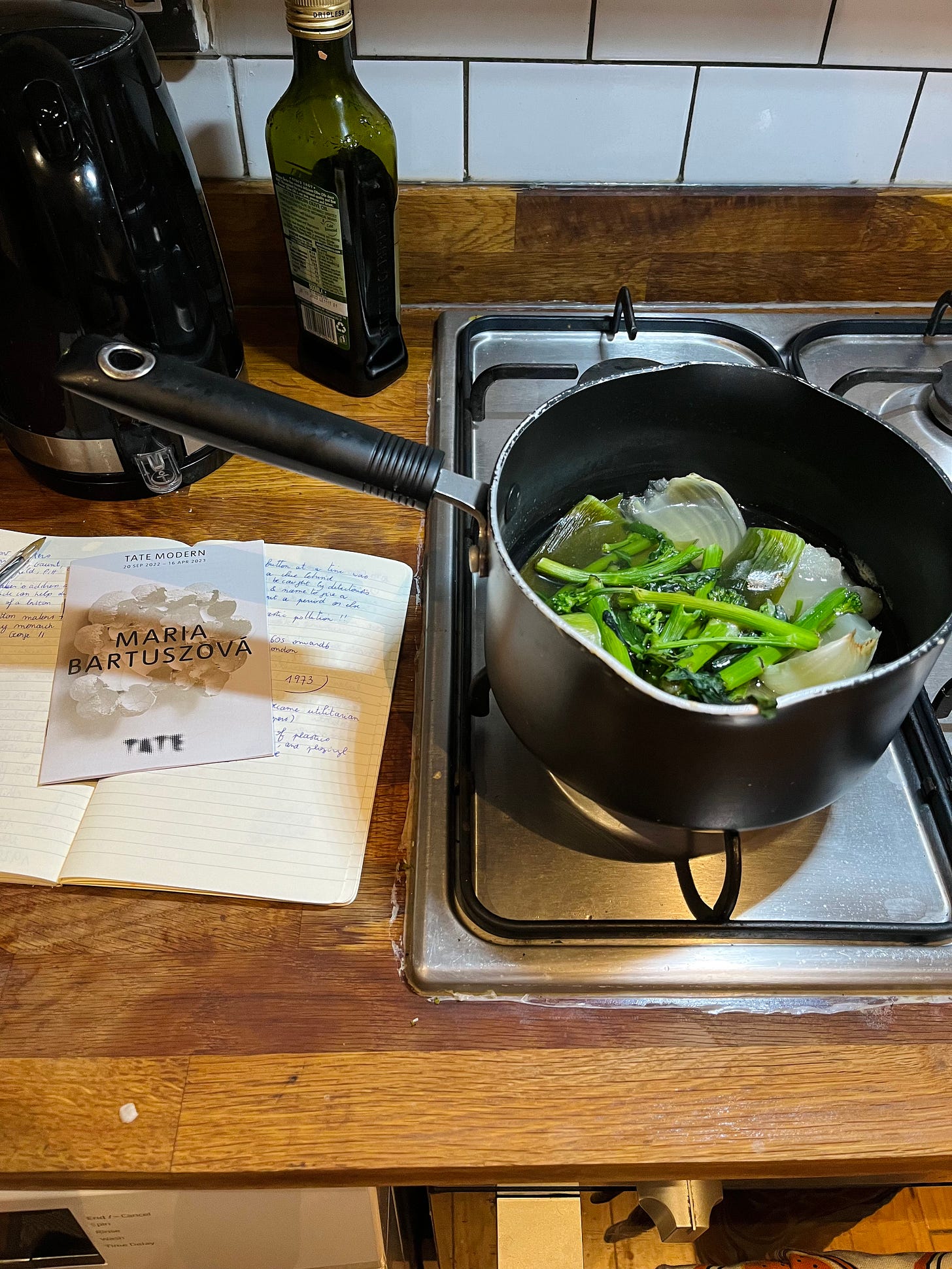

One thing I love to prepare is broth, partly because it requires little attention: no chopping nor timer, exhale. The word ‘broth’ comes from the Germanic root bru which means ‘to prepare by boiling’. Bouillon, bouillir in my native French, to boil. What I call ‘broth hour’ in my kitchen is a time to break-up with the urban pace of modern life, a pot to reuse and enhance. I might be standing in silence, my laptop may be streaming a tv series dangerously close to the gas, it’s a moment when my instinct directs what it is that I want and when.

Bring water to the boil, add vegetable halves and peels, parsley stems and a squeeze of tomato purée. An onion (halved) and two carrots work well too. I love to use the top, green part of a leek (that annoying bit that won’t fit in the fridge, here it goes and finds a new purpose). A pinch of salt if you’re not using any stock cubes, depending on your taste, but the secret ingredient is patience so vegetable scraps and bones can release nutrients.

Last Saturday, I went to Tate Modern. My plan was to go see Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, but after seven years in London I still forget that there are two Tate venues, one on Bankside and the other on Millbank. By the time I had crossed the Millennium Bridge, the woman at the ticket office confirmed that it was too late for me to reach Tate Britain on time. She didn’t comfort me by saying this happens often, but she offered to exchange my ticket for Maria Bartuszová.

‘A tiny void full of a tiny infinite universe.’ – Maria Bartuszová, early 1980s

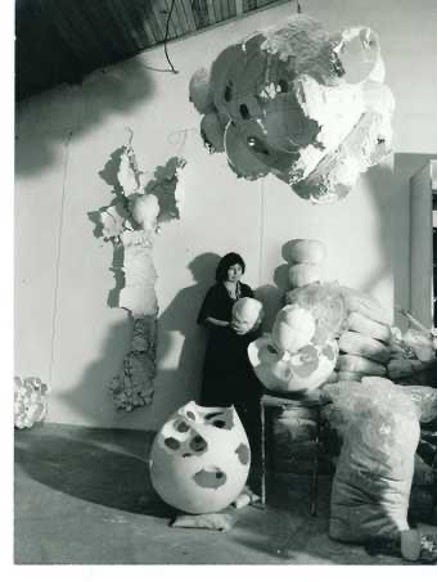

Maria Bartuszová (1926-1996) was a Prague-born sculptor who spent most of her career in the Slovak city of Košice. She was known for her abstract sculptures and her practice was dedicated to exploring relationships between people, nature and form. Her plaster sculptures were a work of casting. In the 1960s and 1970s, she repurposed small rubber balloons and condoms and put them through a mechanic she called ‘gravistimulated shaping’. With the 1980s, Bartuszová moved on to a new practice – ‘pneumatic casting’ – when she blew air into balloons or old car tyres and poured plaster over their surface until they burst. These sculptures were made through movements – a combination of gravity, air pressure and touch – and led to the creation of negative volumes. An explosion: this method shows that destruction doesn’t always mean The End, but can initiate something new – repurposed, regenerated. Bartuszová made ephemeral installations in nature as well.

‘The ropes, strings and hoops that sometimes bind the rounded shapes could be symbolic of human relationships or the constraints that limit the possibilities of living things – the diseases and stresses that undermine what is alive and already restricted by its lifespam.’ – Maria Bartuszová, 1980s

The exhibition moved me. The rooms were mostly monochromatic (except for smaller shapes made with bronze and aluminium), hatching eggs. I was lucky enough to be in the gallery at a quiet time, so I sat in front of Bartuszová’s Untitled, 1986. The abstract form detaches itself from the wall, it snaps with violence, but the texture of the material inspires a certain tenderness – it feels rough and cold and vulnerable, like a cheek in winter. The granulated white colour reminded me of bedsheets after a night's sweat, hard won hours. Listen to the body, take notice of individual cells, it whispered to me.

At the Tate, I read that Bartuszová's work was inspired by intuition, therapy and meditation. She interconnected social and ecological themes as well as science and philosophy through her sculptures. Bartuszová’s craft is sensual – her works don’t hide phantoms behind colours or materials, simple white plasters at first glance, until they unleash before the audience. The art has emotional behaviours as the witness of transformation and the malleability of organisms in specific contexts – and this, precisely, fascinates me about the process of casting. The work is reversed from the one of a writer who fills a white page or a painter who colours canvas – it’s a work of trimming, a process that requires the body to adapt as the mind thinks.

It’s not that I don’t think cooking is relaxing, it’s that I don’t grant myself permission to pause for long enough so cooking wouldn’t be a distraction or a chore that needs to be done so I'm fed. Maria Bartuszová’s methodology reminded me that I can’t rush something I want to give importance to. I find this sentence difficult to write because it seems obvious, yet I choose to forget this often. To keep going can be difficult but look at February passing the baton from winter to spring, regenerating organisms, there is beauty between the start and end lines too – and I’m hanging onto that this week.

Now that you’ve brewed that flavoursome broth, should we make some dinner? This one is a soup to build at your pace and taste, a recipe that goes back and forth between leftovers and newer, seasonal ingredients.

Onion, thinly sliced

Parsley, roughly chopped

Celery, sliced

Leeks, sliced

Courgettes, cubed

Cavolo nero, trimmed and roughly cut

Carrots, sliced

Chestnut mushrooms, thinly sliced

Canned borlotti beans, drained

Tomato purée

In a large pot, fry up the onions, parsley, leeks, celery and carrots with some olive oil. Once the veggies are golden, add the courgettes, cavolo nero and chestnut mushrooms. Gently cook until softened (approx. 10/15 minutes). Add the broth and a squeeze of tomato purée. Simmer. When there are about 10 minutes left before serving time, add the borlotti beans.

I’m generous with the tomato purée because I like it red.

Margaux